This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Future Shoaling of the AMOC and Its Impact on Oceanic Heat Transport to the Subpolar North Atlantic” by Lee et al. (2026).

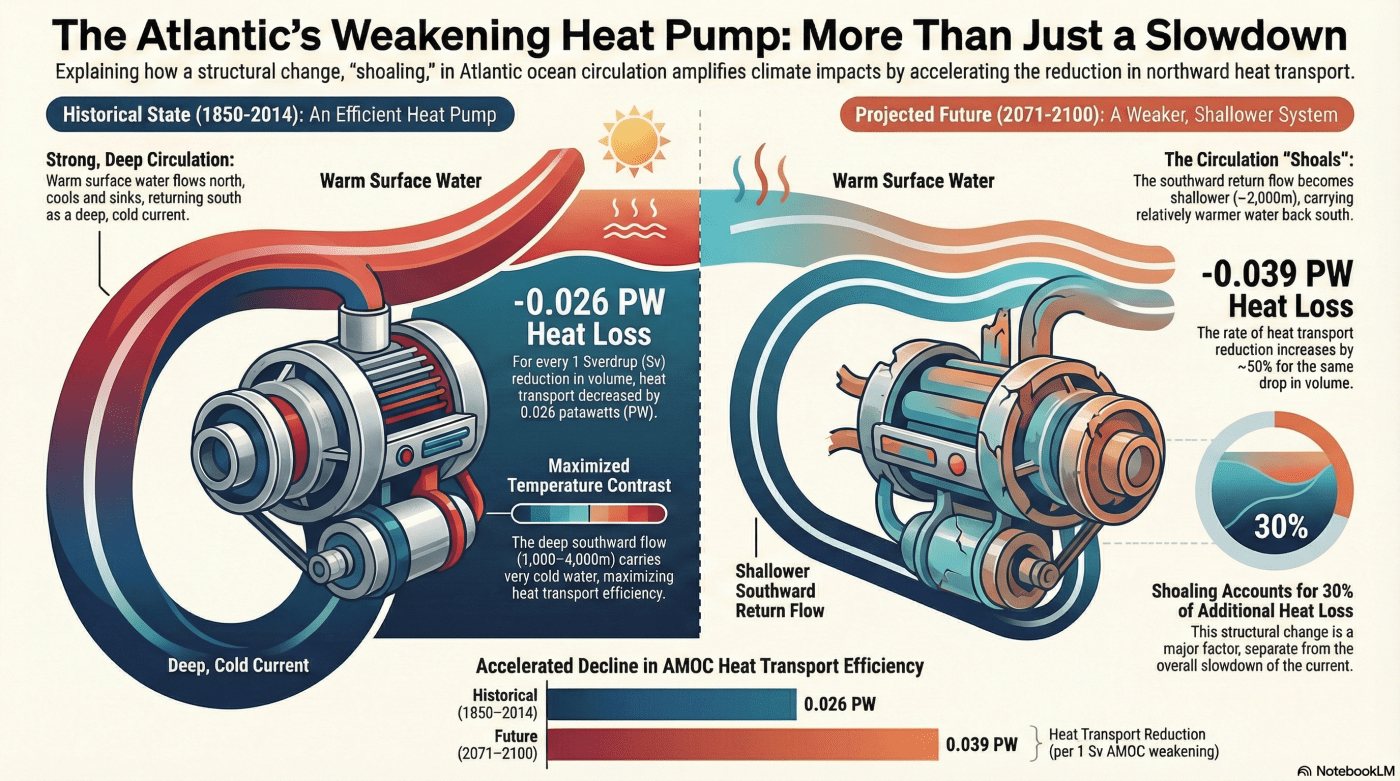

Research by Lee et al. (2026) investigates how greenhouse gas emissions will alter the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and its ability to move heat toward the subpolar North Atlantic. Using climate model simulations, the authors demonstrate that oceanic heat transport will decline more drastically than can be explained by a simple slowing of the current’s speed. This accelerated drop is caused by shoaling, a process where the southward-flowing lower limb of the conveyor belt becomes shallower and carries warmer water away from the poles. This structural shift reduces the temperature contrast between the ocean’s upper and lower layers, making the entire system less efficient at regulating climate. These findings suggest that the future reduction in heat delivery will be more severe than previously anticipated, contributing to the formation and strengthening of a “warming hole” in the North Atlantic.

Introduction: The Ocean’s Engine is Sputtering

Think of the Atlantic Ocean as having a massive engine—a great “ocean conveyor belt” that regulates our planet’s climate. Known scientifically as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), this system plays a vital role by transporting warm surface water from the tropics northward. As this water reaches the high-latitude North Atlantic, it cools, gets denser, and sinks into the deep ocean before returning south. This constant circulation is crucial for distributing heat and shaping global weather patterns.

For years, scientists have warned that this critical conveyor belt is weakening due to climate change. But new research reveals a more alarming problem. The AMOC isn’t just losing speed; it’s also becoming fundamentally less effective at its job of moving heat. This hidden inefficiency suggests the AMOC’s decline may not be a gentle, predictable slope, but an accelerating curve, with climate consequences that could arrive faster and with greater force than our previous models suggested.

1. It’s Not Just Slowing Down—It’s Becoming Less Efficient

According to new climate models, the projected drop in heat transported to the North Atlantic is much larger than what can be explained by the slowdown in the AMOC’s flow rate alone. The system isn’t just moving less water; it’s also getting worse at carrying heat with the water it does move.

This growing inefficiency can be quantified by looking at the relationship between the volume of water the AMOC moves (measured in Sverdrups, or Sv) and the amount of heat it transports (measured in petawatts, or PW).

- Historically (1850–2014): A reduction of 1 Sv in the AMOC’s flow corresponded to a 0.026 PW drop in heat transport.

- Future Projections (2071–2100): That same 1 Sv reduction is projected to cause a much larger 0.039 PW drop in heat transport.

This represents a nearly 50% increase in inefficiency—for every unit of water flow it loses, the AMOC will shed heat 50% faster in the future than it did in the past. This non-linear decline is deeply concerning. It suggests that as the AMOC continues to weaken, the climatic consequences will accelerate, leading to disruptions more severe than earlier linear models predicted.

2. The Surprising Culprit: A “Shoaling” Current

The key insight from the research points to a structural change in the AMOC: the “shoaling” of its lower limb.

The AMOC can be visualized as a two-level system. A warm, upper current flows north near the surface, and a cold, deep current flows south far below. “Shoaling” means this deep, returning southbound current is becoming significantly shallower. Historically, this cold flow extended from approximately 1,000 to 4,000 meters deep. By the end of the 21st century, climate models project its lower boundary will shift upward to around 2,000 meters.

A shallower deep current is a warmer deep current, as it no longer plunges into the deepest, most frigid abyssal layers of the ocean. This change reduces the overall temperature difference between the warm water heading north and the “cooler” (but now less cold) water returning south. Because this temperature contrast is the primary driver of heat transport, a smaller difference makes the entire conveyor belt less efficient at moving heat poleward.

Our findings highlight an accelerated reduction in oceanic heat transport to the high‐latitude North Atlantic, with potential far‐reaching consequences for global weather and climate.

3. The Result: Fueling the North Atlantic “Warming Hole”

The weakening and shoaling of the AMOC are key contributors to a strange and tangible phenomenon known as the “warming hole”—a large patch of the subpolar North Atlantic that is cooling while the rest of the planet warms. This isn’t a coincidence; it’s part of a dangerous feedback loop.

The process works like this:

- The increasingly inefficient AMOC delivers less heat to the North Atlantic, causing sea surface temperatures in the region to fall, creating the warming hole.

- This patch of cooler ocean water sits under a rapidly warming atmosphere. Because the temperature difference between the sea and air is reduced, the ocean loses less of its heat to the atmosphere.

- This results in an “anomalous surface heat uptake,” where the ocean retains heat it would normally release. This retained warmth in the surface layers makes the water less dense, suppressing the critical sinking process that powers the AMOC engine in the first place, thus weakening it further.

In short, the structural change in the AMOC, the warming hole, and the altered heat exchange between the ocean and atmosphere are all tightly linked in a self-reinforcing cycle that accelerates the breakdown of this critical climate system. While this feedback loop accelerates the breakdown, the researchers note that the primary drivers of the AMOC’s weakening are external factors like surface freshening from melting ice and other complex heat and salt feedbacks.

Conclusion: A Deeper Change Than We Knew

The future of the Atlantic’s great ocean conveyor is not just a story of a simple slowdown. The evidence points to a more fundamental transformation in its vertical structure and its ability to do its job. The “shoaling” effect, a fundamental change in its vertical structure, is a critical accelerator. While the sheer slowdown in volume is the biggest factor, the source’s analysis reveals this structural change is responsible for an additional 30% of the total reduction in heat transport—a massive, previously underappreciated contribution.

While these findings are based on advanced climate models, the mechanism is consistent across multiple different simulations, strengthening the scientific confidence in this conclusion. The research reveals a new layer of complexity in how our climate system is responding to warming.

As we uncover how the ocean’s fundamental machinery is changing its very nature, what other hidden accelerators in our climate system are we yet to discover?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Lee, S.-K., Kim, D., Lopez, H., & Gomez, F. A. (2026). Future shoaling of the AMOC and its impact on oceanic heat transport to the subpolar North Atlantic. Geophysical Research Letters, 53, e2025GL119487. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL119487

Leave a comment