This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Rainfall sustains multiyear La Niña” by Tian et al. (2026).

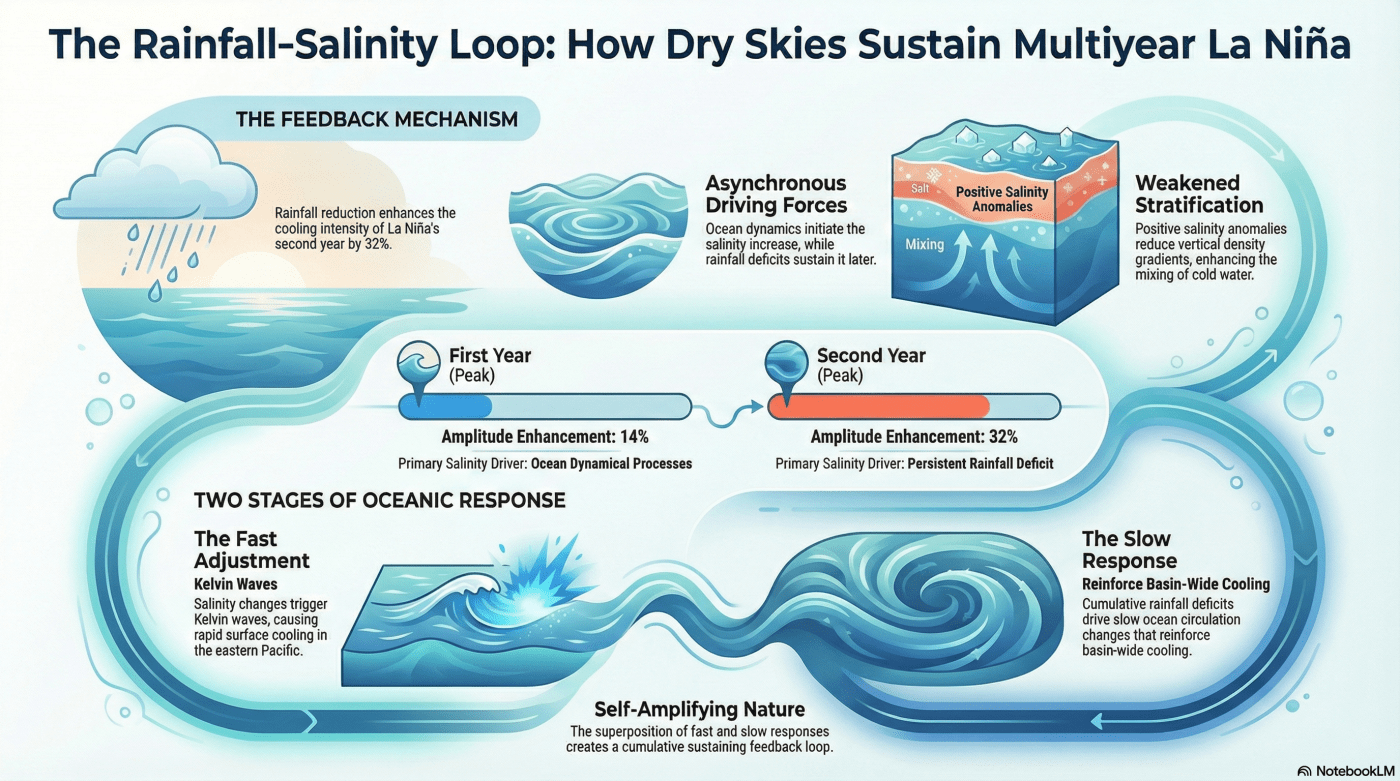

This research investigates how rainfall-induced salinity changes act as a critical feedback loop to sustain multiyear La Niña events. While early stages of these cooling events are driven by ocean dynamics like advection, the study reveals that persistent rainfall deficits in the western-central Pacific lead to higher surface salinity. These positive salinity anomalies weaken upper-ocean stratification, allowing colder subsurface water to mix upward and reinforce surface cooling. Quantitative models show that this rainfall–salinity feedback amplifies La Niña’s intensity by 14% in the first year and 32% in the second. By integrating rapid equatorial waves and slower circulation adjustments, the authors demonstrate that cumulative rainfall anomalies are essential for preventing the tropical Pacific from returning to a neutral state. These findings offer a new mechanical framework for improving climate predictability regarding prolonged environmental shifts.

From 2020 to 2022, the tropical Pacific did something that defied standard thermodynamic expectations. Instead of recovering toward a neutral state after a year of cooling, the ocean locked itself into a rare “triple-dip” La Niña, chilling the globe for three consecutive years. Traditionally, meteorologists have viewed these events as a simple tug-of-war between surface winds and water temperature. But this conventional framework fails to explain the system’s strange persistence—why it refuses to thaw even when the initial atmospheric nudge has faded.

New research by Tian et al. (2026) has uncovered a hidden protagonist in this climate drama: the ocean’s salt. It appears that the Pacific possesses a previously overlooked “salty memory” that allows it to self-fuel its own cold state. By altering the very density of the upper ocean, a lack of rainfall creates a feedback loop that doesn’t just respond to La Niña, but actively sustains it.

1. The Asynchronous Hand-off: From Waves to Weather

The core of this discovery lies in Mixed-Layer Salinity (MLS). In the western-central Pacific, the ocean is usually capped by a layer of fresh, buoyant water sustained by heavy tropical rains. During a La Niña, this balance shifts, but the transition is more nuanced than scientists previously realized.

The Tian et al. study reveals an “asynchronous” response. In the early stages of a multiyear event—specifically the spring and summer of the first year—the initial salinification of the surface isn’t caused by a lack of rain. Instead, it is driven by oceanic dynamical processes: anomalous westward currents advect saltier water into the region, while increased vertical mixing pulls salt up from below.

However, as the event matures into the winter of the first year and through the second, the driver changes. The persistent rainfall deficit takes over as the primary engine of salinification. This saltier water increases the surface density, which fundamentally alters the ocean’s “buoyancy frequency” (N2). As the vertical density gradient weakens, the stratification—the ocean’s internal layering—begins to crumble. This allows cold subsurface water to “mix up” more easily, keeping the surface chilled long after the initial winds have died down.

“These findings identify rainfall–salinity feedbacks as a key mechanism sustaining multiyear La Niña events.”

2. The 32% Factor: A Compounding Physical Memory

In the world of climate modeling, the second year of a La Niña was often viewed as a lingering shadow of the first. The data from Tian et al. suggests otherwise; it is a reinforced, secondary strike. By isolating the impact of rainfall-induced salinity, the researchers quantified a massive compounding effect:

- Year One: The reduction in rainfall enhances the La Niña cooling amplitude by 14%.

- Year Two: The effect more than doubles, boosting the amplitude by 32%.

This is a game-changer for prediction. It suggests that the rainfall deficit creates a physical “memory” in the water column. The second year of a “triple-dip” isn’t just a failure to recover; it is the result of the previous year’s salt anomalies lowering the threshold for further cooling.

3. The Cold Signal’s Eastward Shortcut: Fast Waves and Slow Currents

The ocean’s response to these salinity changes operates across a “tale of two speeds,” involving complex geophysical adjustments that span the entire basin.

The Fast Response: The High-Order Baroclinic Adjustment Within just two to three months of the salinity increase in the western-central Pacific, the eastern Pacific begins to cool. This rapid response is triggered by a “high-order baroclinic adjustment.” The increased surface density excites equatorial Kelvin waves that carry a unique “vertical sandwich” of temperatures eastward: a structure of alternating cold-warm-cold-warm layers. Crucially, a sharp cold signal hitches a ride on the core of the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC), allowing the western drought to “telegraph” its cooling effect to the South American coast with startling speed.

The Slow Response: Sea Surface Height and Circulation While the waves provide the shock, a slower set of processes provides the staying power. Persistent salinity anomalies alter the sea surface height (SSH) gradients across the Pacific. This reduced gradient strengthens the westward surface currents and intensifies upwelling in the east. This slow circulation shift, combined with the sustained weakening of the buoyancy frequency (N2), ensures that the basin-wide chill remains locked in for years.

“The superposition of rapid and slow oceanic responses creates cumulative positive feedback from rainfall on the second-year La Niña.”

4. Why This Matters for a Warming World

Understanding the “salty secret” of the Pacific is not merely an academic victory; it is a necessity for a 21st-century survival strategy. We are already seeing the “zonal migration of the western Pacific warm pool”—the engine of global weather—shifting in response to these multiyear cycles.

As the global hydrological cycle accelerates, the stakes for ENSO prediction have never been higher. Multiyear La Niña events are becoming more frequent in both historical observations and climate models. These prolonged events don’t just mean a few extra cool months; they cause cumulative shifts in rainfall that lead to devastating multi-year droughts and catastrophic flooding on opposite sides of the globe.

Conclusion: The Future of the Pacific

The research from Tian et al. forces us to recalibrate our understanding of the Pacific’s “memory.” We can no longer treat rainfall as a mere passenger of climate cycles; it is a primary driver that uses salinity to rewrite the ocean’s physical structure.

As we move into a future where the atmosphere holds more moisture, the central question for climate science becomes: will a warmer world lead to even more extreme rainfall deficits in the Pacific, effectively supercharging these “salty feedbacks” and making “endless” La Niñas the new global norm? If so, the salt in the water may soon dictate the life and death of harvests for billions of people.

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Tian, F., Zhang, RH., Liu, C. et al. Rainfall sustains multiyear La Niña. Nat Commun 17, 1744 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68451-y

Leave a comment