As the surface ocean warms and polar ice sheets melt due to increasing anthropogenic greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, near-surface ocean stratification is increasing almost everywhere. In tropical and subtropical oceans, in particular, enhanced near-surface stratification inhibits the mixing between warmer surface water and cooler subsurface water, leading to a shallower surface mixed layer. In the spring and summer seasons, heating from the sea surface has to be stored in a shallower mixed layer. This means that sea surface temperature (SST) has to increase to compensate for the smaller heat container:

ΔSST = QNET/(DMIX+ΔDMIX) – QNET/DMIX.

Here QNET is the net surface heat flux, DMIX is the surface mixed layer depth. Assuming that |ΔDMIX/DMIX|≪1, we can use a binomial expansion to simplify this equation to

ΔSST ~ -ΔDMIX/DMIX × QNET.

Note that since ΔDMIX < 0 and QNET > 0, ΔSST has to be always positive (i.e., SST warming).

During fall and winter, on the other hand, cooling from the sea surface will have to empty out the extra heat stored during spring and summer. So, ΔSST (< 0) should be intensified as well. The net impact is an intensification of the seasonal cycle in SST.

A good analogy is to compare two coffee pots, one with 1 liter of water and the other with only 0.1 liter of water. Under the same heating rate, the latter will heat faster and stronger. Note that the same idea can be applied to interannual SST variability driven by surface heat flux anomalies. It is also important to note that increased SST variability is linked to increased frequency of extreme weather events.

See Li et al. (2020), Jo et al. (2022), and Liu et al. (2024) for more on this topic.

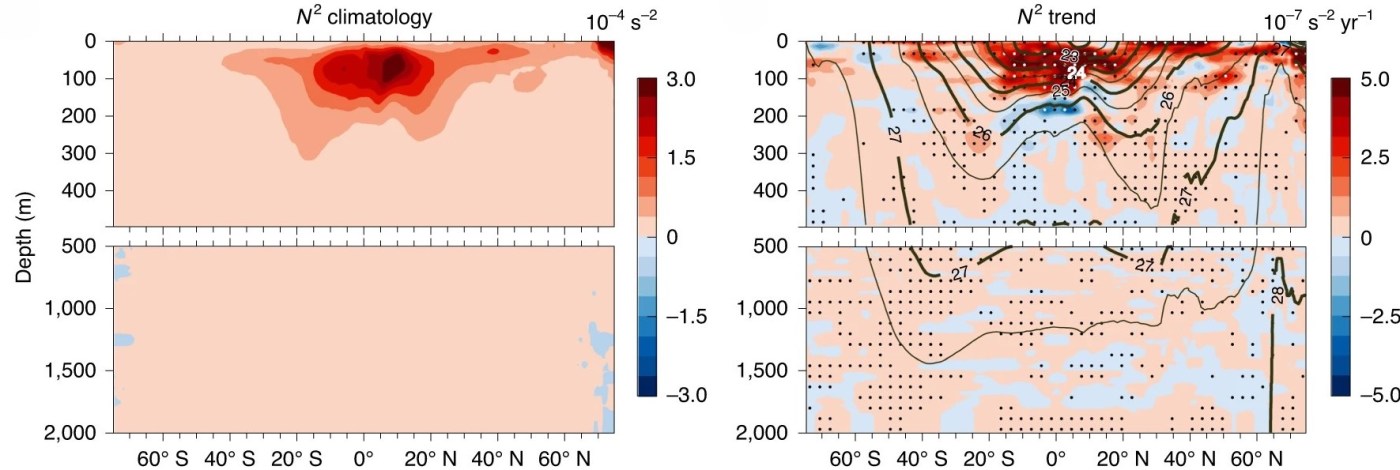

Figure 1c & d from Li et al. (2020). Zonal mean Brunt–Väisälä frequency N2, a measure of ocean stratification: (left) Climatology for 1981–2010, and (right) the long-term linear trends for 1960–2018. The stippled areas denote the signals significant at a 90% confidence level, accounting for the spatial sampling and instrumental uncertainty. Black contour lines show the climatology of potential density with 0.5 kg m–3 intervals.

Li, G., Cheng, L., Zhu, J. et al. Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 1116–1123 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00918-2

Jo, A. R., Lee, J.-Y., Timmermann, A., Jin, F.-F., Yamaguchi, R., & Gallego, A. (2022). Future amplification of sea surface temperature seasonality due to enhanced ocean stratification. Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL098607. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL098607

Liu, F., Song, F. & Luo, Y. Human-induced intensified seasonal cycle of sea surface temperature. Nat Commun 15, 3948 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48381-3

A related paper “Weakening of subsurface ocean temperature seasonality over the past four decades”: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-024-01986-4

It is possible that the extreme warming of North Atlantic in 2023 is linked to increasing stratification and shallower mixed layer depth according to the following studies:

England, M.H., Li, Z., Huguenin, M.F. et al. Drivers of the extreme North Atlantic marine heatwave during 2023. Nature 642, 636–643 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08903-5

Tianyun Dong et al. Record-breaking 2023 marine heatwaves. Science, 389, 369-374 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adr0910