This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Deep convection in the Irminger Sea forced by the Greenland tip jet.” by Pickart et al. (2003).

This research by Pickart et al. (2003) identified the Greenland tip jet as the primary driver of deep ocean convection in the southwest Irminger Sea. While scientists previously believed mid-depth waters in the North Atlantic originated solely from the Labrador Sea, this study demonstrated that intense wind bursts near Cape Farewell trigger significant localized mixing. These atmospheric events are most frequent during years with a high North Atlantic Oscillation index, leading to substantial heat loss and shifts in oceanic circulation. By combining meteorological data with numerical modeling, the authors showed that the Irminger Sea is a vital second source of deep water. These findings challenged traditional views of the meridional overturning circulation and highlight how small-scale weather patterns impact global climate systems.

Introduction: The Ocean’s Deep Breath

The Earth’s oceans are not just vast bodies of water; they are the planet’s circulatory system and its primary climate regulator. A critical part of this system is deep convection, a process where frigid, dense surface water sinks into the abyss. This sinking acts as a planetary-scale heat pump, pulling tropical warmth toward the poles and transporting life-giving oxygen to the deep sea. For decades, the scientific consensus was that this vital “breathing” in the North Atlantic occurred almost exclusively in one place: the Labrador Sea.

This was a foundational belief in modern oceanography. Yet, what if the textbooks were wrong? In a stunning turn of events, a nearly 100-year-old, long-dismissed theory has been resurrected. Scientists, armed with new high-resolution technology, have uncovered a powerful and previously hidden atmospheric phenomenon off the coast of Greenland. The discovery of this mechanism revealed a second major source of the Atlantic’s deep water, solving a long-standing puzzle and proving that our planet’s climate engine is more complex and dynamic than we ever imagined.

1. The Textbooks Were Wrong: The Labrador Sea Isn’t the Only Source

For much of the last century, the globally accepted view was that a critical water mass that fills the mid-depths of the ocean, known as “Labrador Sea Water,” was formed entirely in the Labrador Sea through intense wintertime cooling. This idea was so entrenched that the water mass itself was named for what was believed to be its sole place of origin.

Remarkably, nearly a century ago, some scientists hypothesized that the Irminger Sea, located east of Greenland, was actually the main source. They argued that the Labrador Sea’s surface water was too fresh to become dense enough to sink to the required depths. Over decades of scientific debate, however, this alternate theory eventually “fell out of favour,” and the Labrador Sea was crowned the exclusive driver of this critical process.

The established dogma being challenged was clear, powerful, and woven into the fabric of oceanography:

Today, it is commonly accepted that the body of weakly stratified water found at mid-depth (500–1,500 m) in the North Atlantic stems entirely from the Labrador Sea—hence the term ‘Labrador Sea Water’.

But now, compelling new evidence has reawakened this old idea. The finding sent ripples through the oceanographic community, suggesting that the circulation of the North Atlantic is far more intricate than previously thought and forcing a revision of long-held theories about how our oceans work.

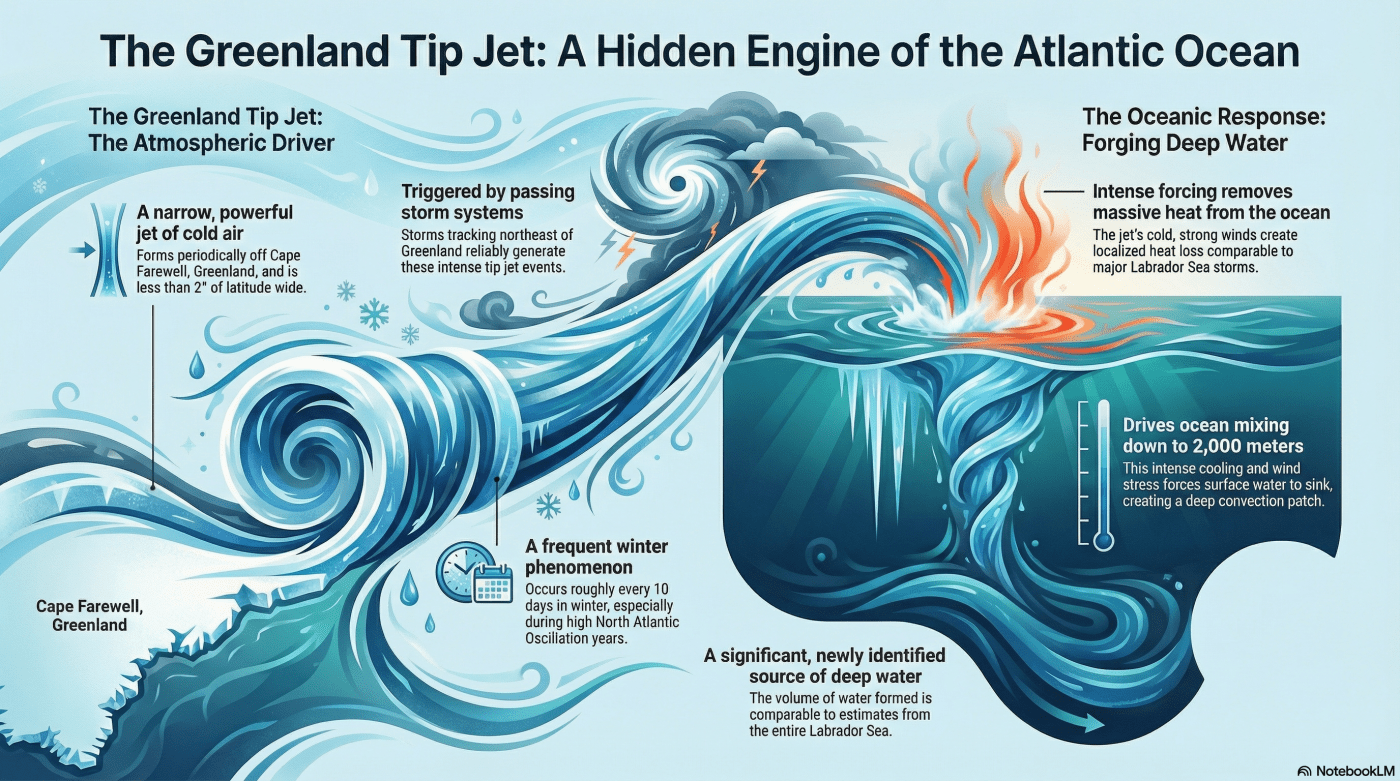

2. A Hidden Driver: The Greenland Tip Jet

The culprit behind the mysterious convection in the Irminger Sea is a phenomenon called the “Greenland tip jet.” Its formation is a testament to the power of topography: when high-level northwesterly winds slam into Greenland’s massive ice sheet, they are forced downward on the eastern side. This descending air accelerates dramatically, pulling frigid polar air over the sea in a narrow, ferocious, low-level jet off Greenland’s southern tip, Cape Farewell.

For decades, this powerful engine remained hidden in plain sight. Its small size—spanning less than two degrees of latitude—made it a ghost in our global weather models. Coarse, low-resolution models like the NCEP reanalysis, which averaged data over large areas, completely missed its impact. In these models, the tip jet was “nearly indiscernible,” its intense but short-lived fury smeared into the background noise of regional weather. What the models revealed was stunning: while NCEP showed a heat loss of only 225 W m⁻², the high-resolution COAMPS model showed the true value was more than double, at 475 W m⁻². It wasn’t until scientists could finally deploy high-resolution regional models and detailed satellite data that the tip jet’s signature was seen to dominate the entire month’s average, finally revealing its true power.

The force of this jet is immense. It blasts cold air over the sea at a rate comparable to the most intense storms in the Labrador Sea. At the same time, its narrow, focused power creates a strong, localized wind stress curl that violently churns the ocean surface, playing a crucial role in preparing it for its deep plunge.

3. A Surprisingly Common Phenomenon

This discovery was not of a rare, once-a-century storm, but of a regular and predictable feature of the North Atlantic winter. Analysis of decades of data from meteorological stations shows that a tip-jet event occurs with remarkable regularity, happening “roughly every 10 days” during the winter months from December to March, with each event lasting for about three days.

What was truly remarkable was the discovery of its trigger. These events are not random; they are astonishingly predictable. The connection was so direct it was like a switch. The data showed that every single time a low-pressure storm system passed through a specific “trigger box” of ocean between Greenland and Iceland, a powerful tip jet was born. The study found that this happened “without exception.”

The frequency of these jets is directly linked to a larger climate pattern, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). During a high NAO index, the storm track shifts northeast, steering more storms into the trigger box. This leads to more tip-jet events, creating more favorable conditions for deep ocean convection in the Irminger Sea.

4. A Second Engine for Ocean Circulation

The ocean’s response to these jets is nothing short of dramatic. The combination of intense cooling and ferocious wind makes the surface water of the Irminger Sea incredibly dense, causing it to plunge downwards in what can only be described as a massive open-ocean chimney. This column of sinking water creates a patch of deep mixing—or convection—that can extend to depths of 2,000 meters.

Crucially, the wind does more than just cool the water. The strong wind stress curl actively helps precondition the ocean by pulling away the warm, buoyant surface layer through a process called Ekman suction. This exposes the cooler water beneath, reducing the amount of heat that needs to be removed before sinking can begin. This dual-action mechanism is a key difference from other convection sites; models show that without the wind’s preconditioning effect, the volume of deep water formed would be reduced by approximately 35%.

The scale of this process is what solidifies its importance as a paradigm shift. The volume of new, dense water formed in the Irminger Sea is significant and directly comparable to that of the Labrador Sea. One model estimated that a single winter’s worth of tip-jet events created 4.5 x 10¹³ cubic meters of new deep water—a volume that could fill the Great Lakes twice over. For comparison, direct measurements from the Labrador Sea during the winter of 1996–97 showed the formation of 4.0 x 10¹³ cubic meters.

This finding firmly establishes that the Irminger Sea is not a minor contributor but “a significant source” of deep water. It acts as a second major engine, working in concert with the Labrador Sea to drive the vital mid-depth circulation of the entire North Atlantic.

Conclusion: Small-Scale Events, Climate-Sized Consequences

The discovery of the Greenland tip jet and its profound impact on the Irminger Sea fundamentally changes our understanding of ocean circulation. It reveals that a series of fleeting, localized atmospheric events, once invisible to our best models, can collectively drive a massive, climatically critical ocean process. What was once dismissed as an incorrect, century-old theory is now recognized as a key piece of the global climate puzzle.

This research underscores the hidden complexities of our planet’s systems and the surprising power of small-scale phenomena to shape global patterns. It is a powerful reminder that there are still fundamental discoveries to be made about how our world works, often in the places we least expect.

“Our results also provide a striking example of the coupling that can occur between high-frequency, small-scale events in the atmosphere, and low-frequency, climatically import-ant processes in the ocean.”

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Pickart, R., Spall, M., Ribergaard, M. et al. (2003). Deep convection in the Irminger Sea forced by the Greenland tip jet. Nature 424, 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01729

Leave a comment