This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Rainfall sustains multiyear La Niña” by Tian et al. (2026).

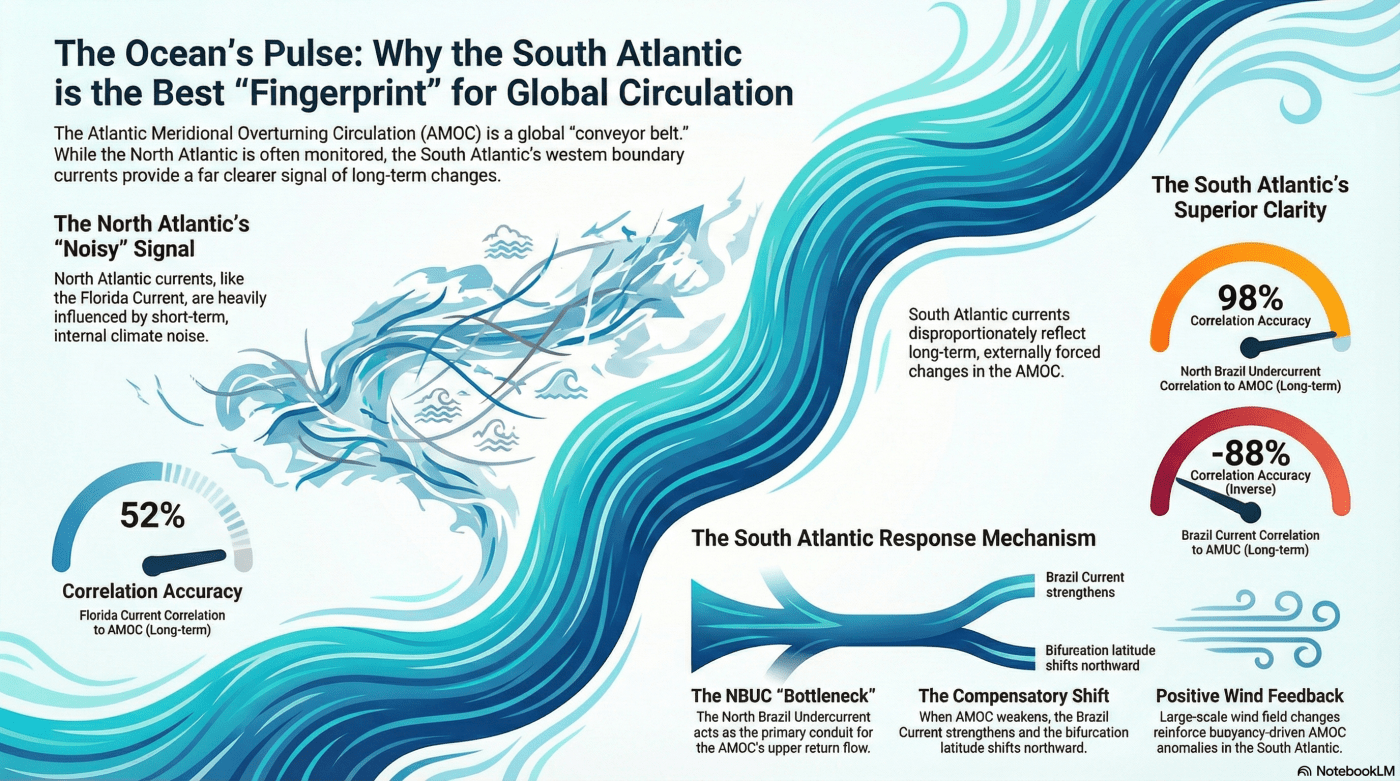

This research investigates how the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) imprints its signal on regional ocean currents, specifically comparing the North and South Atlantic. By analyzing 22,000 years of climate simulations, the authors demonstrate that long-term, externally forced changes in the AMOC are most clearly reflected in the South Atlantic western boundary current system. While North Atlantic currents like the Florida Current are heavily influenced by short-term internal variability and local winds, South Atlantic transports—such as the North Brazil Undercurrent and the Brazil Current—act as highly sensitive fingerprints of the overall overturning strength. The study concludes that these southern currents are superior indicators for monitoring the predicted weakening of the AMOC under modern anthropogenic forcing. Through mass conservation and planetary wave adjustments, the South Atlantic emerges as a critical region for understanding both past and future shifts in global ocean circulation.

The Ocean’s Hidden Pulse: Why the South Atlantic Is the Key to Tracking Climate Change

A 22,000-Year Mystery in the Deep

Imagine the Earth has a circulatory system—a vast, underwater “global conveyor belt” known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This system is responsible for moving heat, salt, and nutrients around the planet, regulating our climate and sustaining marine life. For decades, the scientific community has looked to the North Atlantic to monitor the health of this conveyor belt, watching the Gulf Stream for signs of trouble.

However, a new analysis of 22,000 years of ocean history suggests we have been operating under a geographical bias that has masked a planetary-scale signal. While the North Atlantic is where the “pulse” is traditionally measured, a study of the transition from the last Ice Age to the present reveals that the most reliable signals of the ocean’s long-term health are actually hidden in the Southern Hemisphere. Have we been eavesdropping on the wrong side of the Equator?

The South Atlantic: A High-Fidelity Climate Fingerprint

The research identifies the South Atlantic western boundary (SA-WB) transports as superior “fingerprints” for tracking long-term AMOC changes. While data from the North Atlantic is frequently obscured by internal stochastic noise, the South Atlantic provides a remarkably clear signal of how the entire system responds to external pressures like greenhouse gases or melting ice.

In oceanography, a “fingerprint” is a vital diagnostic tool. As defined in the study:

“Fingerprints of AMOC variability are defined as metrics that well represent an aspect of the AMOC… and are able to detect AMOC anomalies or changes in a given scenario.”

By analyzing 22,000 years of data, scientists found that the South Atlantic currents are significantly more attuned to the AMOC’s long-term health than the famous currents of the North. Using 10-decade low-pass filtered data, the correlation strengths reveal a stark contrast:

- North Brazil Undercurrent (NBUC) at 6°S: 97.89% correlation (A nearly perfect mirror of the AMOC).

- Brazil Current (BC) at 31°S: -87.79% correlation (A high-fidelity inverse relationship).

- Florida Current (FC) at 24°N: 52.04% correlation (A much weaker, noisier signal).

The North Atlantic’s “Noise” Problem

Why has the North Atlantic been so difficult to read? The issue lies in “unforced” or “internal” variability—short-term fluctuations caused by local processes, such as wind forcing, that obscure the long-term buoyancy signal.

The Florida Current (FC) and the Gulf Stream are heavily influenced by these internal climate system processes. While the Florida Current does respond to the underlying changes in ocean buoyancy that drive the AMOC, it does so primarily on shorter, less coherent timescales. This is proven by the fact that when the data is detrended to remove long-term signals, the Florida Current’s correlation with the AMOC jumps to 86.33%. This confirms that while the North Atlantic is sensitive to short-term “wobbles,” it is a poor sensor for the long-term, externally forced changes that characterize major climate transitions.

The NBUC: A High-Fidelity Gateway Between Hemispheres

One specific current stands out as a high-fidelity sensor for the entire planet: the North Brazil Undercurrent (NBUC). The NBUC acts as the ocean’s most reliable “bottleneck” for the upper limb of the AMOC.

This reliability stems from a unique “mutual exclusivity” in the tropical South Atlantic. The AMOC’s upper limb—the warm return flow destined for the North Atlantic—flows almost exclusively through the NBUC. Conversely, the NBUC carries almost exclusively the water required to compensate for the export of North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW). Because the NBUC acts as this singular gateway, its transport fluctuations serve as a high-fidelity mirror of the AMOC’s overall strength.

The Brazil Current: The Great Compensator

To maintain the ocean’s mass balance, the South Atlantic operates through a counter-intuitive inverse relationship. The NBUC and the Brazil Current (BC) are both fed by the same source: the southern South Equatorial Current (sSEC). This creates a “mass-balance” dynamic: if the AMOC strengthens and the NBUC requires more water, the BC must receive less.

Crucially, the “fingerprint” is not found in the total northward flow (the BeC-sSEC system), which remains relatively stable. The true climate signal only emerges once you account for the balance between these currents.

| AMOC State | NBUC Transport | BC Transport | Bifurcation (SBL) Shift |

| Strengthening | Increases | Decreases | Southward |

| Weakening | Decreases | Increases | Northward |

How Long-Term Trends Reorganize the Entire Ocean

A critical finding of the 22,000-year simulation is that long-term climate changes—forced by greenhouse gases or massive meltwater events—are not just larger versions of short-term internal variations. They actually “reorganize” the horizontal circulation of the Atlantic.

Short-term variations (the “noise”) remain largely concentrated in the North Atlantic. However, long-term forced changes “imprint” themselves across the entire meridional extent of the South Atlantic. As the climate shifts over millennia, the very pathways the water takes are altered, leaving a permanent mark on the currents of the Southern Hemisphere that the North Atlantic simply cannot match for clarity.

The Wind’s Positive Feedback Loop

In most of the ocean, wind acts as a disruptor. But in the South Atlantic, the physics of the “Sverdrup balance” work to reinforce the climate signal. The study found that wind stress curl actually supports the buoyancy signal rather than obscuring it.

When the AMOC is strong, it induces a wind field that reinforces equatorward transport. Conversely, during a weakening phase (such as the Younger Dryas), the wind stress curl spins up the core of the South Atlantic Subtropical Gyre (SASG). This “spin-up” reinforces the southward-flowing Brazil Current, which in turn balances the weakened AMOC. In essence, the wind and the water in the South Atlantic are “singing from the same songbook,” creating a positive feedback loop that makes the Southern signal remarkably robust.

Conclusion: Listening to the South

While the 22,000-year history used orbitally-driven changes as a laboratory, the underlying physics apply directly to our current era of rapid anthropogenic warming. This “past as prologue” is vital: the study notes that modern CO2 rise and ice loss are occurring at rates that exceed those of past natural interglacial conditions by orders of magnitude.

As the AMOC is predicted to weaken due to human activity, the most critical warnings will not come from the North Atlantic’s famous currents. Instead, the “vital signs” of our planet will be found in the subtle, high-fidelity shifts of the currents bordering Brazil and South Africa. In our race to monitor the planet’s vital signs, are we finally ready to listen to what the South Atlantic is trying to tell us?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Marcello, F., Wainer, I., de Mahiques, M.M. et al. Forced changes in Atlantic overturning are distinctly fingerprinted by South Atlantic western boundary transports. Commun Earth Environ 7, 184 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-026-03282-9

Leave a comment