This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Decadal changes in Atlantic overturning due to the excessive 1990s Labrador Sea convection” by Böning et al. (2023).

Deep beneath the surface of the Atlantic, a colossal current system is constantly at work. Known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), this “great ocean conveyor belt” acts as a planetary-scale engine, transporting immense quantities of heat northward. This process is crucial for regulating the climate of the Northern Hemisphere, helping to keep regions like Western Europe milder than they would otherwise be. For decades, scientists have been working to understand the intricate mechanisms that cause this vital system to speed up or slow down over time.

A central part of this puzzle has focused on a specific region: the Labrador Sea, nestled between Canada and Greenland. The prevailing theory was that the intensity of deep winter convection—a process where cold winds cool the surface water until it becomes dense enough to sink—in this sea was a key driver of the AMOC’s decadal changes. This idea seemed logical, but it has been challenged by observational data that didn’t quite fit the theory.

Now, new research based on an incredibly detailed, high-resolution ocean model has provided a clearer picture. The simulations resolve a long-standing debate and reveal a surprising and more complex story about what truly drives the Atlantic’s great conveyor belt. The engine, it turns out, is not where we’ve primarily been looking, and its power is activated in a much more dramatic fashion than previously understood.

1. The Real Powerhouse Isn’t the Labrador Sea

For a long time, many modeling studies pointed to the Labrador Sea as the main arena for changes in the AMOC. The logic was that intense winter cooling in this area would create vast amounts of dense water, which would then sink and power the southward flow of the deep ocean, effectively driving the entire conveyor.

However, recent on-the-water observations and the new model simulations challenge this long-held idea. The study confirms that the vast majority of the “downwelling”—the critical process where warm surface water transforms into deep, cold water—actually takes place further east. The real powerhouses are the Irminger and Iceland basins in the northeastern Atlantic, broadly between Greenland, Iceland, and Europe. This finding represents a significant shift in understanding for oceanographers, moving the focal point of the AMOC’s engine across the ocean.

“The bulk of the downwelling limb of the AMOC occurs in the Irminger and Iceland basins, with a very weak additional contribution from the Labrador Sea”

2. A Historic Cold Snap Remotely Supercharged the AMOC

While the Labrador Sea isn’t the primary engine for year-to-year changes, the study reveals it can have a dramatic, indirect influence under specific circumstances. The model highlights an “outstanding episode” during the exceptionally cold winters in the first half of the 1990s. This period of intense cooling created a huge volume of uniquely and exceptionally dense Labrador Sea Water (LSW).

The model’s surprising discovery was what happened next. This massive plume of dense water didn’t just strengthen the AMOC locally. Instead, it spread rapidly northeastward along a “fast path” directly into the Irminger Sea.

The consequence of this underwater invasion was profound. As this exceptionally dense water mixed into the main deep boundary current flowing south along Greenland’s coast, it was entrained into the primary downwelling engine, increasing the density of the water sinking into the abyss. This remote supercharging of the northeastern Atlantic’s engine strengthened the entire AMOC by a massive 20%.

…the exceptionally cold winters in the Labrador Sea during the first half of the 1990s induced a positive AMOC anomaly of more than 20%, mainly by augmenting the downwelling in the northeastern North Atlantic.

This remote-control mechanism does more than just explain a past event; it offers a potential solution to a major scientific puzzle. For years, oceanographers have been trying to understand observations from the subtropical Atlantic (at 26.5°N) that show a declining trend in the deepest part of the AMOC. This was baffling because the primary sources for these abyssal waters—the overflows from the Nordic Seas—appeared stable. The new model provides the missing link: it shows how an extreme event in the Labrador Sea can modulate the density of the deep boundary current far downstream, providing a clear causal connection between subpolar events and changes observed in the abyss thousands of kilometers to the south.

3. The AMOC Responds to Shocks, Not Whispers

The model simulations showed that the normal, year-to-year variations in convection within the Labrador Sea had a “negligible impact” on the overall strength of the AMOC. The system seems largely insensitive to these minor annual fluctuations.

This stands in stark contrast to the extreme event of the 1990s. A unique characteristic of that period was the production of a large volume of exceptionally dense Labrador Sea Water—a density and volume that have not been repeated since 1995 in the simulation. This finding suggests that the AMOC is a resilient system, capable of absorbing small, routine changes from the Labrador Sea. However, it is also highly sensitive to large, anomalous “shock” events powerful enough to create a water mass of a specific, exceptional density that can be sent across basins to influence the primary downwelling regions in the northeast.

A More Complex and Connected Ocean

This research provides a new and more nuanced perspective on one of the planet’s most important climate systems. The Labrador Sea’s influence on the AMOC is not a simple, direct link where more local sinking equals a stronger current. Instead, its role is complex and indirect, activated only by extreme cooling events that have their major impact far from the source by feeding the true engine of the system in the northeastern Atlantic.

This new understanding, made possible by incredibly high-resolution models, resolves a long-standing puzzle. It begs the question: What other secrets of our planet’s climate system will be revealed as our ability to simulate the Earth in fine detail continues to improve?

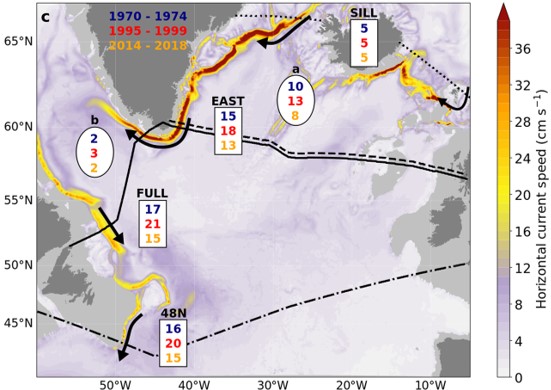

Fig. 4c from Böning et al. (2023): Map summarising the evolution of the lower limb of the AMOC for three different 5-year periods of CTRL: section transports (values in rectangles; in Sv) and diapycnal downwelling from the upper to the lower limb (values in ovals; in Sv) implied by the transport divergence between EAST and SILL (oval ‘a’), and FULL and EAST (oval ‘b’). The horizontal current speed averaged between the potential density surface 27.55 kg m−3 and the bottom (colour bar; in cm s−1) illustrates the concentration of the lower limb transport along the continental slopes of Greenland and North America. The transport evolves from two main sources, the outflow from the Nordic Seas and its enhancement by downwelling in the northeastern basins between SILL and EAST. After minor augmentation during its passage through the Labrador Sea, it reaches its maximum strength near 52°N. The increase of ~4 Sv at FULL and 48N between the 1970s and 1990s originated mainly from enhanced downwelling between SILL and EAST, with a contribution of ~1 Sv from enhanced downwelling in the Labrador Sea.

Böning, C.W., Wagner, P., Handmann, P. et al. Decadal changes in Atlantic overturning due to the excessive 1990s Labrador Sea convection. Nat Commun 14, 4635 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40323-9

A summary of the same study by me without the AI help can be found here: https://ocean2climate.org/2023/08/03/how-did-excessive-labrador-sea-convection-in-the-1990s-increase-the-amoc/