This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Strengthening of Labrador Sea Overturning Linked to Subsurface Freshening Over Recent Decades” by Li et al. (2026).

Introduction: The Ocean’s Engine and a Long-Standing Puzzle

The Atlantic Ocean is home to a vast, powerful system of currents often called the “ocean’s great conveyor belt.” Known to scientists as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), this network transports heat around the globe, playing a critical role in regulating the global climate system. One of the key “engine rooms” for this circulation is the Labrador Sea, a basin between Greenland and Canada where warm waters cool, sink, and begin their journey south.

For decades, this particular engine room has puzzled scientists. Direct observations historically showed its contribution to the great conveyor belt to be surprisingly weak and stable. But recent discoveries have turned this understanding on its head, revealing that this circulation is not only changing but strengthening—due to a surprising and counter-intuitive cause.

1. The Old Story: A Perfectly Balanced Act Kept Things Stable

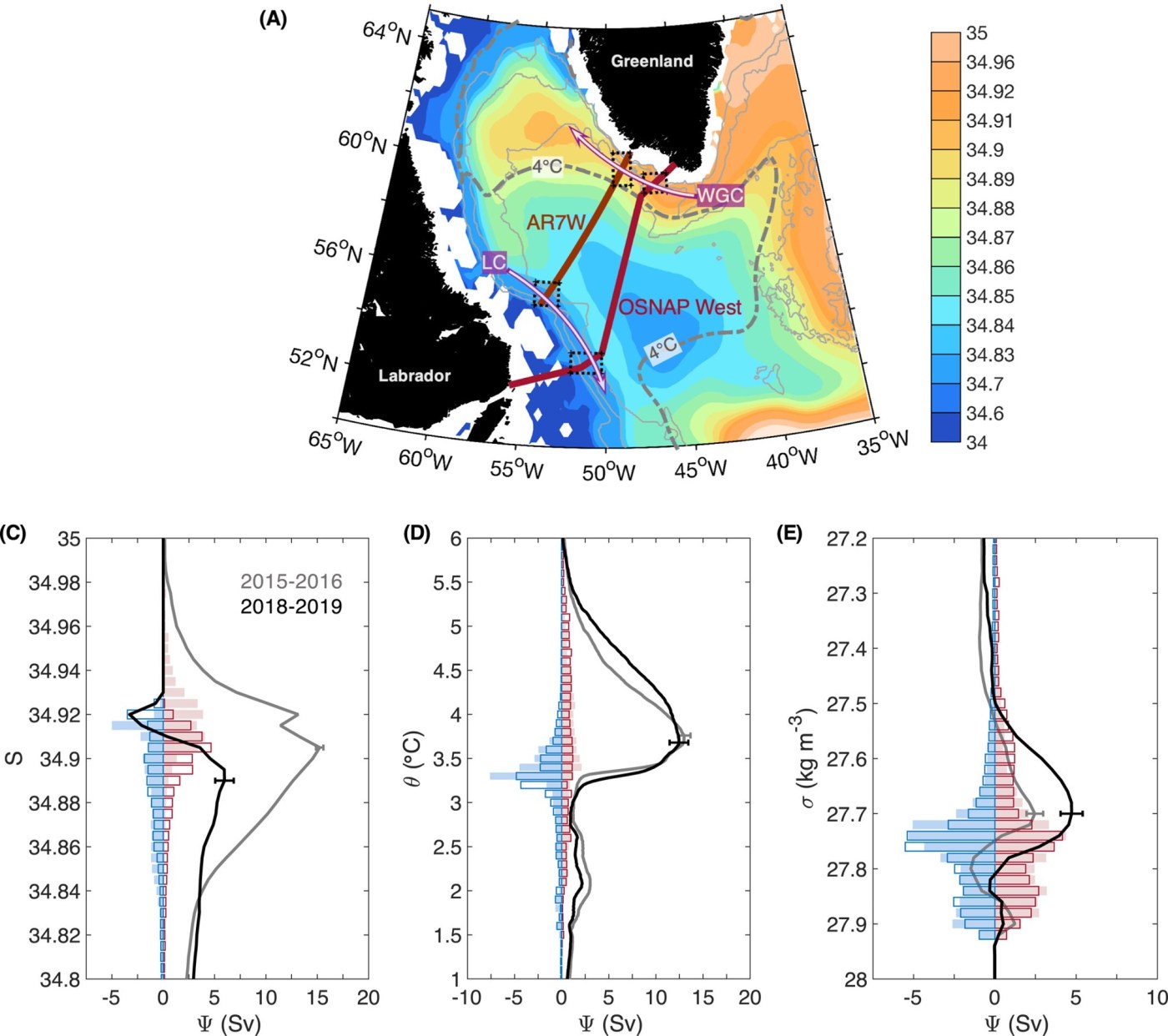

The long-standing explanation for the Labrador Sea’s weak circulation was a phenomenon called “density compensation.” In simple terms, as warm, salty water flowed into the sea via the West Greenland Current (WGC), it underwent a transformation, becoming colder and fresher before flowing out as part of the Labrador Current (LC).

These two changes had opposing effects on the water’s density. Cooling makes water denser and heavier, causing it to sink. But freshening—reducing the salt content—makes water less dense and lighter. In the Labrador Sea, these two forces largely canceled each other out. This balancing act resulted in a minimal change in the overall water density, which in turn led to a consistently weak overturning circulation in the region.

2. The Plot Twist: A Sudden and Significant Strengthening

Recent observations have revealed a dramatic shift in this long-standing pattern. Data collected from the mid-to-late 2010s shows that the historically weak circulation in the Labrador Sea has undergone a sudden and significant strengthening.

According to the research, the Labrador Sea overturning circulation strengthened by approximately 50% from the 2014–2016 period to the 2018–2020 period. For oceanographers, a change of this magnitude in such a critical component of the climate system is a major finding, signaling that fundamental dynamics in the North Atlantic are in flux.

3. The Unlikely Suspect: Fresher Water Flowing Beneath the Surface

The primary driver of this strengthening is an influx of fresher, less salty water—a completely counter-intuitive cause. Many climate models predict that large-scale freshening, particularly at the ocean’s surface, should weaken overturning circulation by making it harder for water to become dense enough to sink.

However, the new research reveals a different mechanism at play. The change is not happening at the surface but in the subsurface waters flowing into the Labrador Sea via the West Greenland Current. This inflowing water became significantly fresher and therefore lighter (less dense). Because its temperature didn’t change much, this freshening dramatically increased the density difference between the now-lighter inflowing water of the West Greenland Current and the colder, denser outflowing water of the Labrador Current. This amplified density gradient between the basin’s entry and exit points is what strengthened the overturning circulation.

In a surprising twist, it wasn’t saltier water that invigorated the current, but fresher water. By making the incoming flow lighter, it created a steeper density gradient that effectively boosted the strength of the entire circulatory system.

4. Why Location Is Everything: The Nuance of Ocean Freshening

This discovery highlights a subtle but critical point: the impact of freshwater on ocean circulation depends critically on its location and depth.

While many theories correctly focus on how freshening at the ocean’s surface can suppress deep water formation and weaken circulation, this real-world data shows the opposite can be true. When freshening occurs in the subsurface waters of a boundary current flowing into a basin, it can actually enhance the density gradients that power the circulation, strengthening it. This discovery underscores the immense complexity of the ocean system and reinforces why continuous, direct observation is essential for accurately understanding how our climate is changing.

Conclusion: A More Dynamic System Than We Knew

The long-held view of a weak, stable, and density-compensated overturning circulation in the Labrador Sea is now outdated. We now have clear evidence that this system is dynamic and has recently strengthened, driven paradoxically by an influx of fresh water beneath the surface.

This leaves scientists with a critical question: As the Arctic continues to change and send more freshwater south, will this surprising strengthening effect continue, or is the Atlantic’s circulation system heading toward another, unknown tipping point?

Figure derived from Figures 1 & 3 in Li et al. (2026): (a) Mean salinity (color shading) and temperature (gray dashed contour) fields at the subsurface Labrador Sea (200–500 m) from World Ocean Atlas 2018, superimposed by the location of the AR7W and OSNAP West sections. Gray thin lines are the 1,000 m-, 2,000 m-, and 3,000 m-isobaths. The inflowing and outflowing boundary currents are labeled with white arrows. WGC, West Greenland Current; LC, Labrador Current. Black dotted boxes on the sections indicate where EN4 profile data are collected for the analysis. (c) Mean volume transport profiles in salinity space (at intervals of 0.002). Transport of the inflowing/outflowing waters is indicated by red/blue bars (filled, 2015–2016; open, 2018–2019). The mean streamfunction (transport accumulated from high to low salinities) is indicated by solid lines, with the horizontal bar for uncertainty in the maximum transformation (plus/minus one standard error based on the monthly values). Panels (d, e) Similar to panel (c) but for transports in potential temperature, and potential density coordinates, respectively. For illustration purpose, the temperature interval is 0.1℃ in panel (d) and the density interval is 0.02 kg m−3 in panel (e).

Li, F., Fu, Y., Petit, T., & Zou, S. (2026). Strengthening of Labrador Sea overturning linked to subsurface freshening over recent decades. Geophysical Research Letters, 53, e2025GL118605. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL118605

Leave a comment