This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on a preprint article “Relatively warm deep-water formation persisted in the Last Glacial Maximum” by Wharton et al. (2026).

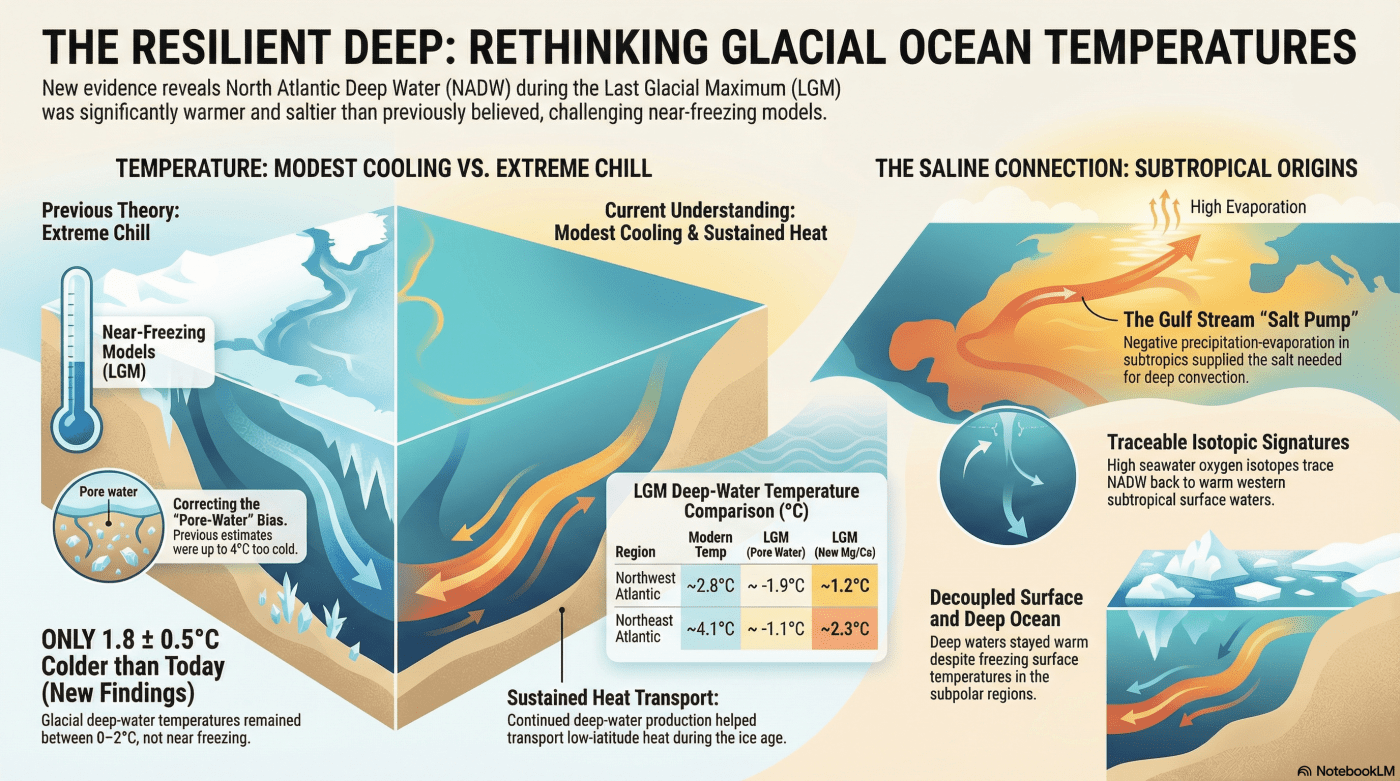

This research investigates the state of the deep North Atlantic Ocean during the Last Glacial Maximum, challenging previous theories that the deep sea was near freezing. By analyzing geochemical tracers in marine sediment cores, scientists discovered that deep-water temperatures were only about 1.8°C colder than modern levels. The findings suggest that North Atlantic Deep Water production was sustained by relatively warm, salty surface currents originating from the subtropics. This persistent circulation was likely driven by atmospheric changes and increased evaporation, which maintained the density necessary for deep-water formation despite a colder climate. These new temperature and salinity constraints offer a vital benchmark for improving Earth system models used to forecast future climate scenarios. Overall, the study highlights a significant decoupling between freezing surface conditions and the resilient warmth of the deep glacial ocean.

The Ice Age’s Secret Heater: Why the Deep Atlantic Refused to Freeze

Twenty thousand years ago, during the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), the northern hemisphere was a landscape of stark, crushing extremes. Massive ice sheets, kilometers thick, smothered North America and Northern Europe. The world was at least 6°C colder on average, and the North Atlantic surface was a treacherous expanse of ice and sub-freezing slush. For decades, the scientific consensus regarding the deep ocean—the vast world below 1.5 kilometers—was equally grim: researchers envisioned a stagnant, near-freezing pool of brine, effectively a “cold case” where the circulation had slowed to a glacial crawl.

However, a new investigation into the chemistry of the deep is turning this narrative of a frozen abyss on its head. Using sophisticated geochemical “clocks” and “thermometers” locked within microscopic fossils, scientists have discovered that the deep Northwest Atlantic was not the icy graveyard we once imagined. Instead, it was a surprisingly warm, salty refuge that remained resilient even as the surface world froze over.

The Thermal Resilience of a Frozen World

The quest to reconstruct the LGM (which peaked between 19,000 and 23,000 years ago) relies on tiny, calcified time capsules: benthic foraminifera. These single-celled organisms, such as the aragonitic Hoeglundina elegans or the deep-dwelling Globobulimina affinis, build their shells using the chemical signatures of the surrounding seawater. By measuring magnesium-to-calcium (Mg/Ca) ratios and “clumped isotopes” (Δ47) within these shells, paleoceanographers can reconstruct temperatures from tens of thousands of years ago with startling precision.

The results are provocative. While previous estimates derived from sedimentary “pore-water” suggested the deep Atlantic hovered near the freezing point—between -1.1°C and -1.9°C—this new data reveals a much milder reality. The deep Northwest Atlantic (>1.5 km) actually maintained temperatures between 0°C and 2°C.

“Here we show that the temperature of the glacial deep (>1.5 km) Northwest Atlantic was approximately 0–2 °C (only 1.8 ± 0.5 °C (2 s.e.) colder than today).”

This means the deep ocean was only about 1.8°C cooler than modern temperatures at the same depths. The earlier pore-water data was likely skewed by a flawed assumption: that regional salinity changes always scaled perfectly with global ice volume. By using independent proxies like clumped isotopes and trace metals, researchers have proven that the deep ocean possessed a thermal resilience that defies the “frozen abyss” model.

The Subtropical Engine: Salinity as a Lifeline

How did the deep ocean stay so warm when the world above was an ice box? The answer lies in a persistent “salt pump” fueled by the subtropics. To solve this mystery, scientists traced the isotopic signature of seawater—specifically δ18O—which acts as a proxy for salinity.

Even at the height of the Ice Age, the great arteries of the ocean—the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Current (NAC)—never stopped pumping. In fact, the glacial climate may have supercharged this process. Stronger, colder, and drier westerlies whipped across the subtropical Atlantic, driving intense evaporation. This created a “negative P−E” (precipitation minus evaporation) regime, effectively “pre-salting” the surface waters.

As this dense, salty water moved toward the subpolar regions, it carried a significant amount of subtropical heat with it. This “pre-salted” water was so dense that it could sink and form North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) before it ever reached the freezing point. This persistent salt pump ensured that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)—the global conveyor belt of heat—continued to function, albeit in a modified form.

The Latitudinal Shift: A Survival Mechanism in the Deep

Perhaps the most fascinating revelation is the “surface–deep-ocean decoupling” that occurred as the planet cooled. While subpolar surface waters were locked in ice, the deep water stayed relatively warm because the site of deep-water formation shifted south.

This was a matter of physical necessity. At extremely low temperatures, the “buoyancy flux”—the change in density caused by cooling—is significantly reduced. Furthermore, the water column becomes more “haline stratified,” a state where salinity differences create a lid that inhibits deep mixing. To keep the conveyor belt moving, the ocean pivoted. Convection centers migrated to warmer, more southerly latitudes where surface cooling could still effectively trigger the sinking of salty water.

Evidence for this shift is found at site ODP-172-1055 on the Blake Outer Ridge. While much of the deep Atlantic was 0–2°C, this site remained substantially warmer, at approximately 5°C, reflecting the direct influence of a deeper and more vigorous subtropical gyre. This geographic flexibility acted as a survival mechanism, allowing the AMOC to adapt its origin points to maintain circulation.

A Calibration for the Anthropocene

These findings do more than rewrite natural history; they provide a critical benchmark for the future. We know from global data that the Mean Ocean Temperature (MOT) during the LGM was roughly 2.3°C colder than today. If the North Atlantic only cooled by 1.8°C, it implies that other water masses, such as Pacific Deep Water or Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), must have cooled far more dramatically to balance the global average.

This highlights the Atlantic’s unique role as a thermal powerhouse. However, it also exposes a gap in our current Earth system models. Many of the simulations used to project 21st-century climate change struggle to replicate how the North Atlantic stayed so warm during the LGM. If our models cannot accurately simulate the “flexible” ocean of the past—where deep-water formation sites shifted and stayed salty—we may be underestimating how the ocean will react to modern warming.

The deep Atlantic was never a passive, frozen void; it was a dynamic, salt-driven engine that resisted the glacial chill. Today, as we watch deep-water formation sites in the North Atlantic shift once again due to melting ice and changing winds, we are reminded of the ocean’s historic capacity for change. The question is no longer whether the ocean’s conveyor belt is flexible, but rather: as the “flexible” ocean of the past meets the rapid warming of the future, are we prepared for the new circulation patterns it might choose next?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Wharton, J.H., Kozikowska, E., Keigwin, L.D. et al. Relatively warm deep-water formation persisted in the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature 650, 116–122 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-10012-2

Leave a comment