This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by Google Gemini Pro and NotebookLM, provide a brief summary of the four primary “engines” of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) based on Pickart et al. (2003), Chafik & Rossby (2019),, Lozier et al. (2019), Zou et al. (2020), Petit et al. (2020), Chafik et al. (2022), Koman et al. (2022), and many other studies not listed here.

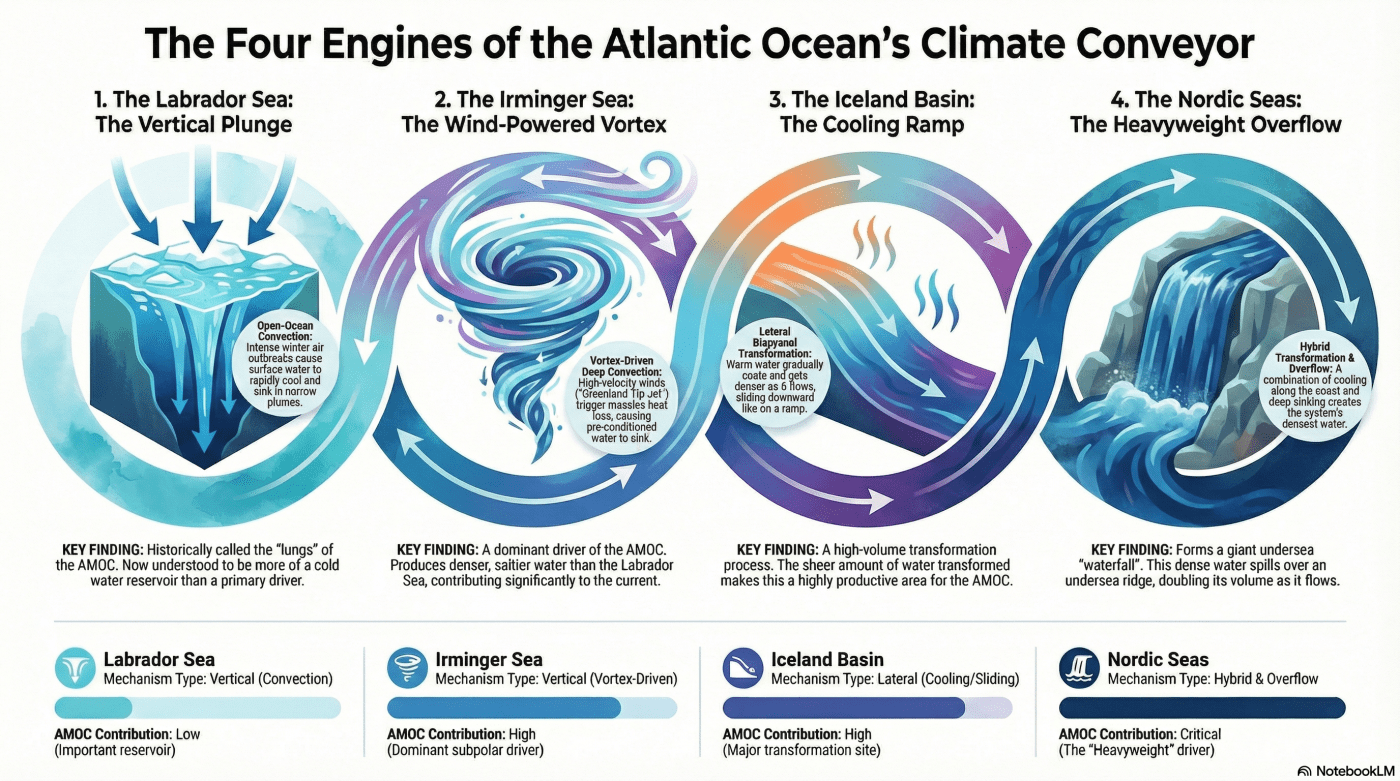

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, is often described as the ocean’s “global conveyor belt.” This immense system of currents transports heat from the tropics toward the poles, playing a critical role in regulating Earth’s climate. We’ve all seen the simplified diagrams showing warm water flowing north, sinking in the North Atlantic, and returning south as a cold, deep current. However, that simple picture hides a far more complex and fascinating reality. The process of “sinking” isn’t a single event in one location; it’s the work of several distinct and powerful “engines,” each operating with its own unique physics. The traditional understanding of how this conveyor belt is powered is being rewritten by modern ocean science. This short article summarizes four different engines that power this massive, climate-critical system.

1. The Labrador Sea: The Famous “Lungs” of the Atlantic Aren’t the Main Pump

Historically, the Labrador Sea was considered the “lungs” of the AMOC, but it is now understood to play a surprisingly different role. The mechanism here is known as “Open-Ocean Convection.” During winter, intensely cold air from North America blows over the sea, causing surface water to lose heat and buoyancy rapidly. This triggers violent vertical mixing in narrow “plumes,” only a few kilometers wide, that can plunge to depths of 2,000 meters.

The counter-intuitive discovery is that this dramatic process doesn’t actually drive the majority of the current. Recent science, particularly from the OSNAP (Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program), has revealed that the Labrador Sea Water (LSW) produced by this convection accounts for a relatively small portion of the AMOC’s deep-water transport (only ~2 Sv, or Sverdrups—a unit equal to one million cubic meters of water per second). This finding represents a major shift in scientific understanding. While the process produces a high volume of cold water, it has a low impact on driving the current, recasting the Labrador Sea as more of a “reservoir of cold, fresh water” than a primary pump.

While convection is intense, the OSNAP program has shown that LSW does not drive the bulk of the AMOC’s volume transport.

- Primary Mechanism: Open-Ocean Convection

- The Process: During intense winter outbreaks of cold continental air from North America, the surface water loses buoyancy rapidly. It sinks in narrow vertical “plumes” (only a few kilometers wide) that can reach depths of 2,000 meters.

- Key Output: Labrador Sea Water (LSW).

- Current Scientific View: While convection is intense, the OSNAP program has shown that LSW does not drive the bulk of the AMOC’s volume transport. It serves more as a reservoir of cold, fresh water than a primary pump for the global conveyor.

2. The Irminger Sea: A Jet Stream of Wind Triggers a Dominant Ocean Engine

East of Greenland lies the Irminger Sea, now recognized as a more significant engine of the AMOC. Its unique mechanism is directly tied to the atmosphere. A high-velocity wind event, known as the “Greenland Low-Level Tip Jet,” accelerates around the southern tip of Greenland and causes massive heat loss from the ocean surface below.

This cooling effect is amplified by the wind stress curl-driven circulation, which creates a “dome” that brings deep water closer to the surface. This “preconditions” the water, making it ready to sink easily and deeply the moment the Tip Jet cools it. Producing a denser class of water known as Irminger Sea Intermediate Water, this engine contributes a dominant ~8 Sv to the current. Note that only around 2 Sv out of ~ 8 Sv represents water that is pushed directly from the surface to depths of 1,000–1,500 meters. Even though the formation is only ~2 Sv, this water is so dense that it entrains (drags) an additional ~6 Sv of surrounding water as it sinks down the continental slope, which is why the “total contribution” looks much larger (~8 Sv). This demonstrates a direct and powerful link between a specific atmospheric phenomenon and the behavior of a massive ocean circulation system. Located east of Greenland, this region is now recognized as a more dominant driver of the AMOC than the Labrador Sea.

- Primary Mechanism: Vortex-Driven Deep Convection

- The Process: The “Greenland Tip Jet”—a high-velocity wind caused by air accelerating around Cape Farewell—triggers massive heat loss. Because the Irminger Sea has a cyclonic circulation that “domes” deep water toward the surface (preconditioning), the water sinks easily when cooled.

- Direct Sinking: This 2 Sv represents water that is pushed directly from the surface to depths of 1,000–1,500 meters.

- The “Multiplier”: Even though the formation is only ~2 Sv, this water is so dense that it entrains (drags) an additional ~6 Sv of surrounding water as it sinks down the continental slope, which is why the “total contribution” looks much larger (~8 Sv).

- Key Output: Irminger Sea Intermediate Water.

- Significance: It provides a denser, saltier class of water than the Labrador Sea, contributing more significantly to the lower limb of the AMOC.

3. The Iceland Basin: Some Engines are More Like “Cooling Ramps” than Elevators

The engine in the Iceland Basin works in a completely different way from the violent vertical mixing seen elsewhere. It operates less like a “vertical elevator” and more like a “cooling ramp.”

The process is called “Diapycnal Transformation.” Here, warm, salty water from the North Atlantic Current flows steadily northeast. As it travels, it constantly loses heat to the atmosphere, becoming gradually cooler and denser. Instead of plunging downwards in plumes, this water simply “slides” downward across density surfaces. The significance of this gentle but persistent process cannot be overstated; it is a high-volume transformation that produces Subpolar Mode Water, making the Iceland Basin one of the most productive areas for feeding the AMOC’s lower limb with a contribution of around 7.5 Sv. The Iceland Basin operates more like a “cooling ramp” than a “vertical elevator.”

- Primary Mechanism: Diapycnal Transformation (Lateral Subduction)

- The Process: Warm, salty water from the North Atlantic Current flows northeast. As it travels, it loses heat steadily to the atmosphere. Instead of plunging vertically in plumes, the water gradually increases in density and “slides” downward across density surfaces (i.e., isopycnals).

- Key Output: Subpolar Mode Water.

- Significance: This is a high-volume process. The sheer amount of water transformed here makes the Iceland Basin one of the most productive areas for the AMOC’s lower limb.

4. The Nordic Seas: The System’s “Heavyweight” is an Undersea Waterfall

The Nordic Seas are home to the most critical and powerful engine, providing the densest water in the entire system. Its mechanism is a hybrid: warm Atlantic water cools as it circles the basin, while in the center, vertical convection occurs where sea ice formation leaves behind extremely cold, salty water.

This incredibly dense water, called Nordic Sea Overflow Water (NSOW), pools behind the Greenland-Iceland-Scotland Ridge, a massive underwater mountain range. Eventually, it “spills over” the sills in the ridge, creating a giant undersea waterfall. The impact of this “Overflow” is immense. As the water cascades downwards, it “entrains”—drags along and mixes with—the surrounding water, effectively doubling its volume. This process contributes a powerful 6~9 Sv to the deep Atlantic.

Together, these distinct processes contribute nearly 20 Sverdrups of deep water, with the engines east of Greenland—in the Irminger, Iceland, and Nordic Seas—providing nearly 90% of the total volume. This is the northernmost reach of the AMOC and provides the densest water in the entire system.

- Primary Mechanism: Hybrid (Boundary Transformation + Convection).

- The Process: The Rim Current: Warm Atlantic water flows along the Norwegian coast, cooling and densifying as it circles the basin (Lateral).

- Greenland Sea Convection: In the center of the sea, vertical “chimneys” of water sink during ice formation (Vertical).

- The “Overflow”: All this dense water pools behind the Greenland-Iceland-Scotland Ridge. It eventually “spills over” the sills like a giant undersea waterfall.

- Key Output: Nordic Sea Overflow Water (NSOW).

- Significance: This is the densest component of the AMOC. As it spills over the ridge, it “entrains” (drags and mixes with) surrounding water, doubling its volume before it even reaches the deep Atlantic.

Comparative Summary: A Complex System with Big Questions

The Atlantic’s great conveyor belt is clearly not a single, simple pump. It is a complex and elegant interplay of at least four distinct and fascinating engines, each with its own physical mechanics, from vertical plumes and wind-driven vortexes to gradual cooling ramps and colossal undersea waterfalls. Understanding these individual components is vital to understanding the stability of the whole system.

This new, more nuanced picture raises critical questions for the future. As our climate changes, how will these different engines respond to warming air, melting ice, and shifting winds? And what could that mean for the stability of the global conveyor belt we all depend on?

| Region | Mechanism Type | Depth | AMOC Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labrador Sea | Vertical (Convection) | Very Deep (2000m+) | Low (High volume, low transport drive) ~2 Sv |

| Irminger Sea | Vertical (Tip-Jet driven) | Intermediate/Deep | High (Dominant subpolar driver) ~8 Sv (~2 Sv direct sinking & ~6 Sv entrainment of surrounding water) |

| Iceland Basin | Lateral (Cooling/Sliding) | Intermediate | High (Major transformation site) ~7.5 Sv (~6 Sv due to surface buoyancy loss & ~1.5 Sv subduction into dense overflow water) |

| Nordic Seas | Hybrid & Overflow | Deepest | Critical (The “Heavyweight” driver) 6.0-9.0 Sv |

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Chafik, L., & Rossby, T. (2019). Volume, heat, and freshwater divergences in the subpolar North Atlantic suggest the Nordic Seas as key to the state of the meridional overturning circulation. Geophysical Research Letters, 46, 4799–4808. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL082110

Chafik, L., Holliday, N. P., Bacon, S., & Rossby, T. (2022). Irminger Sea is the center of action for subpolar AMOC variability. Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL099133. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099133

Koman, G., Johns, W. E., Houk, A., Houpert, L., & Li, F. (2022). Circulation and overturning in the eastern North Atlantic subpolar gyre. Progress in oceanography, 208, 102884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2022.102884

Lozier M. S. et al. (2019). A sea change in our view of overturning in the subpolar North Atlantic. Science 363,516-521. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau6592

Petit, T., Lozier, M. S., Josey, S. A., & Cunningham, S. A. (2020). Atlantic deep water formation occurs primarily in the Iceland Basin and Irminger Sea by local buoyancy forcing. Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2020GL091028. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL091028

Pickart, R., Spall, M., Ribergaard, M. et al. (2003). Deep convection in the Irminger Sea forced by the Greenland tip jet. Nature, 424, 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01729

Zou, S., Lozier, M.S., Li, F. et al., 2020: Density-compensated overturning in the Labrador Sea. Nat. Geosci. 13, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0517-1

Leave a comment