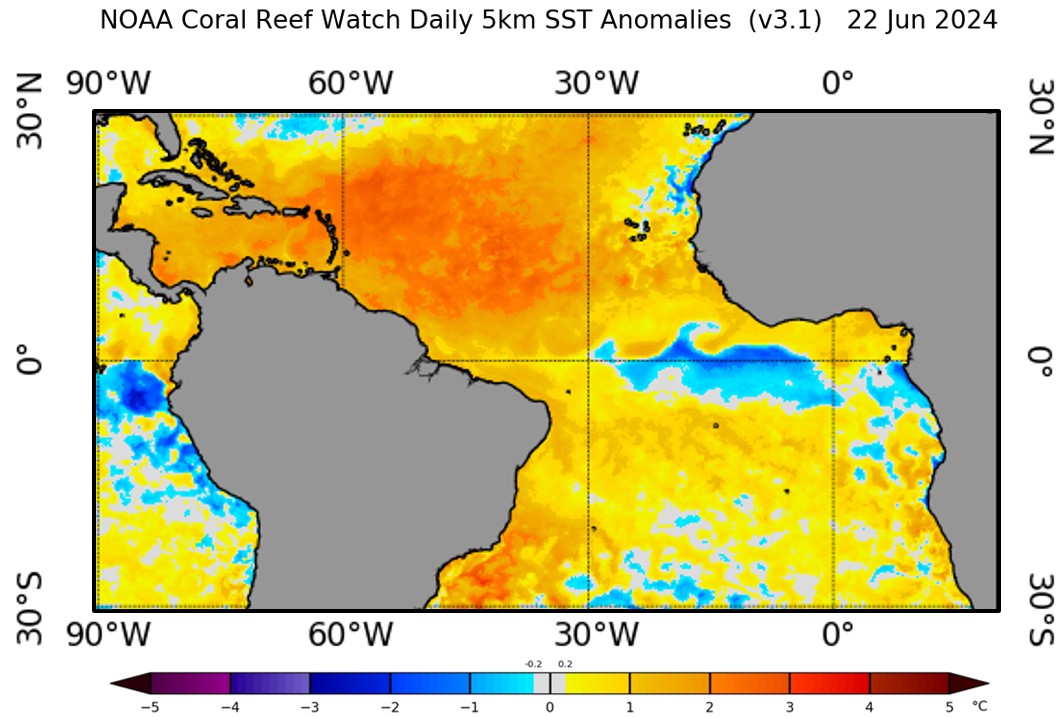

Currently (as of June 22, 2024), a phenomenon known as Atlantic Niña is brewing in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. As the Atlantic counterpart of La Niña in the Pacific, Atlantic Niña is characterized by the appearance of cold sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) in the eastern equatorial Atlantic. It is known to reduce rainfall and the frequency of extreme flooding over the West African countries bordering the Gulf of Guinea and northeastern South America (e.g., Vallès-Casanova et al., 2020). A recent study published in Nature Communications (Kim et al., 2023) showed that Atlantic Niña may also interfere with the formation of powerful hurricanes in the deep tropics, known as Cape Verde hurricanes. According to Wikipedia, “Cape Verde hurricanes are often the largest and most intense storms of the season due to having plenty of warm open ocean over which to develop before encountering land or other factors prompting weakening. A good portion of Cape Verde storms are large, and some, such as hurricanes Allen, Ivan, Dean, and Irma have set various records. Most of the longest-lived tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin are Cape Verde hurricanes.” So, how does Atlantic Niña affect Cape Verde hurricanes? Kim et al. (2023) stressed that El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM), two climate modes of variability known to modulate Atlantic hurricane activity, develop predominantly in winter or spring and are weaker during the Atlantic hurricane season (June–November), whereas the leading mode of tropical Atlantic climate variability during the Atlantic hurricane season is Atlantic Niño/Niña. This study used observations to show that Atlantic Niña weakens the Atlantic inter-tropical convergence zone rainband. This, in turn, suppresses African easterly wave activity and low-level cyclonic rotation across the deep tropical eastern North Atlantic. Such conditions decrease the likelihood of powerful hurricanes developing in the deep tropics near the Cape Verde islands, reducing the risk of major hurricanes impacting the Caribbean islands and the U.S.

The 2024 hurricane season is expected to be strongly affected by both the negative phase of ENSO (La Niña) and the positive phase of AMM (i.e., warm tropical North Atlantic). Both La Niña and warm tropical North Atlantic conditions tend to promote active Atlantic hurricane season (e.g., West et al., 2022). So, depending on the outcome of the threeway tug-of-war between La Niña, (+) AMM, and Atlantic Niña during the next several months, the developing Atlantic Niña condition may put a damper on the number of major hurricanes affecting the U.S. and the Caribbean islands in this Atlantic hurricane season.

Image Credit: https://www.ospo.noaa.gov/Products/ocean/sst/anomaly/

Kim, D., Lee, SK., Lopez, H. Foltz, GR., Wen, C., West, R. & Dunion, J. (2023). Increase in Cape Verde hurricanes during Atlantic Niño. Nature Communications, 14, 3704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39467-5

Vallès‐Casanova, I., Lee, S.‐K., Foltz, G. R., & Pelegrí, J. L. (2020). On the spatiotemporal diversity of Atlantic Niño and associated rainfall variability over West Africa and South America. Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2020GL087108. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087108

West, R., Lopez, H., Lee, S.-K., Mercer, A., Kim, D., Foltz, G., & Balaguru, K. (2022). Seasonality of interbasin SST contributions to Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2021GL096712. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL096712

I don’t favor the term ‘Atlantic Niña’ because it tends to confuse things. I favor terms like warm or cool North Atlantic. My understanding is that the North Atlantic has been generally warm and that, combined with a La Niña in the Pacific, the development of tropical waves in the Atlantic will be favored due to reduced wind shear (cool Pacific + warm North Atlantic). I think the equatorial Atlantic SST will have less to do with storm development. IMHO.

>

Hi David,

Atlantic Niño/Niña describes warm/cold SSTAs in the eastern equatorial Atlantic, much like El Niño/La Niña in the Pacific. The idea of Atlantic Niño/Niña affecting the development of Cape Verde Hurricanes is relatively a new concept proposed by Kim et al. (2023). But, I agree with you that this year’s hurricane season will be largely determined by the developing La Niña and warm tropical North Atlantic conditions.

Best,

Sang-Ki

Climate.gov: Atlantic Niña on the verge of developing. Here’s why we should pay attention

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/atlantic-nina-verge-developing-heres-why-we-should-pay-attention

I am wondering what Atlantic niña’s impact would be on the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation).

I’m not a professional oceanographer so this might just be another silly layperson’s question but I’m curious.

Hi Rangfar,

That’s a great question. The AMOC transport mass, heat and other ocean tracers from the South to North Atlantic. So, the equatorial Atlantic is an important gateway of the upper limb of the AMOC (i.e., the northward transport branch of the AMOC). So, if the AMOC suddenly stops for some reasons, the equatorial upwelling has to decrease, thus producing a permanent Atlantic Nino condition.

From here, it becomes more technical. How it actually works is that the North Atlantic will be much colder compared to the South Atlantic since the heat is not transported to the North. As a result, the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) rain band has to migrate toward the equator from its current position at around 10N. ITCZ is the region of minimum trade wind, as known as Doldrum. So, the easterly trade wind will be weakened along the equator. Thus, the zonal tilting of the equatorial thermocline will be relaxed, deepening the thermocline in the east and thus producing a permanent Atlantic Nino condition (i.e., reduced equatorial upwelling).

Hope this answered your question.

Sang-Ki

Climate.gov: Four things to know about a possible Atlantic Niña

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/four-things-know-about-possible-atlantic-nina