This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “North Atlantic ventilation change over the past three decades is potentially driven by climate change” by Guo et al. (2026).

A new study suggests that seawater in the North Atlantic is aging, a phenomenon that indicates a slowdown in ocean ventilation over the last thirty years. By measuring the concentrations of chemical tracers like CFC-12 and sulfur hexafluoride, the study determined how long water has been isolated from the surface. While regional areas like the Labrador Sea show significant natural variability due to natural weather and climate variability , the broader basin exhibits a persistent aging trend and rising oxygen utilization. The study integrated these real-world observations with seven different climate models, all of which point to a human-driven climate change signal rather than mere natural fluctuation. These findings are critical because a weakening ventilation system reduces the ocean’s ability to sequester carbon and heat, potentially accelerating global warming. Future projections under high-emission scenarios further suggest that this deep-ocean aging will intensify, threatening marine ecosystems through prolonged deoxygenation.

The North Atlantic’s Hidden Clock Is Ticking Slower, Signaling a Major Climate Shift

Deep beneath the stormy surface of the North Atlantic, a vital planetary pulse is slowing down. This isn’t a forecast; it’s an observation decades in the making, and it carries profound warnings for our climate future. The ocean acts as a powerful engine for Earth’s climate, with a vast circulatory system known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) that pulls immense amounts of heat and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into its depths. This process, called ventilation, is a planetary-scale breathing system that keeps our climate in balance.

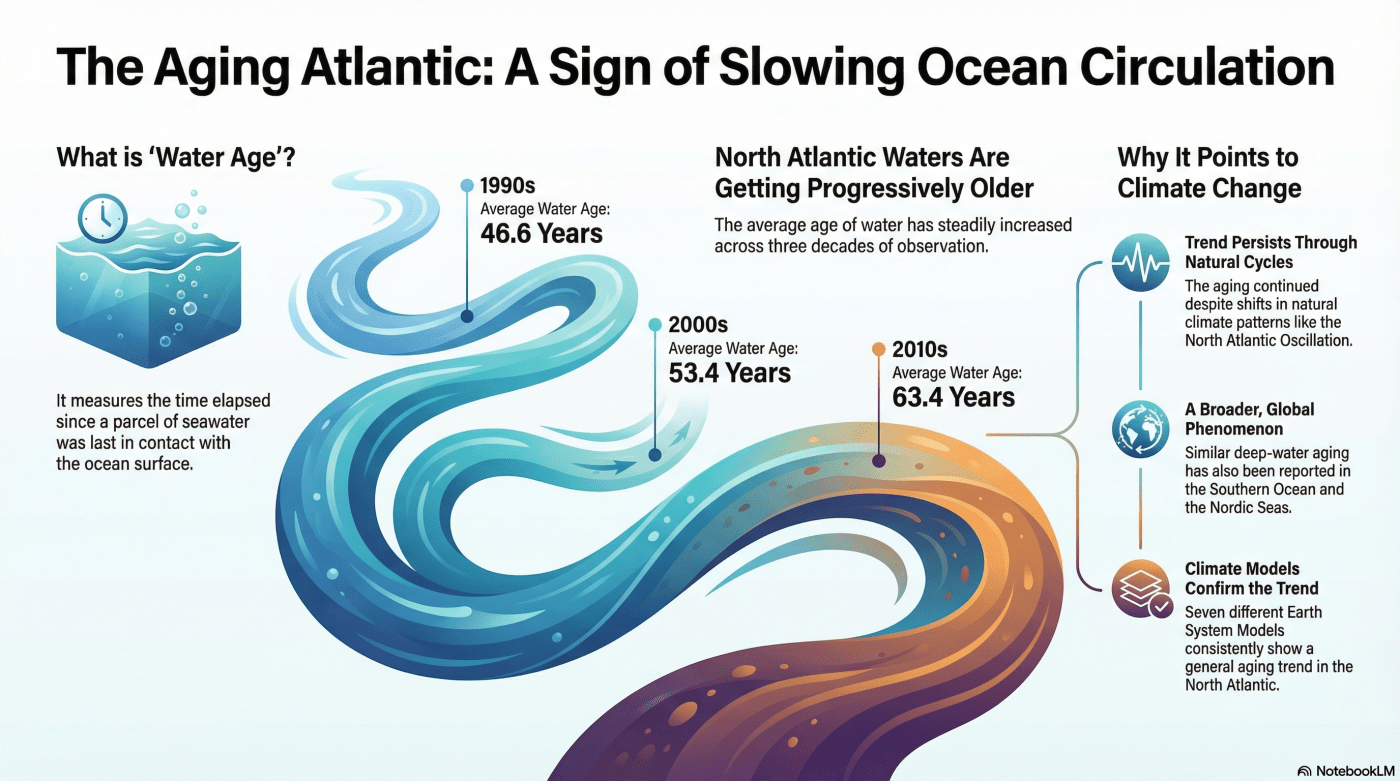

To gauge the health of this critical system, scientists are now looking at a novel metric: “water age.” This is a measure of how much time has passed since a parcel of seawater was last in contact with the atmosphere. It’s a hidden clock within the ocean that reveals how quickly or slowly its deep waters are being replenished.

A new study by Haichao Guo and a team of researchers has uncovered a surprising and concerning trend. By analyzing three decades of data, they found that across the vast expanse of the North Atlantic, the water is, on average, getting steadily older. This isn’t just a temporary fluctuation; it’s a persistent change that points directly to a slowdown in this critical climate-regulating system.

The Ocean Has an “Age”—And We’re Measuring It With Surprising Tools

The concept of “water age” provides a powerful way to understand ocean circulation. It quantifies the time elapsed since water left the surface, sinking into the ocean’s interior. A younger age means rapid, vigorous circulation and ventilation, while an older age signifies a more sluggish system that is less frequently in contact with the atmosphere.

To calculate this age, scientists use human-made chemicals called transient abiotic tracers. Specifically, they measure the concentrations of chlorofluorocarbon-12 (CFC-12)—an old refrigerant—and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). These gases dissolved into the ocean from the atmosphere over the past several decades, acting like a dye that slowly spreads through the deep ocean. By measuring their levels in a water sample, researchers can calculate how long that water has been isolated from the surface. This method is especially powerful because, unlike dissolved oxygen, these tracers are not affected by biological activity, ensuring that the “age” they reveal is a direct result of physical ocean ventilation.

The North Atlantic’s Waters Are Steadily Getting Older

The study’s primary finding is unambiguous: over the past three decades, the waters of the North Atlantic Ocean have been aging. This indicates a consistent slowdown in the ventilation process that is essential for its climate-regulating functions.

The data reveals a clear, quantifiable trend. From the 1990s to the 2000s, the volume-weighted mean water age across the basin increased by 5.5 years. The trend continued and accelerated in the following decade, with the water aging another 6.6 years from the 2000s to the 2010s. This aging is further supported by a parallel increase in Apparent Oxygen Utilization (AOU), which measures the oxygen ‘debt’ a water parcel has accumulated since it left the surface. A higher debt means a longer, more isolated journey in the deep.

This Isn’t Just a Natural Phase—It’s a Climate Change Signal

One of the biggest challenges in climate science is distinguishing long-term, human-driven trends from the ocean’s natural, cyclical fluctuations. The study’s authors accounted for the influence of major climate patterns like the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which is known to cause significant decadal variability. They found that the aging trend persisted regardless of the NAO’s phase. This meant that whether the Atlantic’s dominant atmospheric pattern was in a state that promoted mixing or one that suppressed it, the underlying aging trend continued its inexorable advance.

What makes this finding even more robust is that the basin-wide aging trend emerged despite significant regional fluctuations. In areas like the Labrador Sea, a hotspot for deep water formation, ventilation strength varied dramatically, with some water layers even getting younger at times. The fact that the overall North Atlantic still showed such a clear and consistent aging signal highlights the power of the underlying climate-driven force at work.

This conclusion is bolstered by seven different Earth System Models, which, when fed historical climate data, also simulated a general aging trend. Critically, however, every single model underestimated the observed rate of aging, suggesting the real-world situation may be progressing even faster than our best climate models predict. And this isn’t an isolated phenomenon. Similar aging trends have been reported in other key areas, including the deep waters of the Southern Ocean and the Nordic Sea, pointing to a globally coherent response to a changing climate.

An Aging Ocean Means a Weaker Climate Ally

An aging ocean is far more than a scientific curiosity; it has profound implications for the entire planet. Slower ventilation directly weakens the ocean’s ability to perform its most critical climate services. A more sluggish circulation means the North Atlantic is less effective at absorbing excess heat from the atmosphere and sequestering anthropogenic carbon in its depths. In short, as the ocean ages, it becomes a less effective buffer against climate change.

The consequences extend to marine life as well. Weaker ventilation leads to ocean deoxygenation, as deep waters are replenished with fresh oxygen from the surface less frequently. This decline in oxygen threatens the health and survival of marine ecosystems, creating vast regions that are less hospitable to life. The long-term nature of this change is perhaps the most sobering finding. The slowdown is not something that can be quickly reversed.

According to current models, the reduced ocean ventilation in the deep ocean is committed to continue for several hundred years, even if anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions are halted immediately or if atmospheric carbon dioxide levels recovered to the pre-industrial level.

A Slowdown We Can’t Ignore

The steady, persistent aging of the North Atlantic Ocean provides a robust new line of evidence showing how human-induced climate change is fundamentally altering our planet’s largest life-support systems. This is not a simulation of a potential future. The ocean’s aging is a measured reality, a logbook of change written over the past thirty years in the chemical composition of the water itself. The ocean’s internal clock is slowing down, and with it, its ability to protect us from the heat and carbon we are adding to the atmosphere.

As the ocean’s circulation slows and its memory of the surface grows longer, what other irreversible changes are we setting in motion for the centuries to come?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Guo, H., Koeve, W., Kriest, I. et al. North Atlantic ventilation change over the past three decades is potentially driven by climate change. Nat Commun 17, 200 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67923-x

Leave a comment