This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Irminger Sea Is the Center of Action for Subpolar AMOC Variability” by Chafik et al. (2022).

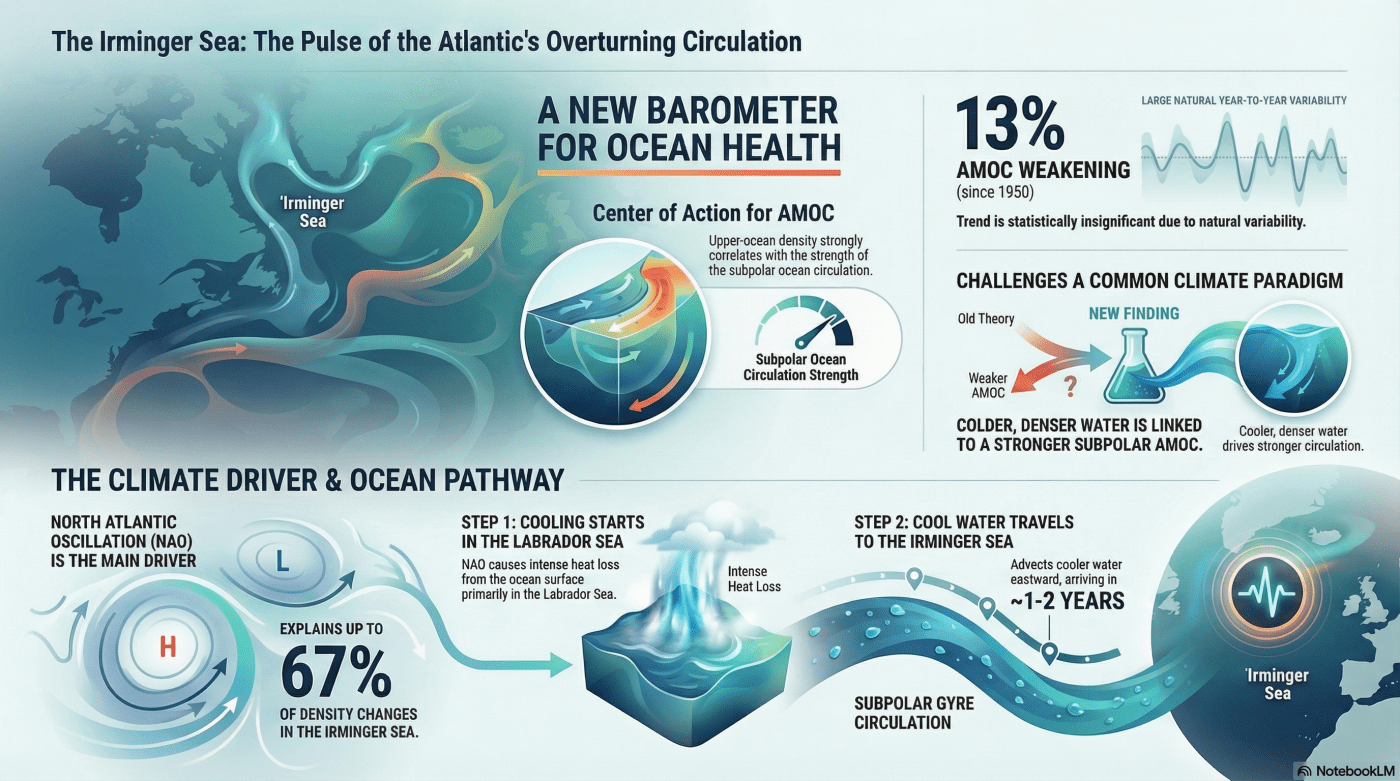

Summary: Chafik et al. (2022) identified the Irminger Sea as the primary “center of action” for driving fluctuations in the subpolar Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). By analyzing direct observations from the OSNAP array and long-term ocean reanalysis, the study demonstrated that upper-ocean density and sea-surface height in this region serve as reliable indicators of the current’s strength. The study reveals that water initially cooled in the Labrador Sea is transported into the Irminger Sea via the subpolar gyre, a process largely dictated by the North Atlantic Oscillation. While historical data since 1950 hints at a 13% weakening of the circulation, the researchers conclude this trend is not yet statistically significant due to high natural variability. Ultimately, the findings challenge existing climate paradigms by proving that colder, denser conditions actually coincide with a more robust subpolar overturning rather than a slowing one.

What a Small Patch of Ocean Near Greenland Is Telling Us About the Gulf Stream’s Health

1.0 Introduction: The Ocean’s Hidden Engine

The Atlantic Ocean is home to a vast and powerful system of currents known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Often called the Gulf Stream system, this planetary-scale “engine” plays a critical role in regulating our climate by transporting enormous amounts of heat from the tropics toward the poles. Its steady rhythm helps to shape weather patterns, sea levels, and ecosystems on both sides of the Atlantic.

Despite its global importance, this massive system is largely hidden from us, operating deep beneath the waves. Scientists have been working for decades to understand its complex mechanics and, crucially, to determine how it might be changing in a warming world. Direct, continuous monitoring is still relatively new, and many of our assumptions have been based on indirect measurements.

Recent research, however, has revealed some surprising truths that challenge long-held ideas about how this system works and where its most vital signs are found. This article explores three of the most impactful and counter-intuitive takeaways from a recent study that is changing how we monitor the health of the Atlantic’s hidden engine.

2.0 Takeaway 1: The Real “Center of Action” Isn’t Where We Thought

For a long time, scientists have focused on the Labrador Sea, a region west of Greenland, as a primary driver of the AMOC. This is where the ocean loses a tremendous amount of heat to the cold winter atmosphere, causing surface water to become colder, saltier, and denser, allowing it to sink and drive the deep, overturning flow.

However, a surprising new finding shows that while the Labrador Sea is where the most intense cooling happens, the most reliable signal for the AMOC’s strength is actually found in the Irminger Sea, a smaller region to the east of Greenland. The study reveals that the North Atlantic Oscillation (a major atmospheric pattern) drives the intense cooling in the Labrador Sea. Instead, they are carried eastward by the large, rotating subpolar gyre. This journey, which takes about a year, transports these ‘pre-conditioned’ waters to the Irminger Sea, where their density ultimately has the greatest impact on the strength of the overturning circulation.

This discovery is significant because it refines our understanding of where to look for the most critical signals of change in this massive climate system. It’s like discovering the true control panel for a complex machine isn’t the biggest, loudest part, but a more subtle and remote component.

A surprising finding is that density changes in the subpolar Irminger Sea, which explains most of the variability of the overturning between Greenland and Scotland, do not coincide with the region of the largest heat losses that are instead found in the Labrador Sea.

3.0 Takeaway 2: Colder and Denser Can Mean Stronger, Not Weaker

One of the most counter-intuitive findings from the research turns a common scientific assumption on its head. Direct observations show that periods of a stronger subpolar AMOC actually coincide with colder and denser conditions in the upper ocean of the Irminger Sea.

This represents a major reversal of a long-standing paradigm. Many previous studies, including those analyzing ancient climate records (paleoclimate studies), operated on the assumption that a cold North Atlantic was a clear signal of a weakening AMOC. The logic was that a slowdown in the heat-transporting current would naturally lead to cooling in the region. The new data, based on direct measurements of the circulation, challenges this interpretation directly.

This finding forces a re-evaluation of how we interpret both past and present climate signals. A “cold blob” appearing in the North Atlantic might not be the simple indicator of a slowdown that it was once thought to be. It could, under certain conditions, be associated with a more vigorous circulation.

“Our finding that, on decadal timescales, cold dense upper ocean is associated with strong subpolar AMOC indeed challenges the common paradigm from modern and paleo studies that cold sea-surface temperatures in the North Atlantic are associated with a weakening overturning.”

This paradigm shift is possible because, as the first takeaway showed, the initial cooling and the ultimate impact on the circulation are separated by a year-long journey across the subpolar gyre, complicating any simple, direct link between temperature and strength.

4.0 Takeaway 3: The Slowdown Story Is More Complicated Than We Thought

This brings us to the big question: Is the AMOC slowing down? The popular narrative, backed by some proxy-based studies, has been one of a significant, human-caused weakening.

Using their newly identified link between Irminger Sea density and AMOC strength, the researchers reconstructed the circulation’s variability back to 1950. Their analysis does suggest a potential long-term weakening of about 2.2 Sv (Sverdrups, a unit of ocean current volume), or roughly 13%, since the mid-twentieth century.

However, this finding comes with a critical scientific caveat: the trend is statistically insignificant. In simple terms, this means that the natural ups and downs of the system—the year-to-year and decade-to-decade swings—are so large that they completely obscure any potential long-term trend. We cannot yet say with confidence whether the observed decline is a real, long-term change driven by global warming or if it’s just part of the system’s natural, noisy behavior. This finding aligns with several other recent, independent studies that have also failed to find a clear long-term slowdown, reinforcing the conclusion that there is “no consensus… yet reached regarding basin-wide North Atlantic slowdown of the overturning circulation.”

5.0 Conclusion: A New Lens on Our Climate’s Future

Our understanding of the massive and complex AMOC system is constantly evolving. This research provides a powerful new proxy—the density of the water in the Irminger Sea—to more accurately monitor the health of this vital climate regulator. By identifying the true “center of action” and challenging old assumptions, scientists are better equipped to distinguish between natural variability and potential long-term change.

The work underscores the immense difficulty in detecting a clear, unambiguous signal of climate change within a system defined by powerful natural cycles. As scientists refine their tools for listening to these hidden ocean signals, what other fundamental assumptions about our planet’s climate might be turned on their head?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Chafik, L., Holliday, N. P., Bacon, S., & Rossby, T. (2022). Irminger Sea is the center of action for subpolar AMOC variability. Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL099133. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099133

Leave a comment