This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Equatorial upwelling of phosphorus drives Atlantic N2 fixation and Sargassum blooms” by Jung et al. (2025).

Deep Dive Podcast “Climate History Solves Sargassum Crisis”:

Introduction: The Golden Tide Mystery

Since 2011, a mysterious phenomenon has plagued the coastlines of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and tropical Atlantic. Massive, sprawling mats of golden-brown Sargassum seaweed have been washing ashore in unprecedented quantities. In the open ocean, this floating golden forest is a vital ecosystem, providing critical habitat and food for tuna, turtles, and seabirds. The problem begins when this natural wonder grows to an extreme scale and drifts ashore, blanketing pristine beaches in a thick, decaying carpet. For coastal communities, these events are a recurring nightmare. The decomposing seaweed releases hydrogen sulfide gas, creating a foul odor, disrupting tourism, and posing genuine health risks to residents.

This deluge originates from a vast, floating ecosystem that appeared seemingly out of nowhere: the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. It has since grown to become the largest interconnected biome of its kind on Earth, a scientific puzzle that has baffled researchers for over a decade. For years, many have pointed to the usual suspects, such as nutrient pollution from major rivers or warming ocean waters, as the fuel for these explosive blooms.

However, groundbreaking new research published in Nature Geoscience reveals a far more complex and surprising story. The real driver isn’t what’s happening along the coasts, but rather a powerful, natural engine operating in the deep, open ocean, modulated by massive climate cycles. Here are the five key takeaways from the study that are rewriting our understanding of this global problem.

1. It’s not caused by river pollution.

A leading theory for the dramatic increase in Sargassum blamed nutrient runoff from major South American rivers, particularly the Amazon and the Orinoco. The logic seemed straightforward: as these rivers discharged nutrient-rich water into the Atlantic, they were providing a feast for the floating seaweed.

This new study comprehensively debunks that idea. After analyzing years of data, researchers found no significant interannual relationship between the size of the Sargassum blooms and the amount of discharge from these rivers. While river outflows might play a role in localized blooms close to shore, they are not the primary driver of the massive, basin-wide phenomenon. This is a crucial and counter-intuitive finding. It tells us that looking for the solution in coastal pollution policies alone is like searching for keys under a lamppost—the real action is happening hundreds of miles offshore in the vast, deep ocean, driven by forces far larger than any single river.

2. The true fuel source comes from the deep ocean, powered by climate cycles.

If not rivers, then what is feeding the seaweed? The answer lies in a natural process called “equatorial Atlantic upwelling,” where deep, cold, nutrient-rich water is brought to the sunlit surface. The study found that this upwelled water is uniquely loaded with what scientists call “excess phosphorus”—meaning it contains far more phosphorus than nitrogen. It’s the oceanic equivalent of a fertilizer mix that’s all “Bloom Booster” (phosphorus) but has almost no “Green Growth” formula (nitrogen).

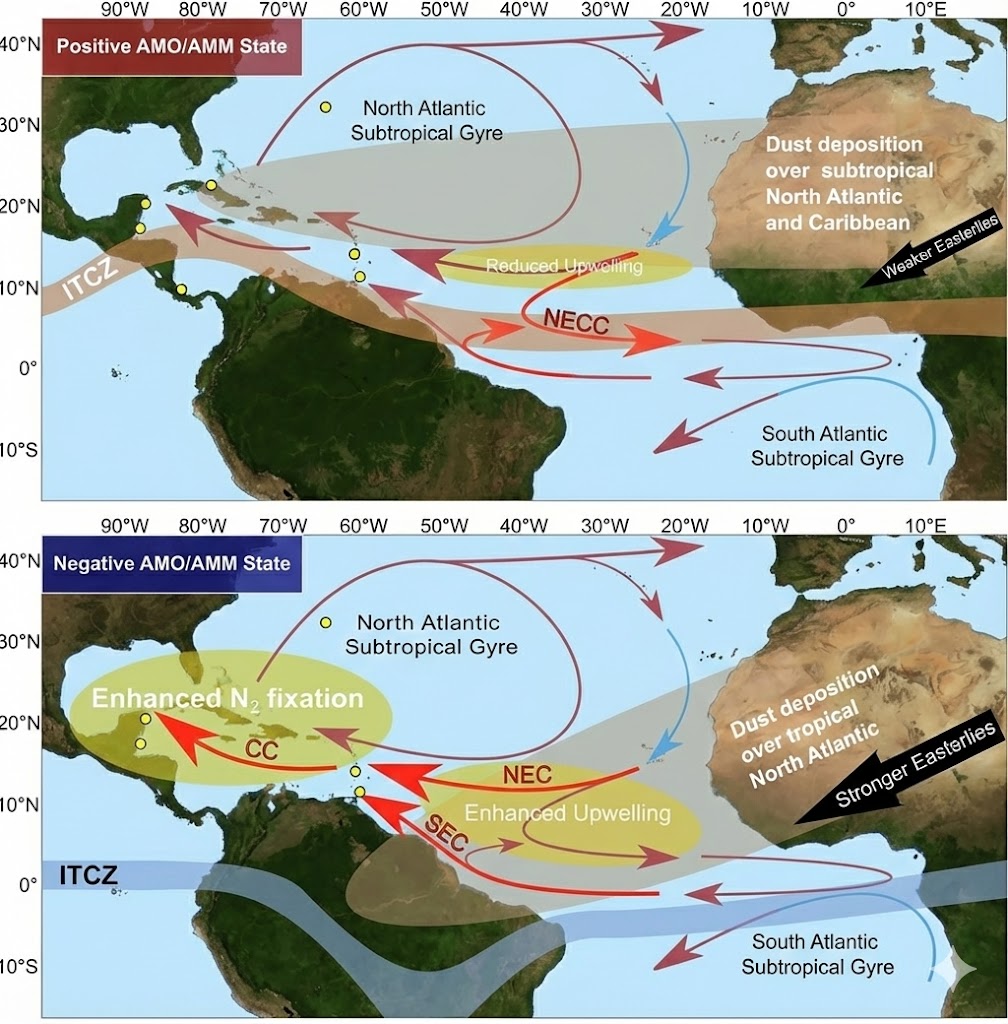

This upwelling isn’t constant; its intensity is controlled by vast, cyclical climate patterns known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) and the Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM)—think of these as the Atlantic’s long-term and short-term climate heartbeats. During the “negative phases” of these cycles, trade winds across the Atlantic strengthen. These powerful winds act like a giant pump, intensifying the upwelling and delivering a massive feast of phosphorus from the deep ocean to the surface, right where the Sargassum lives. But this phosphorus-rich feast comes with a catch: the surface waters are starved of the other essential ingredient for life, nitrogen. This would be a deal-breaker for most organisms, but as the next finding reveals, Sargassum has a solution.

3. Sargassum has a superpower: it partners with its own fertilizer factories.

To grow, Sargassum needs both phosphorus and nitrogen. While the deep-ocean upwelling provides an abundance of phosphorus, the surface waters of the tropical Atlantic are often poor in usable nitrogen. This is where the seaweed’s secret weapon comes into play.

Sargassum hosts colonies of specialized microbes on its surface known as epiphytic N2-fixing bacteria. In a classic example of a mutualistic relationship, these bacteria pull nitrogen gas directly from the atmosphere and convert it into a usable form of fertilizer, which they provide directly to their seaweed host, likely in exchange for phosphorus and a place to live. This biological partnership is a game-changing competitive advantage. It allows Sargassum to essentially create its own nitrogen fertilizer, enabling it to thrive in phosphorus-rich waters where other organisms might struggle. This unique ability to create its own fertilizer makes Sargassum perfectly adapted to thrive in the phosphorus-rich waters of the equatorial Atlantic. The only thing missing was the seaweed itself. For decades, the engine was running, but the key wasn’t in the ignition—until a chance event changed everything.

4. The problem started when Sargassum was pushed into this fertile zone.

The conditions for massive blooms—the powerful, phosphorus-rich upwelling—have existed in the equatorial Atlantic for a very long time, long before the first major inundations in 2011. So what changed? The seaweed itself wasn’t in the right place at the right time.

The study posits that the crisis was triggered around 2010 when exceptionally strong westerly winds likely caused a massive export of Sargassum from its historical home in the Sargasso Sea (a region in the North Atlantic) into the tropical Atlantic. This event pushed a large seed population of the seaweed into the phosphorus-rich fertile zone for the first time. Once there, powered by deep-ocean nutrients and its nitrogen-fixing sidekicks, the seaweed population exploded, giving birth to the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt.

5. This discovery gives us a new tool for prediction.

By identifying the true drivers of the blooms, the research provides a powerful new tool for forecasting them. The study found a strong correlation between the negative phases of the Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM), increased nitrogen fixation, and the largest Sargassum blooms.

The direct implication is that the state of the AMM can now be used to better predict the annual severity of Sargassum events. This isn’t just an academic exercise. For coastal communities, predicting a severe Sargassum season months in advance means the difference between economic disaster and resilience. It allows them to pre-allocate cleanup funds, warn tourism operators, and prepare public health resources before the golden tide even appears on the horizon.

Conclusion: A New Perspective on a Global Problem

The mystery of the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is not a simple story of coastal pollution. Instead, it is a fascinating and complex interplay between large-scale oceanography, powerful climate patterns, and the unique biology of the seaweed itself. It is a natural phenomenon, born from the seaweed’s journey into a fertile, phosphorus-rich zone, where its ability to partner with nitrogen-fixing microbes gave it the ultimate competitive edge.

This new understanding shifts our perspective, but it also raises an urgent question for the future. The future of Sargassum will depend on how global warming affects these vast ocean and climate systems. As our planet changes, will these natural cycles intensify, turning a seasonal nuisance into a permanent crisis for our coastlines?

Figure modified from extended data Fig. 5 in Jung et al. (2025): Schematic overview of the ITCZ position, the Saharan dust plume, and surface currents during positive (top) and negative (bottom) AMO/Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM) phases. Positive AMO/AMM phases correspond to a northward displacement of the ITCZ, a predominance of the Saharan dust plume over the subtropical North Atlantic and Caribbean, reduced easterly wind strength, and an enhanced North Equatorial Counter Current (NECC). Negative AMO/AMM phases correspond to a southward displacement of the ITCZ, a predominance of Saharan dust over the equatorial North Atlantic and Amazon basin, and stronger easterlies that enhance equatorial upwelling. Also, during negative AMO/AMM phases the North Equatorial Current (NEC), the South Equatorial Current (SEC) and the Caribbean Current (CC) are stronger and transport more Atlantic water with excess P into the Caribbean, ultimately enhancing N2 fixation. Base map: ‘Blue Marble’ global mosaic. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Jung, J., Duprey, N.N., Foreman, A.D. et al. Equatorial upwelling of phosphorus drives Atlantic N2 fixation and Sargassum blooms. Nat. Geosci. 18, 1259–1265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01812-2′

I enjoyed reading this paper. But, the actual equatorial upwelling in the Atlantic takes place in the eastern equatorial region of 3S – 3N. So, technically, “equatorial upwelling” in this study should be called off-equatorial upwelling, which appears to be located around 10N. I am not really sure if 10N is an upwelling zone.

Greg Foltz commented:

There’s upwellling in the Guinea Dome in the east, otherwise I think it would have to be wind-induced mixing and deepening of the mixed layer, not so much upwelling.