This blog post and the “Debate” podcast on a paper “Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation slowdown suppresses Atlantic Niño variability” by Freire-SouzaLi et al. (2025) was created by NotebookLM.

Debate Podcast: This is different from Deep Dive Podcast. This is a debate between two hosts, illuminating different perspectives on the study, “Meltwater or Warming Drives Atlantic Niño Collapse” powered by NotebookLM:

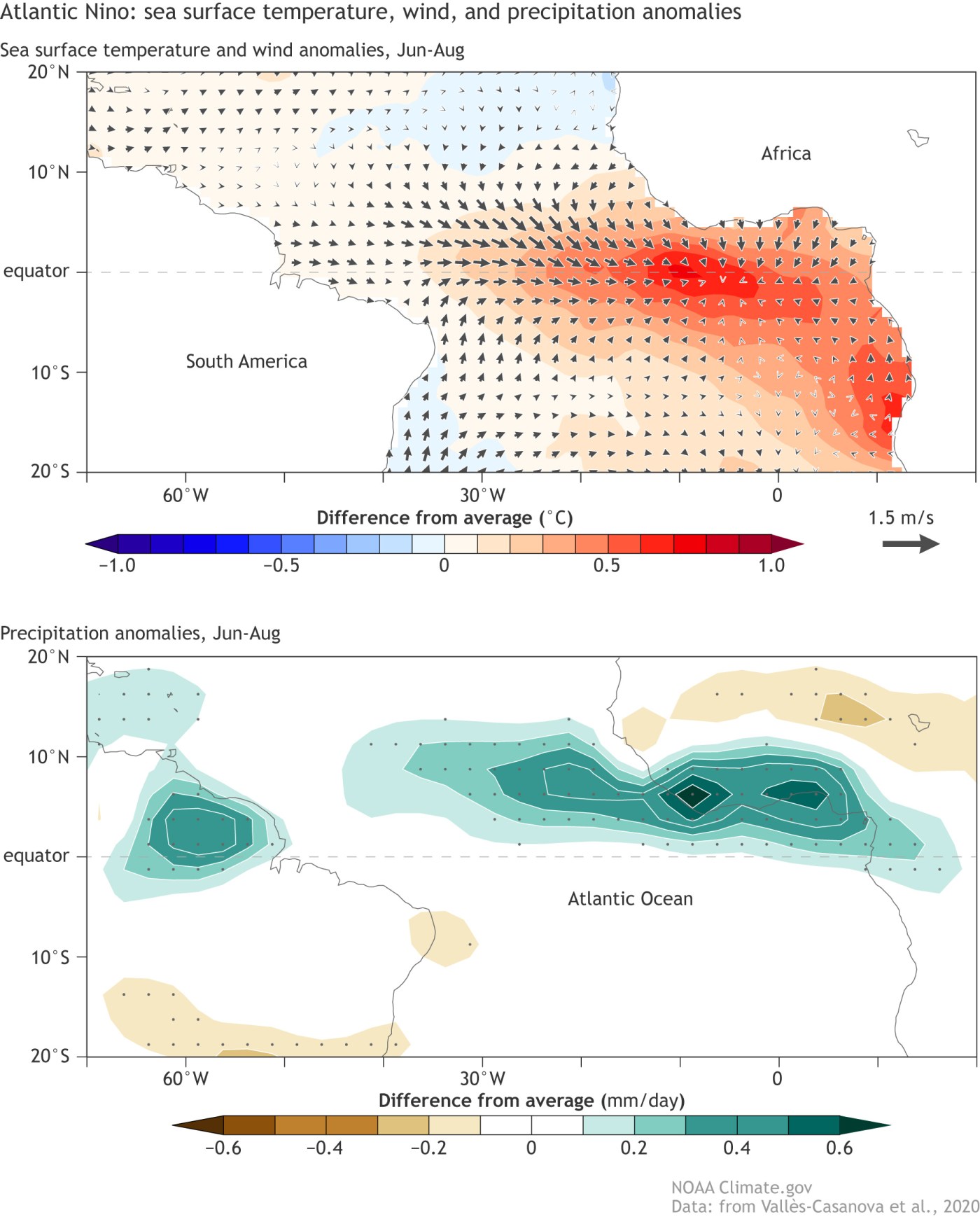

Most of us have heard of El Niño, the powerful climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean that can disrupt weather worldwide. But the Pacific isn’t the only ocean with a recurring climatic pulse. The Atlantic has its own quieter cousin, a phenomenon known as the “Atlantic Niño,” a climatic pulse that can either deliver life-giving rains to the African Sahel and the Amazon basin or withhold them.

For decades, scientists have observed that this Atlantic heartbeat has been getting weaker, its influence fading since the 1970s. The reasons for this decline have been a puzzle, but a new study points to a surprising and distant culprit: a massive ocean current system far to the north. This research reveals an unexpected link between the health of the Atlantic’s great “conveyor belt” circulation and the pulse of its tropical weather-maker. What happens when this massive current slows down, and how does a change in the subpolar North Atlantic send a message that silences a climate pattern thousands of miles away at the equator?

The Atlantic’s Giant “Conveyor Belt” Controls a Tropical Weather-Maker

New research reveals a direct and powerful connection between two of the Atlantic Ocean’s most significant features: the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and the Atlantic Niño.

In simple terms, the AMOC is the major circulation system in the Atlantic Ocean—a vast “conveyor belt” moving heat around the globe. The Atlantic Niño, on the other hand, is the primary mode of climate variability in the tropical Atlantic, an oscillating pattern of sea surface temperatures driven by interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere.

The core finding of the study is that a weakening AMOC leads directly to a weaker, or “suppressed,” Atlantic Niño. This is a critical insight because a growing body of evidence from proxy data and observations suggests the AMOC has already been weakening since the mid-20th century. This timeline is consistent with the observed reduction in Atlantic Niño activity that has been documented since the 1970s, suggesting the two phenomena are linked in the real world, not just in models.

The Slowdown Sends a Two-Part Message—One by Air, One by Sea

When the AMOC slows down, it doesn’t just affect the North Atlantic. It transmits a signal to the equator through two distinct pathways—one through the atmosphere and one through the ocean—that combine to disrupt the Atlantic Niño.

- The Atmospheric Path: A weaker AMOC is less effective at transporting heat northward. This temperature shift intensifies the North Atlantic’s subtropical high-pressure system. This, in turn, weakens the powerful easterly trade winds that blow along the equator, altering a key ingredient needed to kickstart an Atlantic Niño event.

- The Oceanic Path: As ice sheets melt, an increase in freshwater input into the subpolar North Atlantic triggers oceanic “downwelling Kelvin waves.” These waves are pulses of energy that travel southward along the western boundary of the ocean. When they reach the equator, they push the warm surface layer of water deeper, a process known as deepening the thermocline (the natural boundary layer separating warm surface water from cold, deep ocean water).

Together, both the atmospheric and oceanic pathways work to separate the warm surface water from the cooler, deeper water. This creates a “decoupling” that disrupts the delicate feedback loops between the sea and air that power the Atlantic Niño, effectively silencing its rhythm.

Our Climate Forecasts May Be Missing a Key Piece of the Puzzle

A crucial finding from the study highlights how current climate models may be underestimating future changes because many of them are missing a key process: meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet.

Researchers compared two sets of simulations: standard high-emissions climate models and identical models that also included freshwater from Greenland’s melting ice sheet. This “upwelling feedback” is a crucial part of the Atlantic Niño’s engine: it measures how effectively changes in the deep, cold thermocline can influence the temperature at the ocean’s surface. The difference between the models was stark.

By the year 2100, the models that included meltwater projected a 60 ± 6% reduction in the critical upwelling feedback that helps drive the Atlantic Niño. In contrast, the standard models without meltwater projected only a 30 ± 11% reduction. This suggests that ignoring the impact of melting ice sheets causes models to significantly under-predict the weakening of this climate pattern.

The absence of interactive ice sheets in CMIP6 models likely underestimates the magnitude of the AMOC weakening, thus possibly underestimating future Atlantic Niño decline.

The Ripple Effects Could Reshape Rainfall and Ecosystems

The consequences of a weaker Atlantic Niño are not just academic. As the AMOC slows and eventually collapses in the model simulations, the Atlantic Niño’s warming pattern shrinks and shifts, with the warming core moving towards the central equatorial Atlantic. This leads to tangible changes in regional weather.

The study’s models project significant shifts in rainfall patterns:

- Drier conditions are expected in south equatorial and tropical western Africa.

- Increased precipitation is projected for northeastern Brazil.

- The Atlantic Niño’s influence on rainfall in the eastern Amazon diminishes.

Beyond weather, there are potential ecological impacts. The deeper thermocline and reduced upwelling described earlier could starve the upper ocean of essential nutrients. This could have a profound negative impact on marine life and harm the productivity of tropical Atlantic fisheries that regional economies depend on.

A More Connected and Fragile System

This research paints a clear picture of a deeply interconnected climate system, where the stability of deep-ocean circulation in the North Atlantic is intimately tied to the behavior of a critical tropical climate pattern thousands of miles away. The slowdown of the AMOC, driven by global warming and melting ice, isn’t a localized event; it sends ripples across the entire Atlantic basin.

This research reveals that the planet’s climate system has hidden circuits, where a change in one remote region can quietly flip a switch thousands of miles away. The critical question is no longer just if these connections exist, but how many more we have yet to discover.

Freire-Souza, P., Pontes, G.M., Menviel, L. et al. Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation slowdown suppresses Atlantic Niño variability. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01222-6

Figure from climate.gov ENSO blog “Do you know that El Niño has a little brother?” (top) The sea surface temperature (shaded contours), 10-meter wind (vectors), and (bottom) rainfall departures from average in June – August during an average Atlantic Niño. The gray dots in the bottom panel indicate that the rainfall departures are statistically significant (5% significance level), indicating a high degree of confidence that the rainfall departures are associated with Atlantic Niño. Climate.gov figure adapted from Vallès‐Casanova et al. (2020).

Leave a comment