This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “An outsized role for the Labrador Sea in the multidecadal variability of the Atlantic overturning circulation” by Yeager et al. (2021).

This research article by Yeager et al. (2021) utilizes high-resolution climate simulations to investigate the Labrador Sea’s influence on long-term changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). While recent short-term observations suggest the eastern subpolar gyre dominates ocean overturning, this study demonstrates that Labrador Sea buoyancy forcing remains a primary driver of multidecadal variability. The authors find that the production of dense Labrador Sea Water acts as a critical precursor to major fluctuations in the Atlantic’s circulation and heat transport. By resolving ocean mesoscale eddies, the model achieves a more realistic representation of deep-sea processes than previous low-resolution versions. Ultimately, the paper provides a uniquely credible framework for reconciling conflicting observational and modeling perspectives on North Atlantic climate dynamics.

1.0 Introduction: The Great Ocean Conveyor Belt and a Modern Scientific Mystery

The Atlantic Ocean is home to a powerful system of currents often called the “great ocean conveyor belt.” Officially known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), this massive network acts like a planetary-scale circulatory system, transporting warm surface water from the tropics northward and sending cold, dense deep water southward. By moving heat around the globe, the AMOC plays a fundamental role in shaping global climate patterns, and its variability is the primary dial controlling decadal changes in northbound heat flow—accounting for over 90% of that variance.

For decades, climate science was guided by a clear theory. Scientists theorized that frigid winter winds lashing the Labrador Sea, nestled between Canada and Greenland, created the super-dense, sinking water that powered this conveyor. Climate models consistently pointed to this sea as a key engine. But recently, a major international effort called the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP) presented a fundamental challenge to this understanding. Direct observations suggested the Labrador Sea’s role was “negligible” and that the real action was happening far to the east. This created a high-stakes disagreement between established models and real-world measurements, leaving scientists with a critical question: what is the true role of the Labrador Sea? A new, unprecedentedly high-resolution climate simulation now helps reconcile these two perspectives in a surprising way. Crucially, this model serves as a trustworthy referee because it has a realistic representation of key Atlantic phenomena, avoiding the biases—like excessive deep convection in the Labrador Sea—that plagued older models.

2.0 Takeaway 1: The Labrador Sea Isn’t the Main Engine, It’s the Pacemaker

The new, high-fidelity model confirms what the recent OSNAP observations showed: when looking at the average state of the ocean, the transformation of warm water into cold, dense deep water happens “predominately in the eastern subpolar gyre.” In this sense, the Labrador Sea is not the primary engine sustaining the steady, time-mean flow of the AMOC.

However, the model reveals a crucial twist. When scientists analyzed the simulation for multidecadal variability—the slow, rhythmic changes that occur over decades—they found that the Labrador Sea plays an “outsized role.” While it may not provide the bulk of the power for the conveyor belt’s average speed, it is the primary driver of its long-term fluctuations. The best analogy is a pacemaker: it doesn’t supply the heart’s main muscular power, but it sets the rhythm and pace of its beat over time.

3.0 Takeaway 2: It’s All About the “Vintage” of Seawater

The Labrador Sea’s powerful influence on long-term climate rhythms comes from the unique type of water it produces, not necessarily the total volume. The study shows that the sea is a primary source of a particularly dense water mass, which the researchers call “dense Labrador Sea Water” (dLSW)—the densest “vintage” of Labrador Sea Water.

Crucially, the multidecadal ebbs and flows of the AMOC are not driven by the total amount of water transformed, but by variations in the “vintage” of this specific water. In some periods, the Labrador Sea produces anomalously dense water; in others, it produces anomalously light water. It is this fluctuation in density—the changing vintage—that acts as the main lever controlling the AMOC’s strength over decades. The study’s authors powerfully summarize this counter-intuitive finding:

“The implication is that the tail wags the dog in the North Atlantic on multidecadal time scales: While the Labrador Sea contributes only marginally to the net WMT required to sustain the time mean Atlantic thermohaline circulation, it plays an outsized role in driving the LF variability of AMOC.”

4.0 Takeaway 3: The Ocean’s Deep, Slow Memory

The simulation reveals how events that begin deep within the Labrador Sea eventually ripple through the entire circulation system years later. This “bottom-up” mechanism highlights the ocean’s deep, slow memory. It reveals a startling truth: the climate we feel at the surface is, in part, a delayed reaction to silent, slow-moving events happening miles below in the ocean’s abyss.

The causal chain of events unfolds in a specific sequence:

- It begins with the anomalous production of super-dense water (dLSW) in the Labrador Sea due to surface cooling.

- This creates “thickness anomalies”—essentially, a buildup or thinning of this dense water layer—in the deep ocean.

- These deep ocean changes propagate slowly southward along the western boundary of the Atlantic. Years later, this buildup or thinning of the deep, dense water layer directly causes the sea surface height to fall or rise above it.

- Finally, these shifts create subtle slopes on the ocean’s surface that steer the massive, warm currents of the upper ocean, altering the path and strength of the AMOC’s “upper limb.”

The model identifies a distinct time lag in this process. Changes in the deep, southward-flowing waters lead the changes in the upper, northward-flowing part of the circulation by “several years,” with one analysis showing a clear “5-year delay.” This demonstrates how the deep ocean can store and then transmit the memory of past events, providing a key source of “decadal predictability” in our climate system.

5.0 Conclusion: A New Perspective on a Complex System

This new research provides a far more nuanced understanding of the Atlantic’s climate engine. The Labrador Sea, once thought to be either the main driver or largely irrelevant, is now understood to be a critical pacemaker. While it may not power the average circulation, its production of uniquely dense water governs the multidecadal rhythms of the entire AMOC system.

This new understanding shows how subtle processes in the deep ocean can have long-lasting effects on our climate system. As the planet warms, the crucial question remains: How will these sensitive deep-water formation sites respond, and what might that mean for the climate rhythms we depend on decades from now?

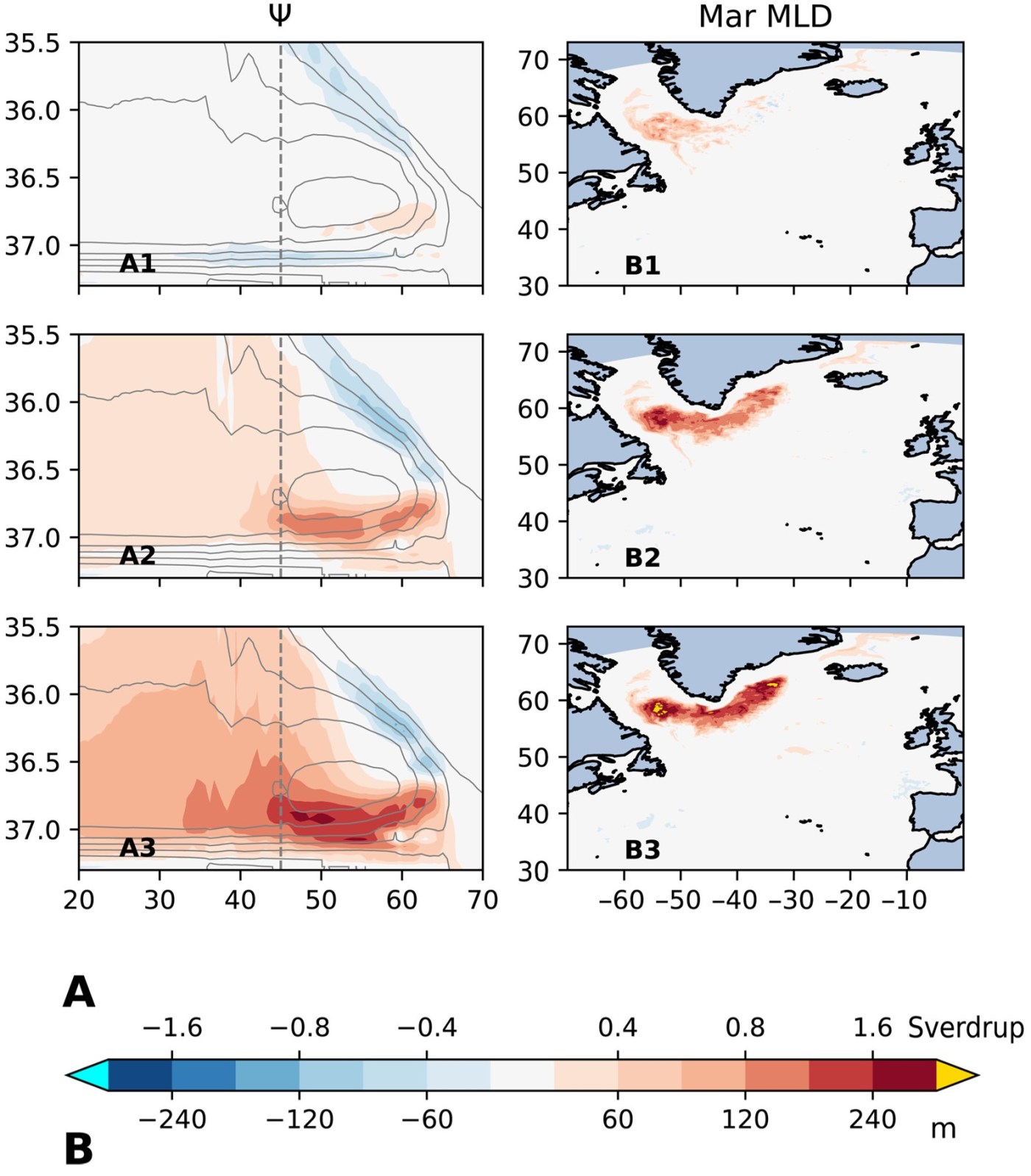

Fig. 7 from Yeager et al. (2021): This plot shows that a strong overturning at 45°N can be traced back to exceptional deep-convection activity in the Labrador Sea, 6 years prior to the peak. From High-Resolution CESM run, lag composite anomalies corresponding to anomalously strong Ψmax at 45°N (>+1σ). (A) Overturning stream function (Ψ) as a function of σ2 (y axis) and latitude (x axis). (B) March Mixed Layer Depth (MLD) which serves as a proxy for deep convection activity. Numbered rows correspond to lag time in years (A1-B1 for -6 year lag, A2-B2 for -4 year lag, and A3-B3 for -2 year lag), with Ψmax at 45°N lagging for negative values (i.e., time increases from top to bottom). The dashed line in (A) denotes 45°N. Note that the color fill interval doubles at large values. All fields were detrended and low-pass–filtered.

Yeager, S. et al. (2021). An outsized role for the Labrador Sea in the multidecadal variability of the Atlantic overturning circulation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh3592. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abh3592

Leave a comment