This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Future strengthening of the Nordic Seas overturning circulation” by Årthun et al. (2023).

When we talk about climate change and the ocean, one of the most prominent stories is the weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This vast system of currents, often called the ocean’s “great conveyor belt,” transports heat around the globe and is a critical regulator of our climate. The widely accepted projection is that this vital circulation will slow down throughout the 21st century.

However, a fascinating 2023 study by Marius Årthun and colleagues has uncovered a surprising and counter-intuitive twist in this narrative. By analyzing a suite of global climate models, they found that while the broader AMOC is expected to weaken, a key component of this system—the overturning circulation in the Nordic Seas—is actually projected to rebound and strengthen in the latter half of this century.

This research reveals that the story of our planet’s ocean circulation is far more complex than a simple tale of decline. This post will break down the key takeaways from this pivotal study.

A Surprising Rebound in the Nordic Seas

Climate models project that the overturning circulation in the Nordic Seas will follow a distinct V-shaped pattern this century. To understand this, we need to look at two different ways of measuring it. One, MOCz, measures overturning in physical depth, like watching an elevator go up and down. The other, MOCσ, measures it in “density space,” which is like tracking the net number of people who get off the warm, crowded ground floor and arrive at the cold, empty top floor, regardless of which elevator they took. The study notes that MOCσ “best quantifies” the actual transformation of warm Atlantic water into the cold, dense water that powers the deep ocean.

The models show that while the elevator traffic (MOCz) is projected to steadily decline all century, the net transport of water to its densest state (MOCσ) tells a different story. This more crucial metric is expected to decline until about the 2040s and then begin to increase again, recovering toward present-day levels by the year 2100. This divergence highlights a crucial nuance: not all parts of the system are responding to climate change in the same way.

It’s Driven by Horizontal Flow, Not Deep Sinking

The study pinpoints the driver of this rebound not as more water getting cold and sinking in the open ocean—the traditional picture of how the “conveyor belt” works—but as an intensification of horizontal currents. Specifically, the study reveals the cause is a stronger cyclonic (counter-clockwise) gyre within the Nordic Seas. This finding, the authors state, “challenge[s] the importance of open-ocean deep convection in setting the strength of the AMOC.”

The researchers found a strong correlation (r = 0.76) between a more vigorous horizontal gyre and a strengthened overturning circulation. The mechanism is rooted in the ocean’s density structure. The study found an extremely high correlation (r = 0.91) between the overturning strength and the zonal (west-east) density gradient, confirming this link. The paper also confirmed that changes in wind stress over the region were negligible, ruling them out as a primary driver.

The Ultimate Driver is a Large-Scale Atlantic Pattern

The changes in the Nordic Seas are not isolated events but are instead linked to much larger patterns of temperature and density across the entire Atlantic Ocean. The study suggests a clear causal chain: large-scale temperature patterns in the Atlantic are advected, or carried by currents, north into the Nordic Seas. There, they alter the local density structure, which in turn strengthens the horizontal gyre.

Specifically, the study identified a strong connection to the Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV), a natural, long-term cycle of warming and cooling in the North Atlantic. In the CESM-LE climate model, the temporal pattern of the AMV closely matches the weakening and subsequent strengthening of the Nordic Seas circulation, with a strong correlation of r = 0.65. This link was also found across a suite of CMIP6 models, which showed a multi-model mean correlation of 0.64, suggesting this is a robust physical connection.

A Stronger Nordic Current Could Be a Stabilizing Force

The overturning circulation in the Nordic Seas is a critical headwater for the entire AMOC. It is where warm Atlantic waters are transformed into the cold, dense “overflow waters” that spill over undersea ridges and form the deep, southward-flowing limb of the conveyor belt.

The study found that the strengthened horizontal circulation has a tangible effect on these overflows, primarily the one passing through the Faroe-Shetland Channel (with a correlation of 0.56), while showing no significant relationship with the Denmark Strait overflow. This reinforced circulation has a detectable impact downstream, influencing the overturning in the eastern subpolar North Atlantic at depths of approximately 1500–2000 meters—a region dominated by this Iceland-Scotland Overflow Water. The correlation between the Nordic Seas overturning and the subpolar overturning at 2000 meters is r = 0.46, quantifying this significant link. This leads to the study’s most powerful conclusion: this regional strengthening could act as a stabilizing factor, potentially reducing the magnitude of the decline expected for the broader AMOC.

“A strengthened Nordic Seas overturning circulation could therefore be a stabilizing factor in the future AMOC.”

A More Complex Climate Picture

The findings from this study fundamentally complicate the straightforward narrative of a uniformly weakening Atlantic ocean circulation. The research provides compelling evidence that the ocean’s response to climate change is a mosaic of complex, regionally varied changes, not a monolithic global trend.

By showing that the Nordic Seas overturning is projected to strengthen, the study highlights a potential source of resilience within the climate system. However, the authors add a layer of scientific caution, noting that current global climate models have relatively coarse resolutions and may not perfectly capture processes along narrow boundary currents. They state that these findings should be evaluated in new, high-resolution models to confirm the results.

This discovery complicates the simple story of a collapsing ocean current, but what other surprising feedback loops might our changing climate have in store?

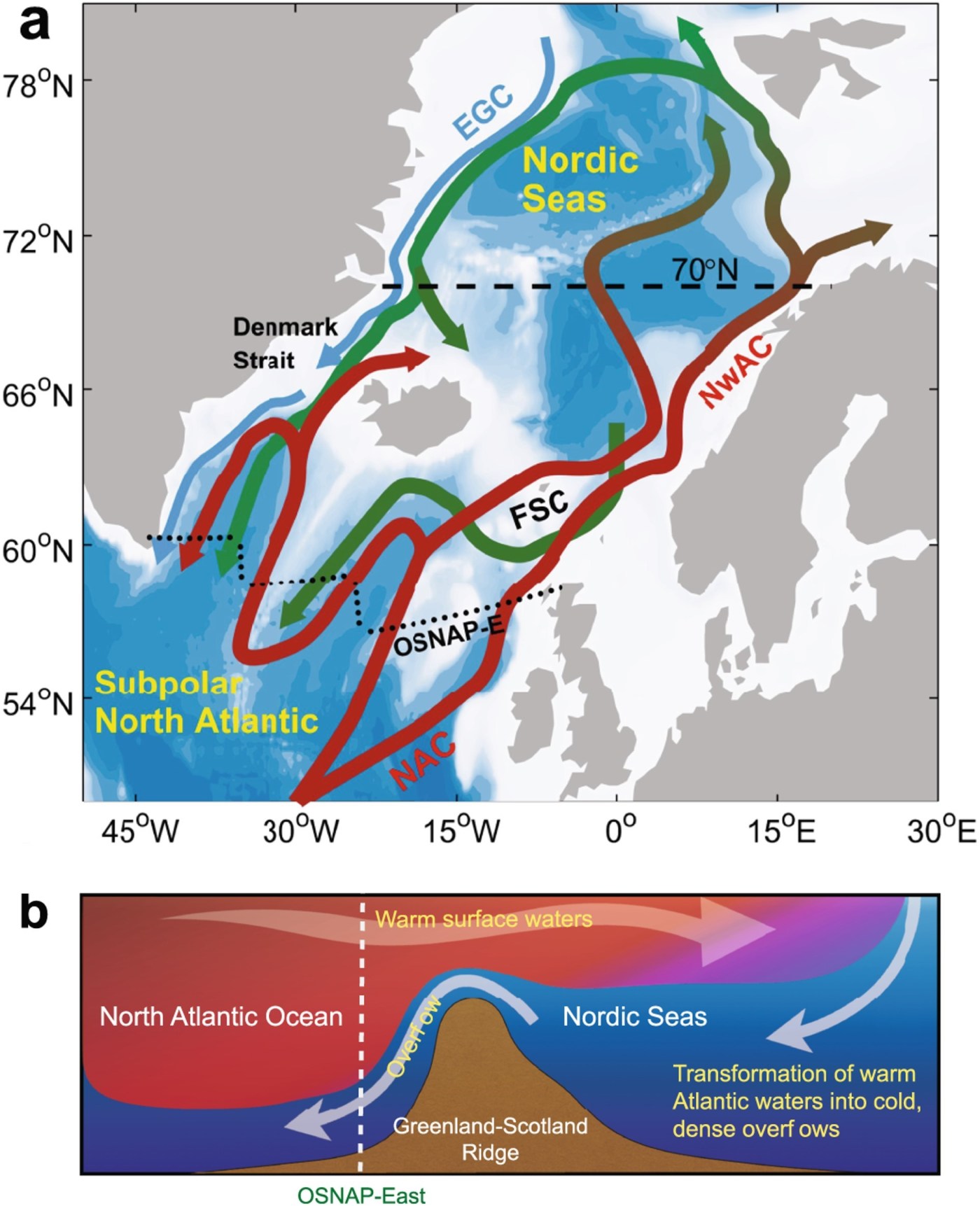

Figure 1 from Årthun et al. Ocean circulation of the eastern subpolar North Atlantic Ocean and

Nordic Seas. a Schematic of the major ocean currents crossing the Greenland-Scotland Ridge (GSR). The arrows represent the pathways and transformation of warm Atlantic waters (red arrows) in the NAC-NwAC to cold, dense overflows (green arrows) that exit the Nordic Seas through the Denmark Strait and Faroe-Shetland Channel (FSC). The cold, fresh East Greenland Current (EGC) is shown by blue arrows. The sections at 70°N and in the eastern subpolar North Atlantic (mimicking the eastern part of the array from the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program; OSNAP-East) used to calculate overturning circulation are shown as dashed black lines. NAC: North Atlantic Current, NwAC: Norwegian Atlantic Current. b Schematic representation of the meridional flow across the GSR highlighting how the dense overflow waters from the Nordic Seas contribute to the lower limb of the overturning circulation at OSNAP-East.

Årthun, M., Asbjørnsen, H., Chafik, L. et al. Future strengthening of the Nordic Seas overturning circulation. Nat Commun 14, 2065 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37846-6

Leave a comment