This blog post, created by NotebookLM, is based on “On the Atlantic extratropical-tropical teleconnection in response to external freshwater forcing” by Joshi an Zhang (2026).

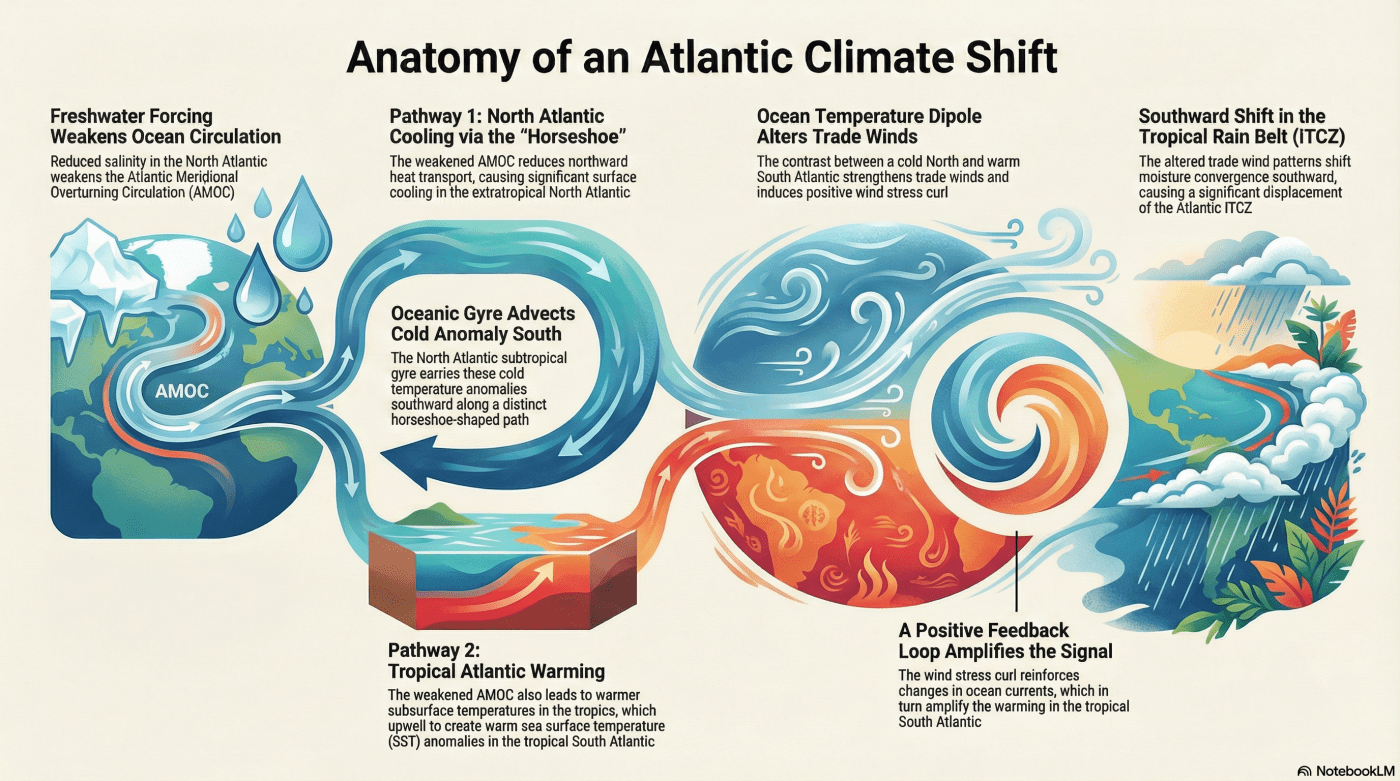

This research study utilizes a coupled climate model to investigate how a massive influx of freshwater in the North Atlantic triggers a chain reaction that shifts the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) southward. The authors demonstrate that a weakened Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) cools the North Atlantic and warms the South Atlantic, primarily through oceanic advection and gyre dynamics rather than atmospheric feedback alone. Cold anomalies propagate equatorward along a horseshoe pathway, driven by the slow movement of the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. Simultaneously, changes in western boundary currents and wind stress curl amplify warming in the tropical South Atlantic. These temperature shifts generate a dipole pattern that alters trade winds and moisture convergence, ultimately repositioning tropical rainfall belts. This process-based analysis suggests that many existing models likely underestimate these teleconnections due to biases in their representation of ocean currents and upwelling.

Three Surprising Ways a Weaker Atlantic “Conveyor Belt” Could Rewire Our Climate

Deep beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean flows a powerful current, a vast river often called the “great ocean conveyor belt.” Scientists know it as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), and it acts as the pulse of our planet’s climate system. By transporting immense amounts of heat from the tropics northward, it plays a crucial role in regulating global climate patterns.

There is growing concern that external freshwater forcing—primarily from melting ice sheets in the northern high latitudes—can weaken this critical circulation. A new climate model study from researchers Rajat Joshi and Rong Zhang reveals that the ripple effects of a weaker AMOC are far more complex and counter-intuitive than previously understood. Their analysis focuses on the boreal summer (the Northern Hemisphere’s summer), when the climatic consequences are most pronounced.

This article breaks down the three most surprising takeaways from their findings, shedding new light on how our climate system responds to change.

1. A Famous Cooling Pattern Isn’t Caused by What We Thought

Climate models consistently predict that as the AMOC weakens, a distinctive “horseshoe pattern” of unusually cold sea surface temperatures (SST) will form in the North Atlantic. Importantly, this isn’t just a model’s flight of fancy; this pattern is also evident in observed, real-world climate shifts associated with Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV).

For years, the popular explanation for how this cooling spreads southward was a fast-acting atmospheric process known as the Wind-Evaporation-SST (WES) feedback. The idea was that changes in wind and evaporation were the main drivers carrying the cold signal toward the tropics. However, this new research overturns that assumption. The study’s abstract states it plainly: “Our analysis reveals that the wind-evaporation-sea surface temperature (SST) feedback is not the primary mechanism.”

The actual driver is a much slower oceanic process: the southward advection (the physical carrying of water and its properties) of the cold and fresh water signal from the northern seas. This signal is transported by the massive North Atlantic subtropical gyre, a slow-moving, clockwise river of water whose eastern branch, flowing south along the coasts of Europe and Africa, follows the exact path of the horseshoe cooling pattern.

This is a profoundly significant finding. It forces a scientific shift in focus from fast atmospheric effects to the slower, decadal-scale memory of the ocean. It means the climate system doesn’t just react instantly; it remembers and transports these signals over vast distances and long timescales, a critical insight for improving long-term climate prediction.

2. The North Cools, But the Tropical South Warms

One of the most striking results is the emergence of a sharp temperature dipole. While the North Atlantic experiences the widespread horseshoe-shaped cooling, the tropical South Atlantic simultaneously undergoes significant warming, primarily concentrated in the central and eastern basin.

The oceanic mechanism behind this southern warming is a multi-step process. First, the weakened AMOC alters currents along the western edge of the tropical North Atlantic, leading to the formation of a warm layer of water deep below the surface. Then, during the boreal summer, this deep warmth is brought to the surface. This happens because the southern tropics are in their winter (austral winter), a season when the upper ocean is less stratified and strong, climatologically normal winds drive more turbulent mixing and upwelling. This seasonal condition is perfectly primed to pull the deep warm water to the surface, causing sea surface temperatures there to rise.

This counter-intuitive result is a powerful illustration of the climate system’s deeply interconnected nature. A single slowdown event in the far north triggers opposite temperature effects in different parts of the same ocean, driven by a combination of deep ocean changes and seasonal atmospheric conditions.

3. Vicious Cycles Amplify the Changes

The study reveals that the climate system doesn’t just react passively to a weaker AMOC; it contains powerful positive feedback loops that can amplify the initial changes. A positive feedback loop is a vicious cycle where an initial effect triggers a chain reaction that makes the original effect even stronger. The researchers identified two critical loops.

The first is a purely oceanic feedback directly triggered by the process described in the first section.

- The cold, fresh water advected south along the horseshoe pathway is less dense than the surrounding seawater. This lower density, dominated by the water’s freshness (low salinity), causes the sea surface to bulge slightly, creating positive sea surface height (SSH) anomalies.

- This change in ocean height strengthens the gyre’s eastern branch.

- This stronger current, in turn, enhances upwelling and ocean heat transport divergence in the region, which amplifies the very cooling that started the process.

The second is a coupled ocean-atmosphere feedback:

- The sea surface temperature dipole (cold north, warm south) creates a pressure gradient that alters the tropical trade winds.

- These wind changes produce positive surface wind stress curl anomalies over the tropical North Atlantic.

- This effect amplifies the very changes to the ocean’s western boundary current that helped create the temperature dipole in the first place, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

These findings show that the climate system contains built-in mechanisms that can actively accelerate and intensify its response to a trigger like massive freshwater input, cascading a regional change into a much larger event.

Conclusion: A Deeper Understanding for a Changing World

The research by Joshi and Zhang provides a more detailed, process-based understanding of how our climate functions, emphasizing that the ocean’s intricate circulation and its feedback loops are more central to driving major climate shifts than previously understood.

Crucially, their findings serve as a benchmark for the global climate models we rely on for future projections. The paper notes that many models struggle to accurately simulate these effects, often underestimating them due to persistent biases in key areas like the pathway of the North Atlantic Current or the intensity of eastern boundary upwelling. This research pinpoints the exact physical processes that models must capture to get the climate right, highlighting why improving these high-resolution details is essential for producing reliable predictions.

As the Earth continues to warm, what other hidden oceanic mechanisms might emerge to reshape the climate we depend on?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Joshi, R., & Zhang, R. (2025). On the Atlantic extratropical-tropical teleconnection in response to external freshwater forcing. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 371 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01253-z

Leave a comment