This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Atlantification drives recent strengthening of the Arctic overturning circulation” by Årthun et al. (2026).

A recent study examines how Atlantification, the northward expansion of warm Atlantic waters, is altering the Arctic overturning circulation. While traditional source regions for dense water in the Nordic Seas have seen a decline in activity, this loss is being offset by increased water mass transformation further north due to receding sea ice. Researchers used high-resolution ocean reanalysis and observational data to confirm that this poleward shift has kept the supply of dense overflow waters to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) stable. These findings suggest that the Arctic environment exhibits a surprising level of resiliency despite rapid climate change. Ultimately, the research highlights that a stronger Arctic overturning is an ongoing reality that helps sustain global ocean currents.

The Hook: A Climate Paradox

For decades, physical oceanographers have monitored the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) with growing trepidation. The prevailing narrative is one of fragility: as the planet warms and Arctic ice melts, the influx of freshwater and rising temperatures should theoretically stifle the “engine” of the global ocean, leading to a catastrophic slowdown of the currents that regulate our climate.

However, a landmark study by Årthun et al. (2025) reveals a fascinating paradox. While the traditional cooling centers in the Nordic Seas are indeed showing signs of buoyancy flux reduction, the northernmost terminus of this system—the Arctic Ocean itself—is actually revving up. Between 1993 and 2020, the Arctic’s internal overturning circulation has strengthened. Far from being a passive victim of climate change, the Arctic is currently acting as a stabilizing force, “picking up the slack” for its southern neighbors and maintaining the steady flow of dense water into the deep global ocean.

Here are the five most impactful takeaways from this research into the ocean’s shifting machinery.

The Arctic’s New Engine: How “Atlantification” Boosts Circulation

We typically associate sea-ice loss with climate failure, but in the specific context of oceanography, it is driving a process called “Atlantification.” This is the poleward expansion of warm Atlantic Water (AW) and the retreat of sea ice, which fundamentally changes the ocean’s interaction with the atmosphere.

As a Physical Oceanographer, I look at the “isopycnal outcropping area”—the region where specific density surfaces meet the ocean’s surface. In the Nordic Seas, the outcropping area of the 27.8 kg m⁻³ density surface is shrinking. However, as sea ice retreats further north, it exposes the warm Atlantic Water boundary currents to the freezing winter atmosphere. This allows for “enhanced surface water mass transformation” via intense surface buoyancy fluxes (heat loss). Effectively, the water loses its buoyancy and densifies more efficiently in these newly exposed Arctic regions.

“In contrast, an encroaching ‘Atlantification’ from the expansion of Atlantic waters into the Arctic Ocean has been accompanied by a recent sea-ice retreat that has partially uncovered the boundary current, leaving it exposed to the atmosphere in winter, which allows for further modification of the AW during transit.” (Introduction, Årthun et al., 2025)

The Great Poleward Shift: Moving the Source of Dense Water

The “heart” of the ocean’s sinking mechanism is migrating. The data shows that dense water formation is decreasing in the Nordic Seas, but this is being compensated for by a geographic shift into the Arctic Ocean—specifically the northern Barents Sea and the Nansen Basin (north of Svalbard).

This “geographic compensation” is remarkably precise. The researchers found that the increase in water mass transformation in the Barents Sea (0.2 sverdrup) and north of Svalbard (0.4 sverdrup) accounts perfectly for the 0.6 sverdrup total increase in Arctic overturning observed during the study period. For context, 1 sverdrup (Sv) represents a flow of one million cubic meters of water per second. To visualize the scale:

- The Greenland-Scotland Ridge (GSR): The primary exit for deep water into the Atlantic, with a maximum overturning of 5.2 sverdrup.

- The Arctic Gateways: Combined flow across the Fram Strait and Barents Sea Opening, totaling 2.1 sverdrup.

A Resilient “Safety Valve” for the Global Ocean

The most significant discovery for global climate stability is the sheer resilience of the system. Between 1993 and 2020—a period of unprecedented Arctic warming—the volume of dense “overflow” water moving across the Greenland-Scotland Ridge (GSR) into the North Atlantic remained remarkably stable.

The Arctic Ocean is essentially acting as a “safety valve.” By increasing its own internal overturning through enhanced transformation and diapycnal mixing (the mixing of water across different density layers), it ensures the lower limb of the AMOC remains supplied even as southern formation zones falter.

“Our results thus provide evidence for a resilient northern overturning circulation in a warming climate.” (Results/Discussion, Årthun et al., 2025)

The Changing “Flavor” of Deep Water: Warming the Abyss

While the volume of the conveyor belt is steady, its physical properties—or what we call its “flavor”—are changing. The study indicates that while the “engine” is still running at the same speed, it is pumping more heat into the deep ocean.

The data reveals a nuance in how this warming is distributed:

- Faroe-Shetland Channel: This major overflow branch is warming significantly, at a rate of 0.08°C to 0.10°C per decade.

- Denmark Strait: Interestingly, the other major overflow branch shows no significant warming trend, though it exhibits high year-to-year variability.

This means that the conveyor belt is maintaining its speed, but it is now transporting an increasing amount of heat into the deep ocean, which has long-term implications for the global heat budget and sea-level rise.

Why Our Current Models Might Be Wrong: The Resolution Gap

One of the most sobering takeaways concerns our ability to predict the future. The authors highlight a critical failure in current climate modeling: resolution. Most standard climate models use a “coarse” 1-degree resolution.

At that scale, models are essentially blind to the narrow boundary currents—like the West Spitsbergen Current—where this vital water transformation actually occurs. Because these models cannot “see” the detailed interactions between the atmosphere and these narrow ribbons of water, they likely underestimate the Arctic’s ability to stabilize the AMOC. If our models can’t resolve these boundary processes, they may be projecting a collapse that the Arctic is currently working hard to prevent.

Conclusion: A Ponderable Future

The research by Årthun et al. (2025) suggests that the northern limb of the global ocean circulation is far more robust than we feared. We are seeing a system in transition, shifting its operations poleward to maintain its vital function.

However, we must ask: how long can this “buffer” last? The future of this resilience depends on the tug-of-war between internal climate variability (natural cycles) and the relentless march of long-term warming. Will there come a point where the Arctic atmosphere is too warm to allow Atlantic water to cool down even when the ice is gone? Or will “Atlantification” continue to provide the open-water runway the ocean needs to keep its great conveyor belt moving?

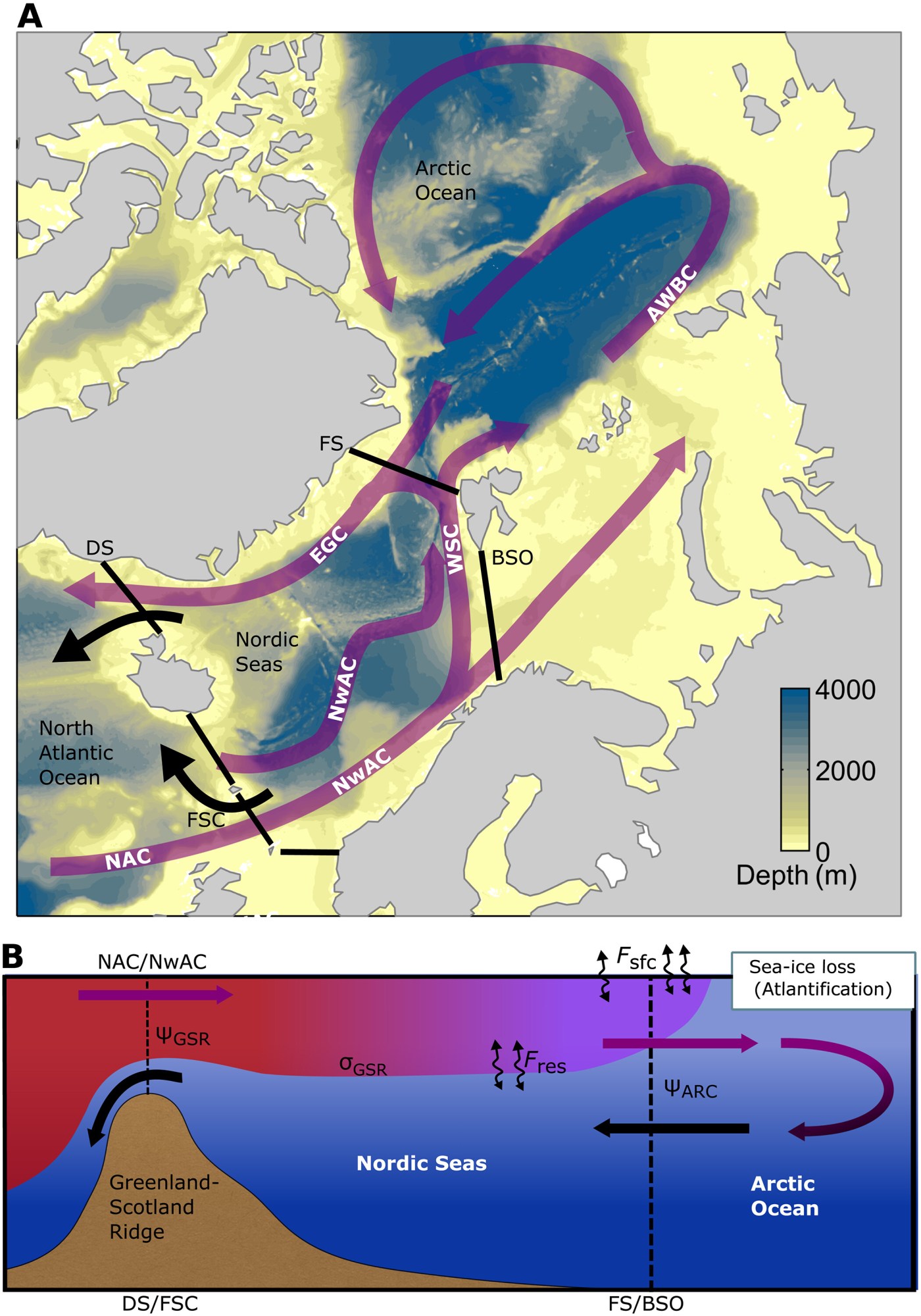

Figure 1 from Årthun et al. (2025): The overturning circulation in the Nordic Seas and Arctic Ocean. (A) Horizontal view of the ocean circulation in the Nordic Seas and Arctic Ocean. Warm Atlantic Water (AW) is transported northward by the North Atlantic Current (NAC), Norwegian Atlantic Current (NwAC), and West Spitsbergen Current (WSC). The AW enters the Arctic Ocean through the Barents Sea Opening (BSO) and Fram Strait (FS) and flows along the Atlantic Water Boundary Current (AWBC), before returning southward in the East Greenland Current (EGC). Cold, dense overflows (black arrows) exit the Nordic Seas through Denmark Strait (DS) and Faroe-Shetland Channel (FSC). The background color shows bottom depth in GLORYS12. (B) Vertical view of the overturning circulation in the Nordic Seas and Arctic Ocean. The terms used in the isopycnal volume budget used to quantify overturning changes are included.

Årthun, M., A. Brakstad, J. Dörr, H. L. Johnson, C. Mans, S., Semper, & K. Våge, (2025). Atlantification drives recent strengthening of the Arctic overturning circulation. Sci. Adv. 11, eadu1794(2025). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adu1794

Leave a comment