This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Impacts of eastern Arctic Eurasian Basin water mass properties on the AMOC and Beaufort Sea Atlantic water layer.” by Wei and Zhang (2026).

Wei and Zhang (2026) investigates how water mass properties in the eastern Eurasian Basin influence global ocean patterns and regional Arctic structures. By utilizing a coupled climate model constrained by observed data, the authors demonstrate that colder, saltier conditions in the eastern Arctic increase the density of the Arctic outflow, which strengthens the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) at deeper levels. These findings confirm the Arctic’s role as the northern terminus of the AMOC, providing the essential dense water that drives this global circulation. Additionally, the study reveals that biases in modeled Atlantic Water layers in the Beaufort Sea are often caused by inaccuracies in the upstream Eurasian Basin. Ultimately, the paper highlights the Eurasian Basin as a critical region for improving the accuracy of climate simulations regarding both the North Atlantic and the broader Arctic environment.

The Arctic’s Secret Switch: How a Remote Basin Steers a Global Ocean Current

Introduction: The Planet’s Beating Heart

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is one of the planet’s most powerful climate engines. Often called a “global ocean conveyor belt,” it transports immense quantities of heat from the tropics northward, governing weather from the Sahara to Scandinavia and ensuring planetary climate stability. To understand this colossal system, scientists rely on sophisticated models, but these simulations often struggle to capture the complex, rapidly changing dynamics of the Arctic Ocean.

The engine of this deep circulation is driven by a simple principle: density. In the ocean, cold, salty water is denser than warm, fresher water, causing it to sink and drive deep currents. A recent study has uncovered surprising new insights by focusing on one key region of the Arctic, revealing its outsized influence on this entire global system and reshaping our understanding of climate modeling.

1. The Deep Atlantic Conveyor Belt Actually Starts in the Arctic

While we often picture warm tropical waters driving the ocean’s surface currents, this new research reinforces a crucial truth: the deep, cold return-flow of the AMOC is critically dependent on what happens at the top of the world. The study confirms the view of the Arctic as the “northern terminus” of this massive system—the place where the densest waters that feed the entire deep ocean conveyor are born. This finding transforms our view of the Arctic from a remote, frozen sea to the very heart of the Atlantic’s deep-water engine.

The study’s authors state this finding unequivocally:

“The results support that the Arctic is the northern terminus of the AMOC and the Arctic outflow provides the densest water to the AMOC”

This establishes the Arctic as the system’s starting point, but the next critical insight from this study is how exquisitely sensitive the entire AMOC is to the precise character of the water born there.

2. A Colder, Saltier Arctic Outflow Makes the Global Conveyor Belt Denser

At the core of the study was an elegant experiment. Using a well-established computational technique, scientists constrained their model with real-world observational data from the eastern Arctic Eurasian Basin, adjusting the model’s water properties to reflect the colder and saltier conditions observed in reality. They then watched to see what effect this single, targeted change would have on the rest of the global system.

The primary result was striking. This more realistic, and therefore denser, water flowing out of the Arctic (the “Arctic outflow”) didn’t just strengthen the AMOC; it fundamentally changed its character. The circulation shifted to operate at deeper, denser, and more realistic levels, better matching real-world observations. The key effect wasn’t about raw power, but about precision and depth.

A denser Arctic outflow leads to denser Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) across Arctic‐ Atlantic gateway sections and the eastern subpolar North Atlantic

This finding demonstrates just how sensitive the massive AMOC system is to the specific density of the water feeding it from one remote corner of the Arctic Ocean.

3. Getting One Obscure Arctic Basin Right Fixes Problems Thousands of Kilometers Away

For years, climate models have been plagued by a persistent mystery: they frequently simulate an “unrealistically warm and thick” layer of Atlantic Water in the Canadian Basin and the Beaufort Sea. It’s a problem scientists believe is linked to how models simulate the formation of dense water on the shallow Arctic shelves.

This study made a remarkable discovery that helps solve this puzzle. When the scientists corrected the water properties in the upstream eastern Eurasian Basin, the model automatically fixed the long-standing bias in the downstream Beaufort Sea, producing a more realistic, colder, and thinner Atlantic Water layer. This “ripple effect” perfectly illustrates the profound interconnectedness of the Arctic Ocean. A modeling error in one obscure basin can create what appear to be unrelated problems thousands of kilometers away.

The eastern Eurasian Basin is a key region causing modeled Atlantic Water layer thermal biases in the downstream Canadian Basin/Beaufort Sea

This breakthrough is crucial for improving the accuracy of future climate models. By pinpointing the source of a chronic bias, scientists can now build far more reliable simulations of our planet’s climate system.

Conclusion: What the Arctic Tells the World

This research delivers a powerful message. It confirms the Arctic’s foundational role in driving the global ocean conveyor belt, reveals the circulation’s acute sensitivity to the density of Arctic water, and uncovers a hidden connection between ocean basins that can solve long-standing problems in climate science.

The study shows that the stability of our planet’s climate is intricately tied to the physical state of a remote sea at the top of the world. As the Arctic continues to warm and change at an alarming rate, this research sharpens the most urgent question of all: as the system’s source water is irrevocably altered, how will the reverberations be felt across the entire globe?

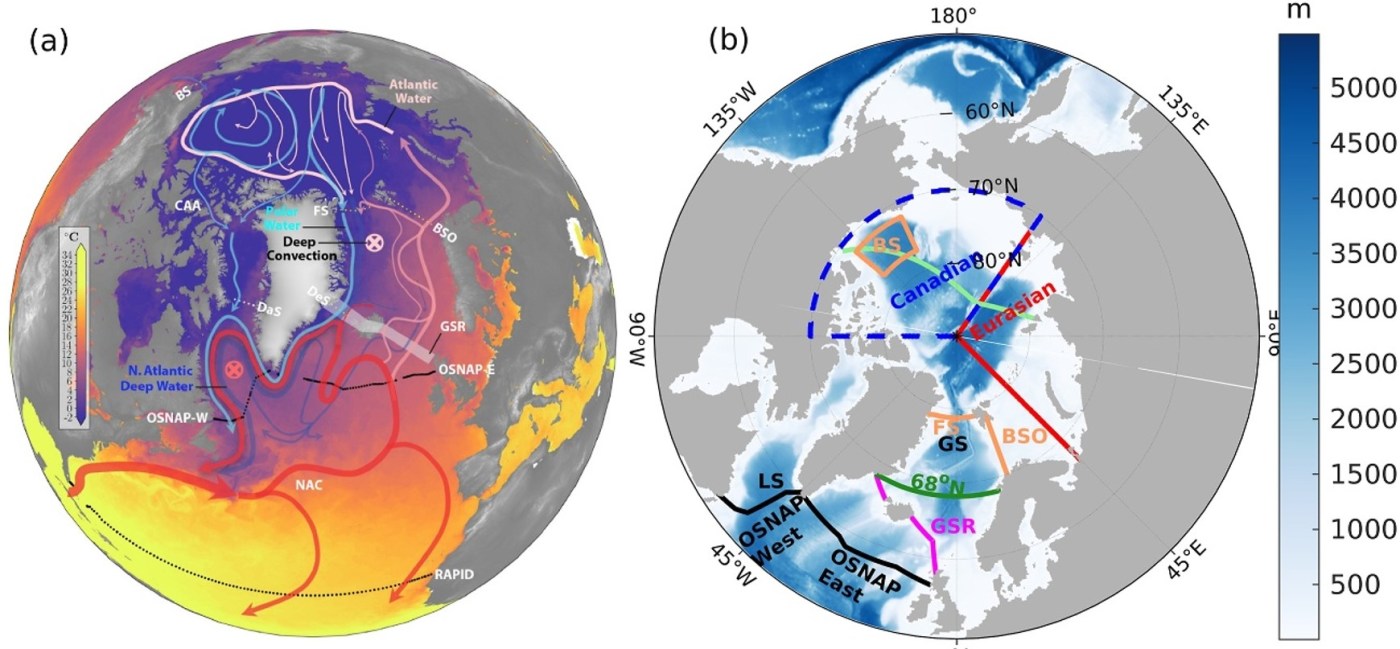

Figure 1 from Wei and Zhang (2026): (a) Schematic ocean circulation overlapped with observed sea surface temperature. BS: Bering Strait. CAA: Canadian Arctic Archipelago. FS: Fram Strait. BSO: Barents Sea Opening. DaS: Davis Strait. DeS: Denmark Strait. GSR: Greenland‐Scotland Ridge. NAC: North Atlantic Current. OSNAP‐W/OSNAP‐E: Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP) West/East subsection. RAPID: section for the Rapid Climate Change program. (b) Bathymetry over the Arctic/subpolar North Atlantic. Red lines: eastern Arctic where RDC is applied (north of 66°N, 45°E-145°E). Dashed blue lines: area covering Canadian Basin. Orange/green/magenta/back lines: four sections across FS/BSO, 68°N in the Nordic Sea, GSR, and OSNAP West/East subsection. LS: Labrador Sea. GS: Greenland Sea. BS: Beaufort Sea (orange box).

Wei, X., & Zhang, R. (2026). Impacts of eastern Arctic Eurasian Basin water mass properties on the AMOC and Beaufort Sea Atlantic water layer. Geophysical Research Letters, 53, e2025GL119128. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL119128

Leave a comment