This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “The Arctic overturning circulation: transformations, pathways and timescales” by Dörr et al. (2026).

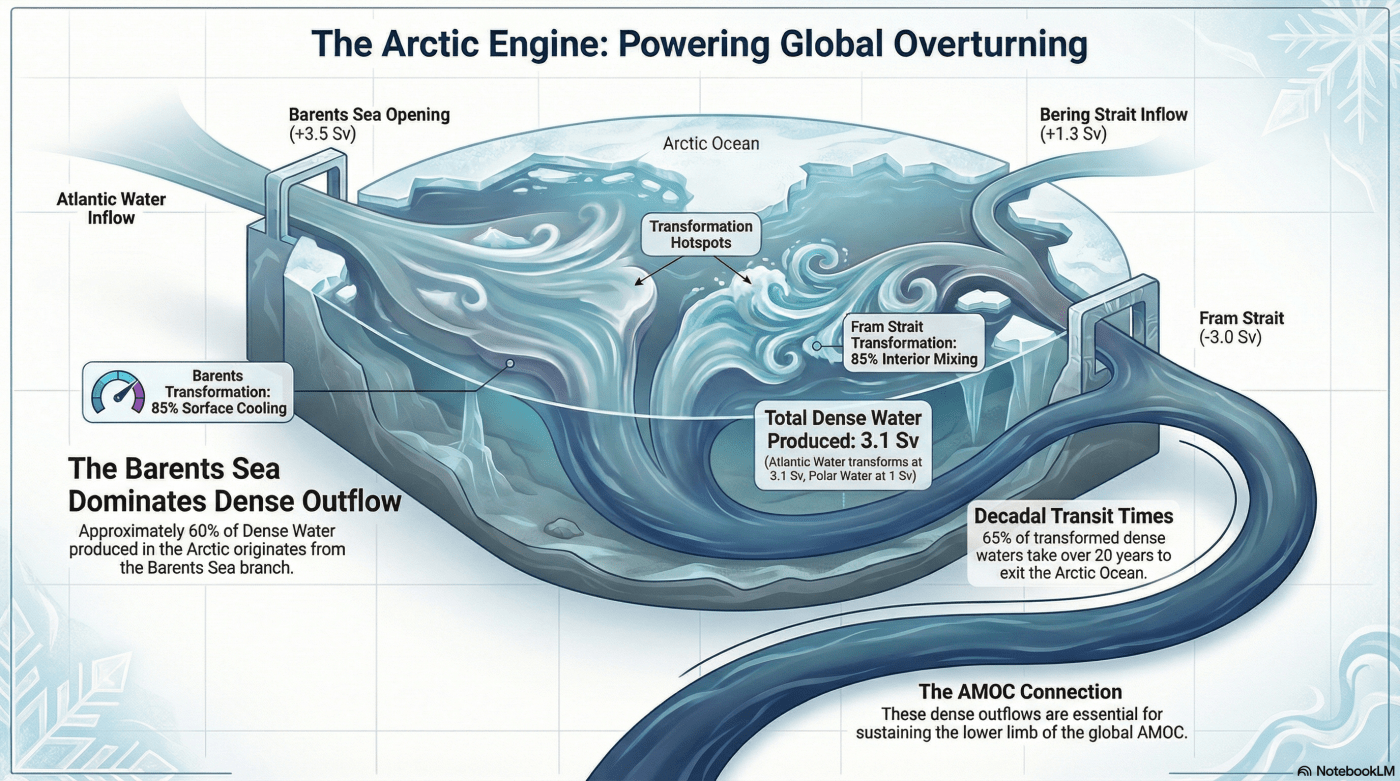

Dörr et al. (2026) investigates the Arctic overturning circulation by analyzing how warm Atlantic Water is converted into Dense and Polar Waters. Utilizing a high-resolution ocean model and Lagrangian tracking, the authors reveal that the Barents Sea branch is the primary driver of dense water formation, largely due to surface heat loss. While atmosphere-driven cooling dominates this densification, interior mixing remains a critical factor for the Fram Strait branch and the production of buoyant Polar Waters. The study establishes that most transformed waters require several decades to exit the Arctic and rejoin the global circulation. These findings provide a vital baseline for predicting how future sea-ice loss and warming will impact the stability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation.

The 20-Year Commute: Why the Arctic is the Slow-Burning Engine Room of Global Climate

1. Introduction: The Mystery at the North Pole

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is the planet’s most famous thermostat. We often visualize this “global conveyor belt” as a streamlined loop of warm surface currents and cold deep-water returns. Yet, for decades, the northernmost terminus of this system—the Arctic Ocean—has remained something of a “black box” in climate models. We knew the conveyor belt reached the high north, but the precise mechanics of how the Arctic transforms warm Atlantic inflows into the frigid, heavy waters that power the global deep-sea return remained elusive.

New research from Dörr et al. (2026) has finally illuminated the internal “plumbing” of this engine room. By employing two distinct scientific lenses, researchers have quantified the Arctic’s contribution to global stability. They used an Eulerian framework—essentially watching the river from a bridge to measure transformations at a fixed grid—and paired it with Lagrangian trajectories, a method akin to following a leaf down a stream to map the specific journeys of individual water parcels. This dual approach reveals that the Arctic isn’t just a destination; it is an active refinery transforming 3.1 Sverdrups (Sv) of Atlantic Water into the densest components of the global ocean.

2. The Barents Sea is the Arctic’s True Heavyweight

Atlantic Water enters the Arctic through two primary gateways: the deep Fram Strait and the relatively shallow Barents Sea Opening. While the sheer depth of the Fram Strait might suggest it does the heavy lifting, the study identifies the Barents Sea as the Arctic’s true “Cooling Machine.”

The Barents Sea branch dominates dense water production, accounting for approximately 60% of the Arctic’s total dense overturning. The secret to its efficiency lies in its bathymetry. Because the sea is shallow, the atmosphere is able to “reach” and homogenize the entire water column, allowing for massive surface heat loss that preconditions the water before it sinks and moves into the deep basins. In contrast, the deeper Fram Strait branch contributes roughly 40%, primarily within a narrower, high-density range.

“We show that the Atlantic Water branch through the Barents Sea dominates dense Arctic overturning, and that a large portion of these transformed waters takes many decades to exit Fram Strait.”

3. The 20-Year Commute: Ocean Circulation Moves at a Snail’s Pace

While the surface “Transpolar Drift” can whisk ice across the Arctic in a few years, the deep-water overturning operates on a generational timeline. Using Lagrangian tracking, the researchers discovered that the Arctic possesses a remarkably “long memory,” with transformations taking place at a glacial pace.

- The 10-20 Year Cohort: Approximately 25% of the total overturning involves water that performs a “quick” loop, recirculating within the Eurasian Basin along the Gakkel and Lomonosov Ridges before exiting within two decades.

- The 20+ Year “Commute”: A staggering 65% of the total Arctic overturning is composed of water that takes longer than 20 years to exit. These parcels are often circumnavigating the Amerasian Basin, a slow-burning journey that delays the signal of surface changes.

This decades-long lag time means the deep basins act as a thermal shock absorber. The record-breaking sea-ice melt we observe today may not be fully reflected in the global AMOC strength until the mid-21st century.

4. Internal Mixing: The Invisible Architect of the Deep

While surface weather drives the Barents Sea, “internal mixing” is the silent architect shaping the water that enters through the Fram Strait. The study reveals that the transformation isn’t just about the atmosphere; it’s about how different ocean branches “talk” to each other in the dark.

Interior mixing accounts for 85% of the transformation within the Fram Strait branch. This process occurs at critical geographic crossroads where the different branches of Atlantic Water meet and collide:

- The St. Anna Trough: A vital junction where the cold, dense Barents branch sinks under and mixes with the warmer, saltier Fram branch, homogenizing their properties.

- The Nansen Basin: A region along the shelf break where inflowing waters interact with cold halocline and shelf waters, setting the final characteristics of the deep-sea return.

Across the entire Arctic, this invisible mixing contributes approximately 25% to the total dense overturning, proving that the “engine” is powered as much by internal turbulence as by surface cooling.

5. The “Double Estuary” and the Paradox of a Warming Arctic

The Arctic functions as a “double estuary,” refining Atlantic Water into two distinct exports: Dense Water (the thermal branch feeding the AMOC) and Polar Water (the estuarine branch of buoyant, fresh meltwater).

As the region continues to “Atlantify”—becoming warmer and saltier as Atlantic influences push further north—we face a counter-intuitive paradox. Conventional wisdom suggests that a warming Arctic would weaken ocean circulation. However, the loss of sea ice may actually stabilize the northern overturning in the short term. Without an ice lid, Atlantic Water is directly exposed to the cold polar atmosphere, which could paradoxically increase surface cooling and densification even as the planet warms.

In the Arctic Ocean, sea-ice loss might lead to a stronger surface exposure of Atlantic Water and hence increased dense water formation, potentially stabilizing the northern overturning circulation.

6. Conclusion: A Baseline for a Changing World

The Dörr et al. (2026) study provides a definitive baseline for the Arctic’s role as the producer of the world’s “densest waters.” The identified 3.1 Sv rate of dense water formation is more than just a data point; it is the “fuel” for the global conveyor belt, representing a significant portion of the total AMOC strength.

However, the “long memory” of these pathways remains the great climate wildcard. If 65% of the Arctic’s dense output takes over twenty years to reach the global stage, we are currently living with an ocean circulation shaped by the Arctic of the early 2000s. As we reshape the “engine room” through rapid sea-ice loss, we must ask: what kind of global conveyor belt are we preconditioning for the decades to come?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Dörr, J., Mans, C., Årthun, M., Döös, K., Evans, D. G., and He, Y.: The Arctic overturning circulation: transformations, pathways and timescales, Ocean Sci., 22, 565–585, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-22-565-2026, 2026.

Leave a comment