This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Observed decrease in Deep Western Boundary Current transport in subpolar North Atlantic” by Koman et al. (2024).

Scientific analysis of the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) off the southern tip of Greenland reveals a 26% decline in transport between 2014 and 2020. This weakening is primarily driven by a freshening signal in the subpolar North Atlantic, which has caused the deep water layers to thin and lose density. While the broader Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) appeared stable during this window, researchers argue this discrepancy stems from how the two systems are measured. By applying a consistent density threshold to the data, the study demonstrates that the AMOC is actually experiencing a statistically significant decrease. Ultimately, the findings suggest that current climate models may need to adopt new observational definitions to accurately track how warming impacts deep-ocean circulation.

A Vital Deep Ocean Current Has Weakened 26%. The Bigger Climate Story Is Hiding in the Definitions.

The Atlantic Ocean is not a static body of water; it is a system in constant, powerful motion. At the heart of this system is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a massive global conveyor belt that transports warm water northward and cold, dense water southward. This circulation is a critical regulator of Earth’s climate system, influencing weather patterns across continents. For this reason, scientists are watching it with intense focus, looking for any signs of change in our warming world.

A recent, comprehensive study has uncovered a surprising and complex shift in one of the AMOC’s most important components. Using six years of continuous data, researchers have been monitoring the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC), the primary southbound artery of this circulation. They found that this vital current has weakened substantially. Yet, paradoxically, the broader AMOC system appears stable. The answer to this puzzle doesn’t just lie in ocean dynamics—it forces a critical re-evaluation of how we define and measure the very systems we are trying to protect.

A Key Deep-Ocean Current Has Weakened Dramatically

The Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) is the main channel that returns cold, dense water from the high latitudes of the North Atlantic back towards the south. Flowing deep beneath the surface along the eastern flank of Greenland, it is the primary component of the AMOC’s lower limb.

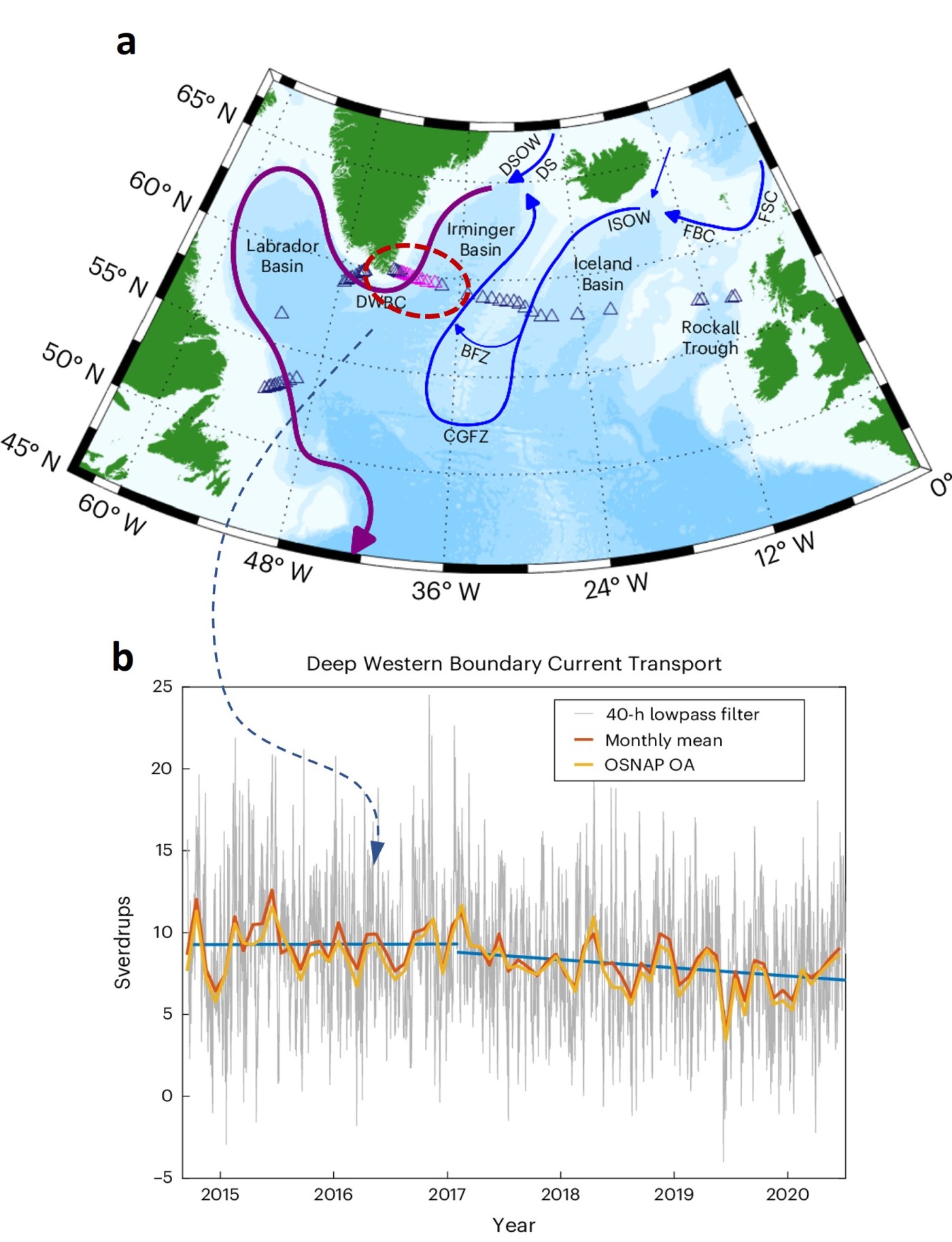

The core finding of the study is striking. Based on continuous monitoring from the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP) between 2014 and 2020, the transport of the DWBC has decreased by a remarkable 26%. This long-term, direct observation confirms a significant change in a foundational piece of the Atlantic circulation.

It’s a Double Blow of “Freshening” and Slowing Velocities

This dramatic decrease isn’t due to a single cause but a combination of two distinct factors that have worked together to weaken the current.

First, the layer of dense water that defines the current has been “thinning,” accounting for 56% of the total decrease. This is the result of an “unprecedented freshening signal”—an influx of less salty, and therefore less dense, water—that began propagating through the region, with its arrival in 2017 coinciding exactly with the start of the current’s decline. As the water becomes lighter, the dense layer that constitutes the current physically shrinks. In some locations, the boundary defining the top of the DWBC has deepened by more than 160 meters.

Second, the current is simply flowing more slowly. The remaining 44% of the transport decrease is due to weakening velocities within the current. This means that not only is the volume of the dense water layer shrinking, but the water that remains is also moving at a slower pace.

The Big Surprise? The Broader Atlantic Circulation Appears Stable

Here lies the central paradox of the study. Even though the DWBC is the “primary component of the lower limb of the AMOC,” direct observations of the overall AMOC have shown it to be “relatively steady” over the exact same period.

This finding is deeply counter-intuitive. It’s like discovering your engine has lost a quarter of its power, but your speedometer still reads a steady 60 mph. How? Because the speedometer isn’t measuring true speed against a fixed definition (like kilometers per hour), but is instead recalibrating its definition of “60 mph” based on the engine’s declining output. It’s masking the problem by changing the measurement itself.

It All Comes Down to How You Define It

The reason for these conflicting trends comes down to a crucial difference in methodology: the DWBC and the AMOC are measured using different benchmarks.

The transport of the DWBC is calculated using a fixed benchmark. Scientists measure the flow of all water that is denser than a constant density level (specifically, an isopycnal of σθ > 27.8 kg m−3). This provides a stable, consistent definition of the current over time.

In contrast, the AMOC is calculated using a flexible benchmark. Its transport is based on a time-varying isopycnal that is recalculated monthly based on where the maximum overturning transport is occurring. As the deep waters have become fresher and less dense, this flexible benchmark has adjusted by lightening its definition. In essence, as the densest layers of the current shrink, the AMOC measurement framework begins to include what was previously considered lighter water as part of its “lower limb,” effectively moving the goalposts and masking the loss of the densest water.

The study revealed a critical “what-if” scenario: if the AMOC were measured using a constant density layer—the same way the DWBC is—it would show a statistically significant decrease. This suggests the apparent stability of the AMOC is an artifact of a shifting definition that is masking the underlying physical changes. As the study’s authors note, this discrepancy is fundamental to how we interpret climate signals.

Finding such notably different trends for two seemingly dependent circulations raises the question of how to best define these transports.

Conclusion: Are We Measuring Change Fast Enough?

This research presents a clear picture: a vital deep ocean current has undergone a significant physical change, driven by both freshening waters and slowing flows. However, this reality is obscured in broader climate metrics because of how we measure them. The very tool used to assess the health of the Atlantic’s circulation—a flexible, time-varying definition—may be masking the symptoms of change.

As our planet continues to transform, this study highlights a new challenge for climate science. It’s not just about deploying moorings and satellites to observe the changes; it’s about pioneering new methods of evaluation that can resolve the fine-grained physical changes—like freshening and thinning—ensuring our definitions keep pace with the planet’s reality.

Figure derived from Figures 1 and 2 in Koman et al. (2024): (a) Schematic of the deep water pathways in the North Atlantic subpolar region. The blue arrows indicate the pathways of the two primary water masses of Norwegian Sea Water origin (ISOW and DSOW), and the purple pathway depicts the DWBC (after the two water masses merge). All mooring locations in the OSNAP programme are denoted by triangles, with the moorings used in this study to determine the DWBC in magenta. Bathymetry colours change with every 1,000 m in depth. DS, Denmark Strait; ISOW, Iceland Scotland overflow water; FBC, Faroe Bank Channel; FSC, Faroe Shetland Channel; BFZ, Bight Fracture Zone; CGFZ, Charlie Gibbs Fracture Zone. (b) A 40-h lowpass-filtered time series of the DWBC transport (grey) overlaid with the monthly mean (red), the monthly mean from the OSNAP objective analysis (OSNAP OA, yellow) and the linear trends for August 2014 to January 2016 and February 2016 to July 2020 (blue).

Koman, G., Bower, A.S., Holliday, N.P. et al. Observed decrease in Deep Western Boundary Current transport in subpolar North Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1148–1153 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01555-6

Leave a comment