This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast on a paper “Tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillations” by Bao et al. (2025) was created by NotebookLM.

Deep Dive Podcast “Earth’s Global Climate Heartbeat The TWISO Cycle” powered by NotebookLM:

1.0 Introduction: The Stable Tropics Aren’t So Stable

When we think about the climate of the tropics, we tend to picture two extremes. On one hand, there are the immense, slow-moving patterns like the Hadley and Walker circulations—the planet’s great atmospheric conveyor belts that shift gradually with the seasons or over multiple years during events like El Niño. On the other hand, there’s the daily, chaotic churn of regional weather: thunderstorms that pop up and dissipate in a matter of hours. The vast space between these timescales was thought to be relatively quiet on a tropics-wide scale.

Recent research, however, has uncovered something extraordinary that challenges this view. Scientists analyzing decades of satellite and climate data have identified a surprisingly fast, system-wide “pulse” that synchronizes the entire tropical belt in a predictable rhythm. This newly identified phenomenon, named the Tropics-Wide Intraseasonal Oscillation (TWISO), reveals that the entire tropical climate system breathes in and out together on a cycle of roughly 30 to 60 days. It’s a discovery that adds a new, fundamental beat to the complex symphony of our planet’s climate.

2.0 Takeaway 1: The Tropics Have a Hidden 30-to-60-Day ‘Heartbeat’

By analyzing daily data from across the tropical region (30°N to 30°S), scientists found a clear and regular oscillation that was previously overlooked. Contrary to the expectation that tropical-mean variables would change smoothly over long periods, the data showed pronounced peaks of activity every 30 to 60 days.

This consistent rhythm isn’t just a minor fluctuation; it’s a powerful signal visible across multiple key indicators of the climate system. The oscillation appears in air temperature high in the atmosphere, in the temperature of the sea surface, and even in the net radiation escaping from the top of the Earth’s atmosphere. The fact that this pulse is detectable even when averaging data across the entire tropics highlights a remarkable, system-wide response. This finding fundamentally challenges the conventional view that the large-scale tropical circulation is stable on these shorter, sub-seasonal timescales.

As the researchers state in the significance section of their paper:

Tropical climate variability is shaped by a range of oscillations, but most known modes influencing the tropical mean state occur on seasonal or interannual timescales. Here, we identify a pronounced tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillation (TWISO) with a 30 to 60-days period, evident in satellite observations and reanalysis data.

3.0 Takeaway 2: This Rhythm Is More Fundamental Than the Famous MJO

For decades, climate scientists have known about the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), a major fluctuation of tropical weather that travels eastward around the globe every 30 to 60 days. As the “leading mode of intraseasonal variability in the tropics,” the MJO is famous for influencing weather patterns, from monsoons in India to hurricane formation in the Atlantic. So, is this new TWISO just another name for the MJO?

The surprising answer is no. The research reveals that while the MJO and TWISO are linked and can amplify each other, the MJO is not necessary for the TWISO to occur. The TWISO appears to be a more fundamental feature of the climate system.

An analogy helps to clarify this: think of the TWISO as the fundamental drumbeat of the tropical climate system. The MJO is like an additional, more complex rhythm that can play on top of it, sometimes making the overall beat stronger and more pronounced. But even when the MJO’s rhythm fades and the MJO is inactive, the underlying 30-to-60-day drumbeat of the TWISO continues. This suggests that the TWISO arises from more fundamental internal climate feedbacks among convection, radiation, and the surface fluxes between the ocean and atmosphere.

4.0 Takeaway 3: The Entire Tropical System Breathes in Sync

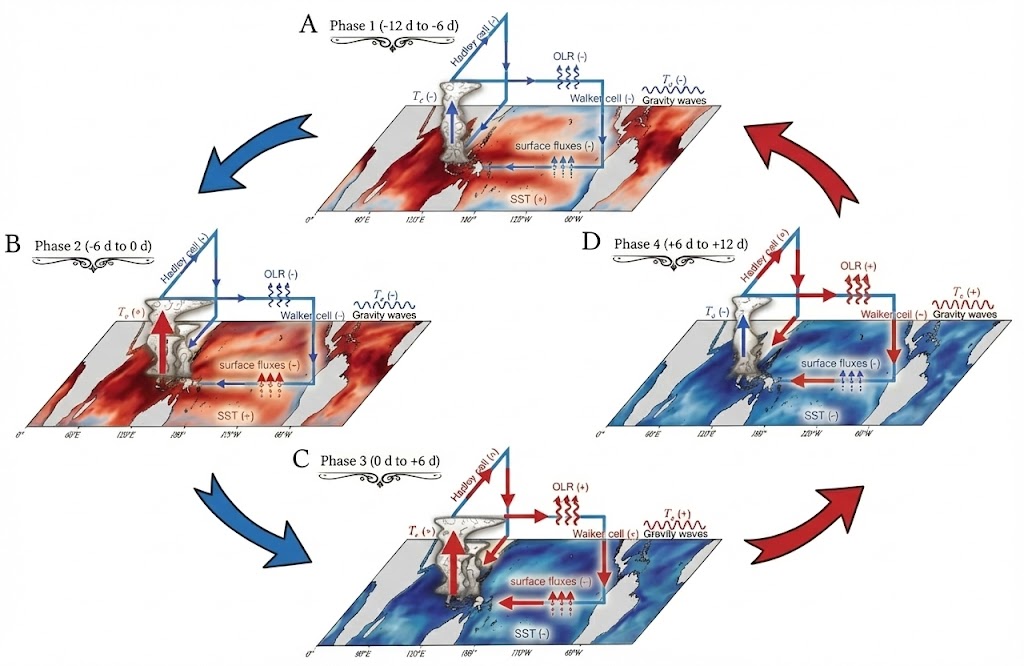

The TWISO is not just a localized event; it is a coordinated, cyclical dance that spans the entire tropical belt. The oscillation primarily originates with clusters of thunderstorms (convective perturbations) over the vast, warm waters of the Indo-Pacific, often called the “warm pool.”

When a warming event begins in the atmosphere over this region, it doesn’t stay there. The energy propagates outward in a dynamic wave. An initial warm perturbation first emerges over the Maritime Continent. From there, it spreads rapidly via fast-moving atmospheric gravity waves, extending across the entire tropical Pacific within about six days. Continuing its expansion, this wave of warmth covers the entire tropical belt within about 12 days.

This atmospheric warming is coupled with a strengthening of the major tropical circulations—the Hadley and Walker cells—and a corresponding increase in surface wind speeds. This remarkable interconnectedness shows how a pulse of thunderstorm activity in one part of the world can cause the entire tropical climate engine to respond in a synchronized and predictable cycle.

5.0 Takeaway 4: The Climate’s Engine Has a Built-In ‘Brake’

So, what drives this 30-to-60-day cycle? The oscillation is powered by a delicate and self-regulating feedback loop involving the exchange of heat between the warm ocean and the air above it, known as surface heat fluxes.

The cycle works like this:

- The Engine Starts: A large temperature and moisture difference between the warm ocean and the cooler air above it drives intense heat flux into the atmosphere. This energy transfer kicks off convection (thunderstorms) and strengthens surface winds.

- The Brake Engages: However, these stronger winds have two opposing effects. While they enhance evaporation (which feeds the atmosphere), they also simultaneously cool the sea surface and moisten the air right above it.

- The Cycle Reverses: This cooling and moistening effect reduces the energy difference between the ocean and the air. This reduction acts as a “brake,” eventually weakening the heat flux. With less energy being transferred, convection weakens, the large-scale circulation slows, and the cycle reverses back toward a cooler atmosphere and weaker winds, ready to begin again.

One of the most counter-intuitive findings is that the changes in these surface heat fluxes actually precede the changes in wind speed. This indicates that the energy exchange between the ocean and atmosphere is a critical driver of the cycle, not just a passive response to the winds.

6.0 Conclusion: Why This Hidden Pulse Matters

The discovery of the Tropics-Wide Intraseasonal Oscillation reveals a new layer of organized, predictable behavior in a climate system we thought we largely understood. This isn’t just an academic curiosity; it has significant practical implications. Understanding this fundamental rhythm could enhance our ability to predict weather on sub-seasonal timescales—the difficult forecast range between short-term weather and long-term climate.

Furthermore, by causing the system to oscillate far from its average state, the TWISO may help explain the likelihood of extreme weather events. Its influence on the Earth’s overall energy balance could also mean that it affects exchanges with the extratropics, potentially impacting global weather and climate patterns. This discovery opens up new avenues of research and challenges climate models to accurately represent this fundamental planetary pulse.

As we uncover these fundamental rhythms of our planet, how might it change our ability to predict, and perhaps prepare for, its future?

Modified from Figure 7 in Bao et al. (2025): Schematic of TWISO. (A-D) describe the tropical climate response during the four phases of TWISO. Red (blue) colors indicate that the corresponding processes have positive (negative) perturbations. Tc and Te represent atmospheric temperature near convection and the environment temperature respectively. Note that MJO is not shown in this schematic because it is not a necessary condition for TWISO to occur. However, when MJO is active, TWISO occurs with enhanced amplitude.

Bao, J., S. Bony, D. Takasuka, & C. Muller. (2025). Tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillations, Proceeding of National Academy of Science. U.S.A. 122 (48) e2511549122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2511549122

Leave a comment