This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Emergence of the enhanced equatorial Atlantic warming as a fingerprint of global warming” by Dong et al. (2025).

Summary: This research identifies enhanced equatorial warming (EEW)—a pattern where sea surface temperatures near the equator rise faster than the surrounding tropics—as a definitive fingerprint of global warming. While long-term temperature changes in the Pacific remain inconsistent across models and observations, the equatorial Atlantic has shown a statistically significant warming trend since the 1950s. The study attributes this phenomenon primarily to greenhouse gas emissions, which cause a relaxation of equatorial trade winds. This atmospheric slowdown reduces the upwelling of cold subsurface water, allowing the Atlantic’s surface to heat more intensely at the equator. By utilizing CMIP6 climate models and historical data, the authors demonstrate that this localized warming is a robust response to a heating planet. Ultimately, these findings emphasize that meridional warming patterns are more reliable indicators of anthropogenic climate change than traditional longitudinal gradients.

A Clearer Fingerprint: Why the Atlantic Ocean Is Revealing a New Truth About Global Warming

For years, the scientific debate over ocean warming has been dominated by the tropical Pacific. Discussions about whether our planet is heading toward a future that looks more like El Niño or La Niña have filled headlines and research papers alike. But this focus has a persistent problem: significant discrepancies between what climate models predict and what satellites observe in the Pacific have created a fog of uncertainty, making it harder to project future climate with confidence.

This gap between models and reality is a major challenge for tracking how global warming is manifesting in our oceans. When our tools don’t align with the real world, it undermines our ability to anticipate the changes to come.

A recent study, however, has sliced through this statistical fog. By looking beyond the Pacific, scientists have identified a more robust and less ambiguous “fingerprint” of global warming in the oceans. This signal, called Enhanced Equatorial Warming (EEW), is providing a much clearer picture of climate change’s impact. This article breaks down the key takeaways from this pivotal discovery.

A More Reliable “Fingerprint” of Warming Has Been Identified

At the heart of this new understanding is a phenomenon called Enhanced Equatorial Warming (EEW). In simple terms, EEW occurs when the sea surface temperature in the narrow band around the equator (from 5°S to 5°N) warms faster than the temperature of the wider tropics (from 20°S to 20°N).

This signal is considered uniquely “robust” because climate models, which often diverge on regional predictions, show a remarkable level of agreement about it. An analysis of 36 leading climate models revealed deep disagreement on the future of the Pacific’s east-west temperature gradient—the very feature that defines El Niño-like patterns. In fact, only 3 of the 36 models showed a statistically significant trend for that specific Pacific gradient over the 1951-2020 period.

In stark contrast, an overwhelming majority of the models—more than three-quarters—converged on EEW as a consistent signature of global warming. This strong consensus makes EEW a far more reliable indicator for tracking the real-world impact of greenhouse gas warming on our tropical oceans.

The Signal is Already Clear and Detectable in the Atlantic

While climate models show EEW as a global phenomenon, the study found it has already emerged as a statistically significant trend in the real world—specifically in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The analysis, covering the period from 1951 to 2020, identifies the Atlantic as the basin where this fingerprint is most clearly visible and its cause best understood.

This presents a classic “signal versus noise” problem. The Pacific is an ocean where the “noise” of powerful natural cycles—like the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)—is so loud it drowns out the underlying “signal” of climate change in observational records. In the Atlantic, however, the EEW signal has finally become strong enough to be heard clearly above the background noise. This is backed by the models, which show the highest level of agreement (86%) for a positive EEW trend in the Atlantic.

Researchers attribute this trend directly to external forcings. Greenhouse gases are the primary driver of the Atlantic’s EEW, an effect that is partially offset by an opposing cooling influence from atmospheric aerosols.

The Cause is a Slowdown in Ocean “Stirring”

The physical mechanism behind the Atlantic’s EEW is a clear, cause-and-effect chain reaction revealed by a detailed heat budget analysis. It boils down to a slowdown in the ocean’s natural “stirring” process.

- Step 1: The equatorial trade winds blowing west across the Atlantic are weakening.

- Step 2: These winds are the primary engine for “equatorial upwelling”—a critical ocean process that pulls colder, deeper water up to the surface.

- Step 3: As the trade winds slow down, this upwelling process also weakens.

- Step 4: With less cold water being brought up from the depths to cool the surface, the equatorial region warms more rapidly than the surrounding tropical waters.

This sequence—weakening winds leading to reduced upwelling—is the key physical process that explains why the Enhanced Equatorial Warming fingerprint has emerged so clearly in the Atlantic.

This Wind Slowdown Is a Fundamental Response to Global Warming

The study confirms that the weakening of the Atlantic’s trade winds is not just a random fluctuation but a core consequence of a warmer planet. To prove this, scientists analyzed atmosphere-only experiments (AMIP simulations) that allowed them to isolate the effects of different types of warming.

Their first crucial finding came from simulating a spatially uniform warming of the entire ocean. Even in this simplified scenario, with no complex regional patterns, the tropical winds still weakened. This demonstrates that a slowdown of atmospheric circulation is a fundamental response to a warmer world, driven by basic energetic and hydrological constraints.

But the most powerful evidence came when they compared this to a patterned warming scenario, which included an El Niño-like warming pattern in the Pacific. They found that the wind slowdown over the Atlantic was actually smaller in this scenario. Why? Because the Pacific warming pattern tends to strengthen Atlantic trade winds, creating a regional effect that partially counteracts the fundamental global slowdown. The fact that the wind weakening is still detectable, even when another process is actively working against it, makes the finding even more profound. The signal is so robust it persists despite a competing effect trying to mask it.

A New Focus for Climate Science

The emergence of Enhanced Equatorial Warming in the Atlantic marks a potential paradigm shift in how we track climate change. For decades, climate science has been absorbed by the complex and often contradictory warming patterns of the Pacific. This new research suggests that the Atlantic may offer a clearer, more consistent, and already detectable signal of our planet’s response to rising greenhouse gas concentrations.

This discovery provides a vital new benchmark, moving the focus from a “noisy” basin to one where the fingerprint of global warming has become unambiguous. It validates a core prediction of climate models and confirms that a fundamental slowdown in tropical atmospheric circulation is not a distant forecast, but a present-day reality. This raises a critical question: If this clear signal is already here, what other profound changes to our planet’s weather, climate, and ecosystems is it foreshadowing?

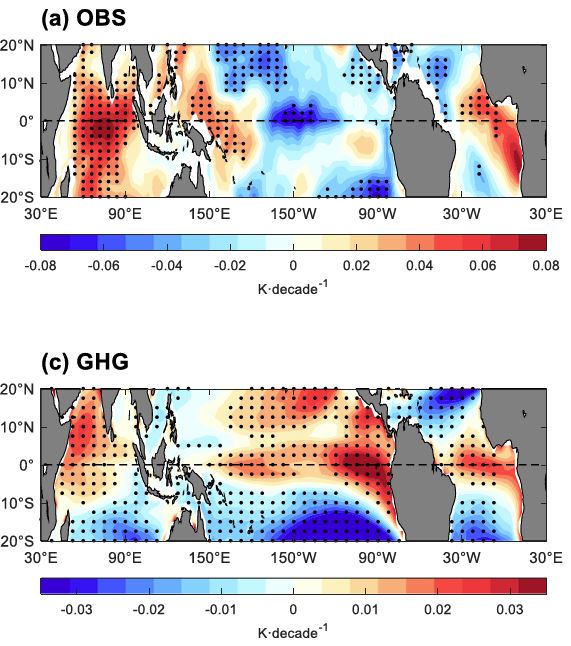

Supplementary Fig. 1 in Dong et al. (2025): The relative sea surface temperature (SST) trend patterns with the warming trend averaged over 20°S to 20°N removed at each grid during 1951-2020 from (a) observations (OBS) (HadISST 30 v1.1, ERSST v5 and COBE-SST 2), (c) greenhouse gas (GHG) only forcing runs based on 10 CMIP6 models. Stippling indicates the regions where the regression is statistically significant at the 95% level of confidence based on Student’s t-test. Units: K per decade.

Dong, L., Wang, Z., Wu, L. et al. Emergence of the enhanced equatorial Atlantic warming as a fingerprint of global warming. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68015-6

Leave a comment