This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Reduced cooling in the Norwegian Atlantic Slope Current: investigating mechanisms of change from 30 years of observations” by Baumann et al. (2025).

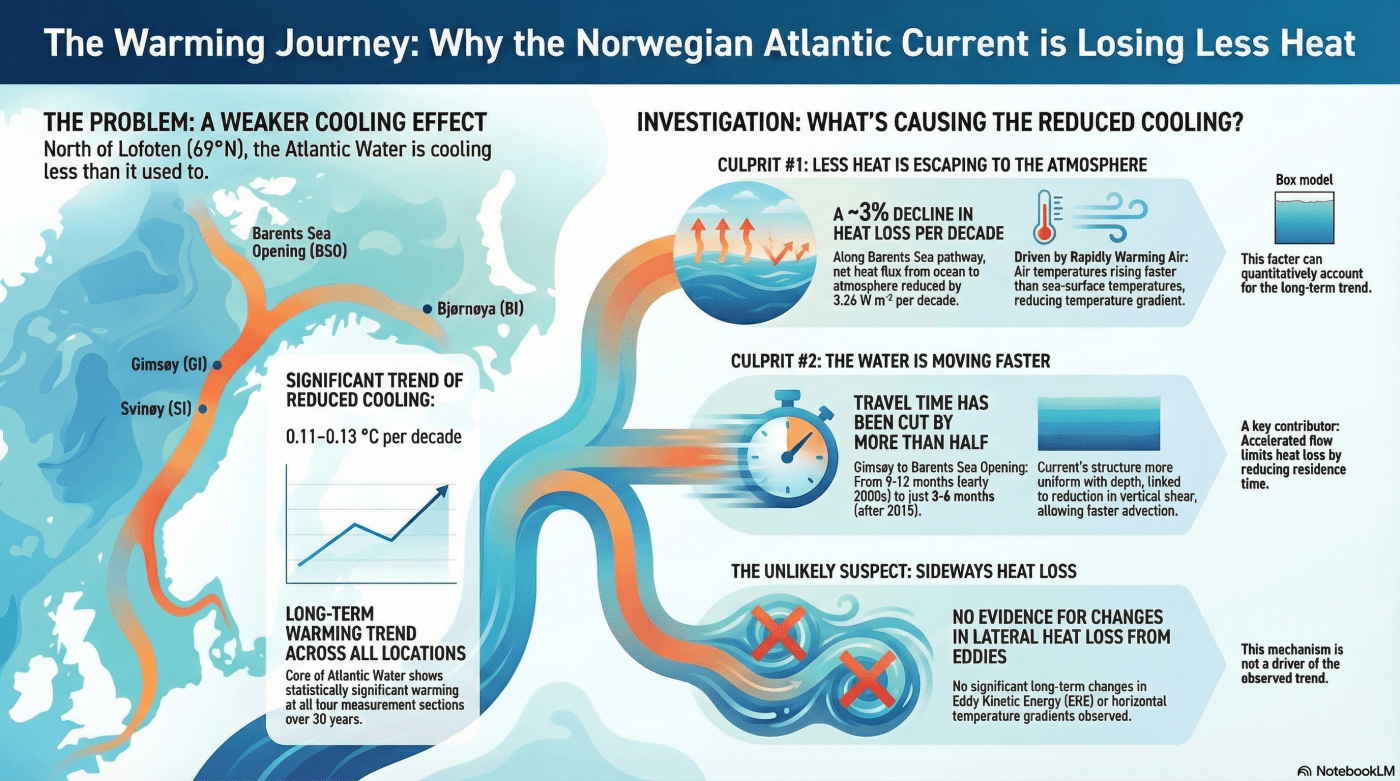

This research analyzes thirty years of hydrographic data to investigate why Atlantic Water in the Norwegian Atlantic Slope Current is cooling less as it travels toward the Arctic. Using observations from 1993 to 2022, the authors identify a significant warming trend north of the Lofoten Islands, where the rate of cooling has dropped by over 0.10°C per decade. The study evaluates three potential causes for this change: atmospheric heat exchange, lateral eddy activity, and current speed. While eddy-driven heat loss shows no significant change, the authors find that reduced air-sea heat fluxes and faster advection speeds are the primary drivers. Specifically, a shift toward a more barotropic current appears to move water faster, leaving less time for the atmosphere to chill the passing current. Ultimately, these findings suggest a northward amplification of warming along a critical path of the global ocean circulation.

The North Atlantic hosts one of Earth’s great climate engines, a massive current of warm water that functions as a thermostat for Northern Europe. This powerful flow, the Norwegian Atlantic Current, is a critical highway, carrying immense volumes of heat from the subtropics on a long journey poleward. This warmth is what keeps the high latitudes habitable, a gift from a distant ocean.

But this current performs another, equally vital function. As it travels north through the Nordic Seas, it releases its heat into the colder atmosphere, transforming the water itself. This cooling process makes the water denser, allowing it to eventually sink and begin its return journey south in the deep ocean, driving a global circulation system that shapes weather patterns worldwide. For this planetary engine to run smoothly, this cooling must be efficient.

Now, a comprehensive analysis of 30 years of observational data has uncovered a worrying change in this fundamental process. Researchers have found that this essential cooling mechanism is weakening. The northbound water is not shedding its heat as effectively as it used to, disrupting a delicate balance that has existed for millennia and raising new questions about the future of the Arctic.

The Atlantic water flowing north isn’t cooling down as much as it used to.

The central finding of the new study, based on data collected between 1993 and 2022, is unambiguous. The study shows that north of the Lofoten Islands, the Atlantic Water in the current is failing to cool as much as it used to.

Specifically, the study quantifies this change as a reduction in cooling at a rate of 0.11 to 0.13 °C per decade. While a fraction of a degree per decade sounds small, when applied to the immense volume of water in this current, it represents a monumental shift in the planet’s heat budget—a persistent fever in a vital artery of the global circulatory system. The clear implication is that warmer water is now being transported further north than in previous decades. The study’s authors call this a “northward amplification of AW warming,” meaning the heat that used to be released along the way is now being pushed deeper into the Arctic gateway.

A warmer atmosphere is preventing the ocean from releasing its heat.

The primary reason for the reduced cooling, as identified by the researchers, is a change in the exchange of heat between the sea and the air. Think of this process as the ocean “breathing out” heat into the colder atmosphere above it. For this to happen efficiently, there needs to be a significant temperature difference between the warmer water and the colder air.

Over the last three decades, this heat exchange has become less effective because air temperatures over the Nordic Seas have been rising even faster than sea-surface temperatures. This warming atmosphere acts like an insulating blanket, making it harder for the ocean to release its thermal energy. The study quantifies this effect, showing that the net heat flux from the ocean to the atmosphere has decreased by about 3% per decade along the current’s path. This is driven overwhelmingly by a reduction in what is known as sensible heat flux—the direct transfer of heat from the warm ocean to the colder air—which accounts for the vast majority of the net decrease.

The water is speeding through its ‘cooling zone’ much quicker than before.

In a counter-intuitive twist, the researchers found another contributing factor: the water is moving faster. While the total volume of water being transported by the current hasn’t changed, the speed at which water properties travel has increased dramatically.

To uncover this, scientists tracked the movement of salinity anomalies—distinct pockets of saltier or fresher water—as they propagated along the current. They found that the travel time for water moving from the Gimsøy section to the Barents Sea Opening has been cut drastically. In the early 2000s, this journey took an average of 9–12 months; after 2015, the same trip took just 3–6 months. This acceleration appears linked to a change in the current’s internal structure, making the flow more uniform from top to bottom and allowing anomalies to propagate northward more efficiently. This means the warm Atlantic water is not only insulated by a warmer atmospheric blanket, but it’s also racing under that blanket so quickly that it has even less opportunity to shed its heat before reaching the Arctic.

A Warmer Future for the Arctic?

The 30-year record reveals a complex and dynamic shift in a fundamental climate process. The Norwegian Atlantic Current is losing its ability to cool efficiently, but the cause isn’t a single, simple fault. Instead, it is a dynamic interplay between two powerful forces: the “warm blanket” of the atmosphere and the “faster highway” of the current itself. The researchers also investigated other potential causes, such as changes in ocean eddies that mix heat laterally, but found no evidence that they were responsible for the observed trend.

This study reveals that the two drivers do not act in constant lockstep; their influence waxes and wanes over time. In some periods, such as from 1995–2000 and 2005–2015, the variability in atmospheric warming and its insulating effect appears to be the dominant factor. In other years, like the early 2000s and after 2017, the atmospheric blanket alone cannot explain the changes, pointing to the current’s acceleration as the key mechanism at play. This is not just a system with a simple problem, but a complex engine whose components are failing in different ways at different times. As this amplified warming continues its relentless push into the Arctic, what will it mean for the future of sea ice, polar ecosystems, and the stability of the global climate system?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Baumann, T. M., Skagseth, Ø., Ingvaldsen, R. B., and Mork, K. A.: Reduced cooling in the Norwegian Atlantic Slope Current: investigating mechanisms of change from 30 years of observations. Ocean Sci., 22, 17–29, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-22-17-2026, 2026.

Leave a comment