This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Human-induced changes in the global meridional overturning circulation are emerging from the Southern Ocean” by Lee et al. (2023).

For decades, the story of the ocean’s circulation in a warming world seemed straightforward. We have a clear picture of the “Global Conveyor Belt”—a massive system of currents formally known as the Global Meridional Overturning Circulation (GMOC)—that transports heat, nutrients, and carbon around the planet, regulating our climate. The common narrative, backed by many climate models, is that this critical system is undergoing a gentle slowdown due to human activity.

But this slowdown is only a fraction of a much more complex and revolutionary story. A recent study, grounded in decades of historical ocean observations, reveals that the conventional narrative has missed the main event. Instead of a simple weakening, the planet’s circulatory system is experiencing a violent push-pull reshaping, with the most dramatic, human-induced changes emerging from the one place most of us weren’t looking: the vast, turbulent Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica.

The planet’s circulatory system isn’t just flagging; it’s undergoing a profound reorganization, with two massive currents moving in opposite directions—one speeding up while the other clogs. This is radically altering the ocean’s fundamental structure from the bottom of the world up.

The Biggest Changes Are Happening Around Antarctica, Not the North Atlantic

While much scientific and public focus has centered on the Atlantic Ocean, this new research shows that the most significant and unambiguous human fingerprints on global ocean circulation are currently emerging from the Southern Ocean. By feeding decades of observational data into a state-of-the-art ocean model, the scientists could essentially rewind the tape on global circulation. The results pointed to an unambiguous epicenter of change.

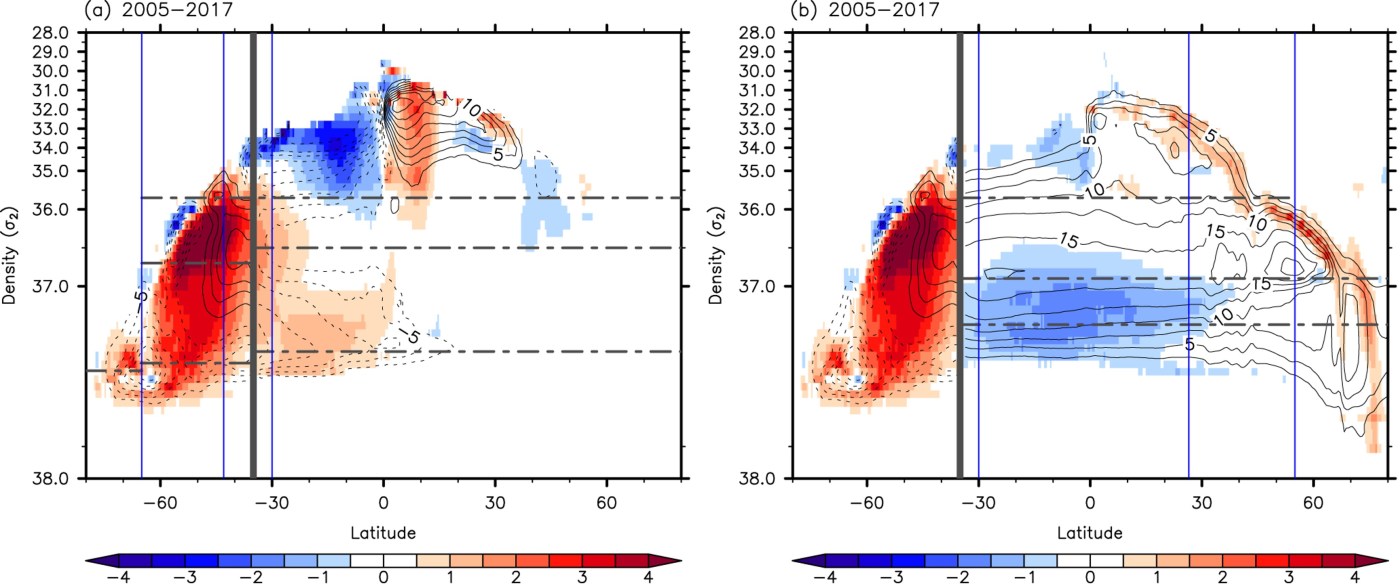

What they found was the beginning of a fundamental reshaping of the ocean’s heat and carbon plumbing. This involves a dramatic reorganization of two major “overturning cells”—one near the surface and one in the deep ocean. Since the mid-1970s, the upper cell has strengthened, expanded poleward, and pushed deeper into denser water layers. At the same time, the deep cell has weakened and contracted. This powerful realignment around Antarctica is the primary engine of change now rippling through the world’s oceans.

Part of the Conveyor Belt Is Actually Speeding Up

In a surprising twist that runs contrary to the “global slowdown” narrative, the study found that the upper overturning cell in the Southern Ocean has significantly strengthened. Since the mid-1970s, its transport has increased by an estimated 3 to 4 Sverdrups (Sv)—a unit of measure for ocean currents, where one Sverdrup is equivalent to a flow of one million cubic meters per second.

This acceleration is driven by a powerful “push-pull” mechanism directly linked to human activity:

- The Push: Stronger westerly winds circling Antarctica. These winds have intensified due to two major human impacts: the depletion of the ozone layer in the Southern Hemisphere’s stratosphere and the overall increase in atmospheric CO2.

- The Pull: The stronger winds enhance evaporation in the sub-Antarctic region. This makes the surface water saltier, and therefore denser. This denser water sinks more readily, pulling more water into the circulation to replace it and accelerating the upper cell.

Melting Ice Is Slowing the Deepest Current

In stark contrast to the accelerating upper cell, the lower overturning cell—the one that feeds the deepest, coldest parts of the global ocean—has weakened by a similar amount of 3 to 4 Sv and contracted over the same period.

The primary cause for this deep-ocean slowdown is the increasing flow of freshwater into the ocean from melting Antarctic ice shelves. This meltwater, driven by rising CO2 levels, creates a fresher, less dense layer on the ocean’s surface. This acts like a lid, preventing the extremely cold, salty surface water from becoming dense enough to sink. This process inhibits the formation of Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), the super-dense water mass that acts as the “drain” for the global conveyor belt, feeding its deepest pathways.

A “Readjustment” Is Now Reaching the Atlantic

For decades, the variability observed in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has been largely dominated by natural, cyclical patterns, particularly the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). This natural noise has made it difficult to isolate a clear, long-term, human-forced trend.

However, the new study reveals an emerging signal that cannot be explained by these natural cycles. In the most recent decade analyzed (2005-2017), researchers observed a distinct reduction in the southward flow of the deepest Atlantic water, known as Lower North Atlantic Deep Water (LNADW). This is not a vague ripple effect; it is a direct, physical consequence of the Southern Ocean’s transformation. The study’s key insight reveals that this very LNADW from the Atlantic flows south to become the primary source of water feeding the lower overturning cell in the Southern Ocean.

With the Southern Ocean’s deep “drain” now clogged by Antarctic meltwater, the entire system is starting to back up. This is likely the beginning of a “large-scale readjustment” of the Atlantic’s circulation, where massive changes at the bottom of the world are beginning to reconfigure the Atlantic’s structure from the abyss upwards.

A Global Reshaping Is Underway

The Global Meridional Overturning Circulation is not just weakening; it is undergoing a profound and complex realignment. The new evidence firmly establishes the Southern Ocean as the primary engine of human-induced change, where a strengthening upper current and a weakening deep current are fundamentally reshaping the global system. This is not a distant, future projection; it is a measured, ongoing transformation of the planetary system that has been unfolding, largely undetected, for nearly half a century.

This research marks a pivotal moment in our understanding of how humanity is impacting the planet’s largest and most critical climate regulator. As the authors of the study state, this is a clear and observable shift that is already in progress and expanding globally.

“This is the first study to report based on historical global hydrographic observations that a significant reshaping of the GMOC has already emerged from the Southern Ocean due to human activity, and is actively advancing into the other ocean basins.”

This leaves us with a critical question. As the planet’s circulatory system fundamentally reorganizes, what unforeseen consequences might this have for global climate, sea levels, and marine ecosystems in the decades to come?

Reproduced from Figures 1 & 2 in Lee et al. (2023): The GMOC volume transport streamfunction (contours) (a) in the Southern Ocean (south of 35°S) and the Indo-Pacific Ocean (north of 35°S), and (b) in the Southern Ocean (south of 35°S) and the Atlantic Ocean (north of 35°S) and its changes (shades) during a 2005–2007 in reference to the base period of 1955–1974. The vertical axis is potential density in reference to 2000 m (σ2 units). Black-dotted lines indicate the density ranges of water masses. Volume transports are in Sv units.

Lee, SK., Lumpkin, R., Gomez, F. Yeager, S., Lopez, H., Takglis, F., Dong, S., Aguiar, W., Kim, D. & Baringer, M. (2023). Human-induced changes in the global meridional overturning circulation are emerging from the Southern Ocean. Commun Earth Environ 4, 69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00727-3

Leave a comment