This blog post and the “Deep Drive” podcast on a new paper “Atmosphere-driven processes in shaping long-term climate variability in Greenland and the broader subpolar North Atlantic” by Li et al. (2025) was created by NotebookLM.

Deep Dive Podcast “The Wind-Driven Mystery of the North Atlantic Warming Hole: How Atmospheric Swings Orchestrate Ocean Heat and AMOC Uncertainty” powered by NotebookLM:

Introduction: The North Atlantic’s Cold Spot Mystery

In a world grappling with the clear and present reality of global warming, one patch of the ocean has long stood out as a stubborn anomaly. South of Greenland, a region of the Subpolar North Atlantic has shown a persistent cooling trend over recent decades, earning it the nickname the “warming hole.” For years, scientists have debated its cause, often pointing to a potential slowdown in the deep ocean currents that act as a massive heat conveyor belt.

But what if this cooling patch isn’t the simple story we thought it was? What if the primary driver isn’t the deep ocean at all, but something much faster and more dynamic happening in the atmosphere above? A new study by Zhe Li and colleagues, published in Climate Dynamics, challenges common assumptions and reveals a more complex and fascinating story. The research uses a combination of reanalysis data, climate model experiments, and historical reconstructions to untangle the forces at play. This article will break down the five most surprising takeaways from this new research.

1. The “Warming Hole” is a Recent Cooling Snap After an Intense Warming Sprint

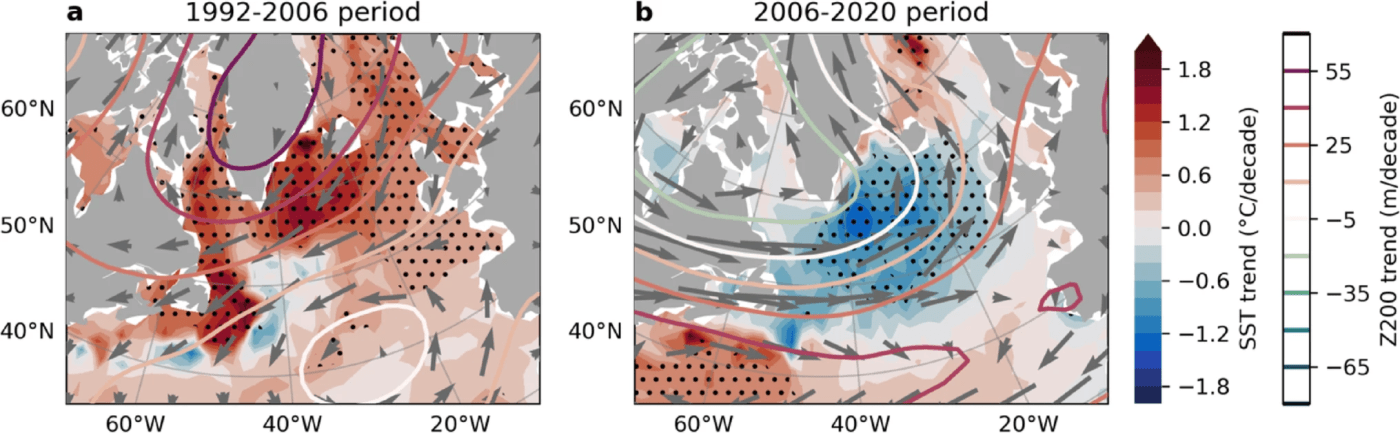

The term “warming hole” suggests a steady, continuous cooling process. However, the new research reveals this is a misconception. The cooling trend that defines the phenomenon is actually a very recent event that comes on the heels of a period of rapid warming. The data shows two distinct and dramatic epochs over the last thirty years:

- 1992 to 2006: A period of intense warming, where sea surface temperatures in the region increased at a rate of 0.74°C per decade.

- 2006 to 2020: A period of pronounced cooling, with temperatures dropping at a rate of -0.53°C per decade.

This detail is crucial because it reframes the “warming hole” from a persistent, slow-moving anomaly into a highly dynamic region subject to powerful decadal swings. The cooling we’ve observed recently isn’t a permanent state but the latest phase in a dramatic climate tug-of-war.

2. Forget the Deep Ocean for a Moment—The Atmosphere is Calling the Shots

Many prominent explanations for the warming hole focus on a slowdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a system of deep ocean currents. While the AMOC is undoubtedly a critical part of the long-term climate system, this study argues that for the recent decadal changes, the atmosphere is in the driver’s seat.

The researchers found a strong correlation between atmospheric pressure systems over Greenland and the temperature of the ocean below. High-pressure systems (anticyclones) are consistently linked with ocean warming, while low-pressure systems (cyclones) are linked with ocean cooling. The most compelling piece of evidence comes from a lead-lag analysis, which examined the timing of these events. The study found that changes in the atmosphere precede changes in the sea surface temperature by about one month, strongly suggesting that the atmosphere is causing the ocean to react, not the other way around. But this raises a critical question: how does the air exert such powerful control over the sea?

3. It’s All in the Wind: An Atmospheric Gatekeeper for Ocean Heat

So, how exactly does atmospheric pressure over Greenland change the temperature of a massive body of water? The mechanism identified by the study is all about the wind.

When a high-pressure anticyclonic system sits over the region, it generates powerful easterly winds. These winds, in turn, drive an ocean current pattern (anomalous Ekman flow), which pushes surface water at an angle to the direction of the wind, effectively pushing more warm water from lower latitudes northward into the Subpolar North Atlantic. This process is known as Poleward Ocean Heat Transport (POHT). Conversely, when a low-pressure cyclonic system dominates, it generates westerly winds that inhibit this northward flow of warm water. The study found that this wind-driven modulation of ocean heat was the key factor behind the recent decadal warming and cooling phases, playing a more significant role than the direct exchange of heat at the ocean’s surface.

The paper summarizes this core finding unequivocally:

Large-scale atmospheric circulation explains a substantial portion of the observed SST, and upper POHT variabilities in the SNA through a wind-driven process operating on both interannual and interdecadal time scales.

This intricate local dance between wind and water, however, is not a self-contained system; its choreography is being influenced by rhythms from halfway across the planet.

4. A Ripple Effect From Across the Globe: The Tropical Pacific Connection

The atmospheric patterns driving this North Atlantic drama are not just a local affair. The study confirms their connection to climate events happening halfway around the world, through a phenomenon known as an atmospheric teleconnection—think of it as a domino effect in the climate system.

Specifically, the research shows that the atmospheric circulation over the North Atlantic is linked to sea surface temperature changes in the east-central tropical Pacific Ocean (ETPO). In recent decades, an out-of-phase relationship has emerged: a warming pattern in the tropical Pacific corresponds with atmospheric conditions that lead to the cooling pattern in the Subpolar North Atlantic. This confirms a known climate link called the “Pacific-Arctic” (PARC) teleconnection, highlighting the surprising global interconnectedness that drives this seemingly regional phenomenon.

5. This is an Old Story, and Our Climate Crystal Balls Are Blurry

To understand if this atmosphere-ocean dance is a recent development or a long-standing feature, the researchers looked back in time. Using a paleo-reanalysis dataset (EKF400v2) that reconstructs atmospheric conditions over the past 150 years (from 1854 to 2003), they found something remarkable. The fundamental coupling between North Atlantic atmospheric circulation, sea surface temperature, and even the link to the tropical Pacific has been a robust and persistent feature of the climate system. This suggests that the dramatic swings we’ve seen recently are primarily the product of natural, internal climate variability that has been operating for a very long time.

This historical context has critical implications for climate science today. While the latest generation of climate models (CMIP6) can, on average, reproduce the North Atlantic cooling pattern, the study reveals a deeper and more troubling flaw: they often get the right answer for the wrong reasons. The observed cooling is primarily caused by changes in atmospheric winds that reduce the northward flow of warm ocean water. In contrast, the models tend to produce the cooling through other mechanisms, even while showing an increase in that northward ocean heat transport—the exact opposite of reality.

This is a far more significant problem than simply being inaccurate. It suggests the models may be fundamentally misrepresenting the physics driving decadal change in this region, creating a false sense of confidence in their projections. If models cannot reliably replicate these powerful natural swings, it limits their accuracy in forecasting future regional climate change, particularly the rate of Greenland’s ice sheet melt and its contribution to global sea-level rise.

Conclusion: A More Dynamic View of Our Climate

The North Atlantic’s “warming hole” is far more than a simple cold spot in a warming world. This new research paints a picture of a dynamic, atmosphere-driven process where winds act as a gatekeeper for ocean heat, responding to climate rhythms that span the globe and have deep roots in the Earth’s history. It serves as a powerful reminder that on top of the steady, human-caused warming trend, our planet has powerful natural cycles that can cause dramatic regional shifts over decades.

This revelation presents a profound challenge and a crucial new frontier for climate science. The discovery that our primary tools for predicting the future—our most advanced climate models—are missing a key piece of the puzzle in this critical region is a call for humility and intense focus. The scientific community must now move from observing these complex dynamics to correctly simulating them. Accurately projecting sea-level rise and future climate depends on our ability to build models that not only get the right answer, but get it for the right reasons.

Figure 2 from Li et al. (2025): a–b. Linear trend of annual ORAS5 SST (shading), ERA5 200 hPa geopotential height (Z200, contours), and 200 hPa horizontal winds (arrows) for the period 1992–2006 in a, and for the period 2006–2020 in b. Black stippling in all plots indicates statistically significant trends at the 95% confidence level.

Li, Z., Ding, Q., Ballinger, T.J., Topál, D., Baxter, I. & Zhang, L. Atmosphere-driven processes in shaping long-term climate variability in Greenland and the broader subpolar North Atlantic. Clim Dyn 63, 438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-025-07852-z

Leave a comment