This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Volume, Heat, and Freshwater Divergences in the Subpolar North Atlantic Suggest the Nordic Seas as Key to the State of the Meridional Overturning Circulation” by Chafik and Rossby (2019).

Research by Chafik and Rossby identifies the Nordic Seas as the primary driver of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) due to massive heat loss and the creation of dense deep water. While the subpolar gyre experiences the largest decrease in water volume, the Nordic Seas release significantly more heat into the atmosphere than the subpolar and Labrador regions combined. The study utilizes specialized ADCP measurements from commercial vessels to quantify the movement of heat, salt, and water across the North Atlantic. Their findings suggest that existing climatological models often underestimate the actual amount of heat the ocean surrenders to the air in these northern reaches. Additionally, the data indicates that freshwater levels in the subpolar region are likely maintained by significant runoff from the Greenland shelf. Ultimately, the authors argue that the conversion of warm surface water to cold deep water in the Nordic Seas is the essential mechanism sustaining the entire circulation system.

4 Surprising Truths About the Currents That Shape Our Climate

The ocean has a “global conveyor belt” of currents that acts as our planet’s climate regulator. In the Atlantic, a critical part of this system is the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC), which carries warm water north, releases heat into the atmosphere, and sinks to flow back south—a process vital for moderating the climate of the Northern Hemisphere. For decades, scientists have studied this powerful system to understand its strength and stability.

However, new research is fundamentally challenging long-held assumptions about how this climate engine works. The findings suggest that the most critical processes—the very heart of this circulation—may not be happening where many have been looking. This article breaks down the four most surprising and impactful findings from a recent study that reframes our understanding of this crucial climate driver.

1. The engine room of the Atlantic isn’t where we thought it was.

For a long time, the Labrador Sea has been a major focus for scientists studying the “overturning” process, where warm surface waters cool, become dense, and sink. But new evidence points decisively elsewhere. The true key to the Atlantic MOC’s strength lies further northeast, in the Nordic Seas.

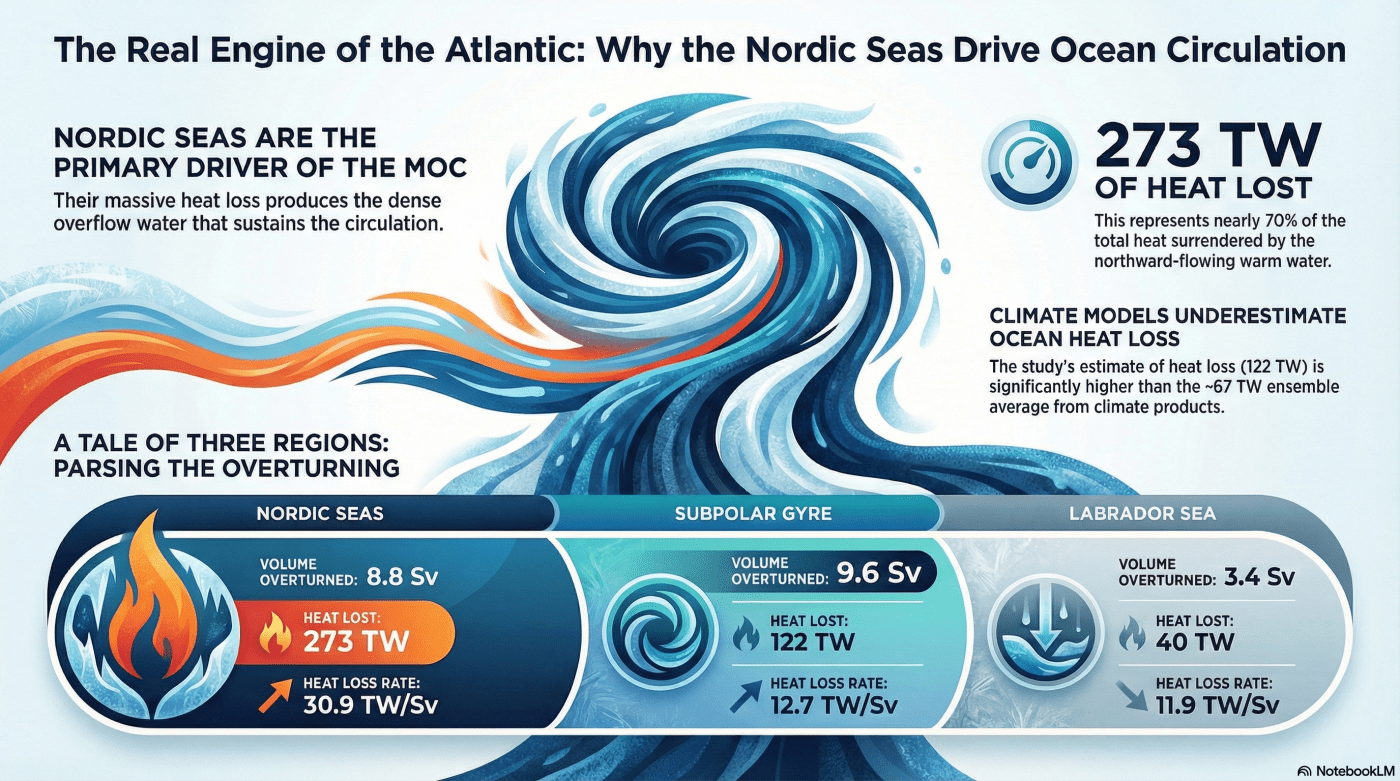

The research divides the transformation of warm water into three key regions. The Labrador Sea contributes about 3.4 Sverdrups (Sv, a unit of ocean transport) to the overturning. The vast subpolar gyre south of Iceland is where the largest volume of water, about 9.6 Sv, moves from the upper to the lower layer. But the critical factor for driving the entire circulation is the efficiency of heat loss, which creates the dense water that sinks.

Here, the Nordic Seas branch is the undisputed powerhouse. While it carries less volume than the subpolar gyre, the water flowing into the Nordic Seas sheds a staggering 273 Terawatts (TW) of heat. The study calculates the heat loss per unit of water for each region:

- Labrador Sea: 11.9 TW per Sv

- Subpolar Gyre: 12.7 TW per Sv

- Nordic Seas: 30.9 TW per Sv

The Nordic Seas are more than twice as efficient at releasing heat as any other region.

“in terms of heat loss the Nordic Seas, branch surrenders far more heat to the atmosphere than the other two combined. It thus plays the key role in maintaining a strong meridional overturning circulation.”

This geographical shift is a game-changer. It tells oceanographers that to truly understand the MOC’s stability in a warming world, we need to be looking closely at the processes occurring north of Iceland and Scotland.

2. The ocean is shedding heat faster than our climate models can see.

One of the study’s most startling conclusions came from a simple budget calculation. By measuring the heat carried by currents into the subpolar region and subtracting the heat carried out toward the Nordic Seas, the researchers determined how much heat must be lost to the atmosphere in between. Their estimate is a massive 122 TW.

When they compared this number to existing estimates, they found a major discrepancy. The average heat loss calculated from an ensemble of six different meteorological and observational products—our best tools for estimating air-sea heat exchange—was only about 67 TW.

This is a profoundly important finding. If the ocean is releasing nearly twice as much heat in this critical region as our models and data products suggest, we may be fundamentally underestimating a key component of the regional climate system. This finding is bolstered by other direct measurements of ocean currents, suggesting a consistent pattern: our best models may be missing a significant amount of heat escaping the North Atlantic. This gap has major implications for the accuracy of our climate models and our ability to project future climate change.

3. “Overturning” isn’t what it sounds like.

So, if the greatest heat loss is in the Nordic Seas, what is happening with that huge 9.6 Sv volume transfer in the subpolar gyre? The study reveals the process isn’t a dramatic plunge, but something far more subtle. The term “overturning” can conjure an image of a massive volume of water plunging into the deep ocean like a waterfall. The reality, at least for this largest portion of the MOC, is far more elegant.

The study describes how the 9.6 Sv of water moves from the upper to the lower limb of the MOC through a process called “lateral subduction.” Here’s how it works: The boundary between the warm, upper waters and the cold, deep waters is not flat. This boundary, defined by a specific density surface, sits about 1,000 meters deep in the eastern Atlantic but rises, or “shoals,” to near the surface in the west. As surface water circulates westward, it is progressively cooled by the atmosphere, causing it to slide gently across this rising, sloping boundary and into the deep layer without a dramatic vertical sinking event.

“It is the shoaling of the interface from east to west… rather than a descent or sinking of water that defines the ‘overturning’ of the MOC here.”

This detailed view gives us a more physically accurate picture of how the ocean’s massive heat engine actually works, replacing a simplified concept with a more precise understanding of the fluid dynamics at play.

4. A freshwater mystery points straight to Greenland’s melting ice.

When the scientists calculated a freshwater budget for the region, they found another puzzle. After accounting for all known water flows, they calculated a net loss of 0.09 Sv of freshwater from the region that needed to be balanced by an external source.

Precipitation adds about 0.02 Sv, but that still leaves a significant imbalance of 0.07 Sv unaccounted for. Where is this extra freshwater coming from? The authors conclude that there is only one plausible source: freshwater runoff from the Greenland shelf. This makes logical sense, as the Greenland ice sheet is melting at an accelerating rate.

However, the authors are careful to note that there is not yet “clear-cut observational support for this.” This doesn’t weaken the finding; instead, it frames an exciting and urgent scientific question. It highlights a critical gap in our observations and underscores the need for more research to track how melting ice from Greenland is influencing this vital ocean circulation system.

A New Map for a Changing Climate

This research provides a new map for understanding the Atlantic’s climate engine. It tells us the powerhouse is not where we thought, the processes are more nuanced than we imagined, and our tools may be underestimating key exchanges. Accurately understanding this system is not just an academic exercise—it is fundamental to predicting the future of our climate.

These findings leave us with a critical question to ponder: As the Arctic continues to warm and freshwater input from Greenland increases, how will the true engine of the Atlantic respond, and what will that mean for us all?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Chafik, L., & Rossby, T. (2019). Volume, heat, and freshwater divergences in the subpolar North Atlantic suggest the Nordic Seas as key to the state of the meridional overturning circulation. Geophysical Research Letters, 46, 4799–4808. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL082110

Leave a comment