This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Impacts of a Reduced AMOC on the South America Mean Climate and Extremes” by Meccia & Blázquez (2025).

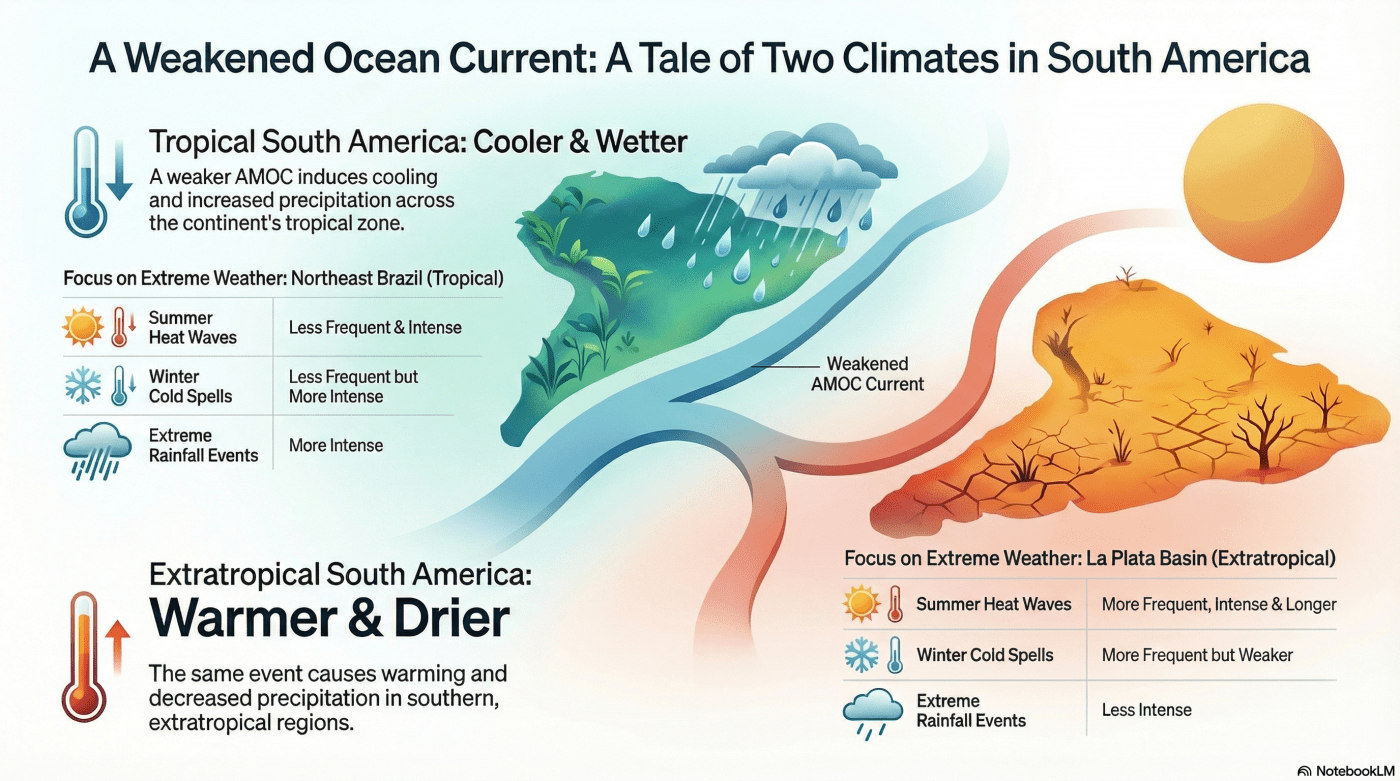

Summary: This study investigates how a weakening Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) influences the climate and weather extremes of South America. Utilizing the EC-Earth3 climate model, the study demonstrates that a slowdown in these ocean currents triggers a distinct climatic dipole, characterized by cooling and wetting in the tropics alongside warming and drying in the extratropics. These shifts are driven by a southward migration of the ITCZ and a simultaneous reduction in midlatitude storm track activity. The study highlights regional variations, noting that while the La Plata Basin may experience more intense summer heatwaves, northeast Brazil sees an intensification of extreme rainfall. Ultimately, the study concludes that an AMOC reduction can either amplify or counteract the effects of global warming, emphasizing the necessity of accurate ocean modeling for future climate predictions.

1.0 Introduction: The Planet’s Unpredictable Future

When we think about climate change, the story that usually comes to mind is a straightforward one: greenhouse gases trap heat, and the entire planet gets warmer. While this is true on a global scale, the reality is far more complex, filled with regional surprises and counter-intuitive effects. As the Earth’s climate systems are pushed into new territory, they are beginning to behave in ways we are only just starting to understand.

A new scientific study reveals one of these surprising twists, focusing on a critical circulation system in the Atlantic Ocean. This system, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), is a massive ocean current that transports heat around the globe. Projections show it is weakening due to climate change, and the consequences are not as simple as uniform warming. Instead, its slowdown is creating a bizarre “climate dipole” in South America, splitting the continent into two zones with starkly opposite futures.

2.0 Takeaway 1: South America’s Climate Is Splitting in Two

A Continental Divide: Cooling in the North, Warming in the South.

The most startling finding from the research is that a weakening AMOC creates a dramatic split in South America’s climate. The model shows that a slowdown induces cooling and increased rainfall in the tropical northern parts of the continent. At the same time, it causes warming and drier conditions in the extratropical southern regions (the areas outside of the tropics, including much of Argentina, Uruguay, and Southern Brazil).

This continental divide happens for two primary reasons. First, as the AMOC weakens, its ability to transport ocean heat northward across the equator is reduced. This leads to relative cooling in the North Atlantic that extends into tropical South America. Second, this change in ocean temperature forces major atmospheric systems to reorganize. The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)—a vital rain-bringing belt that circles the globe near the equator—is pushed southward, delivering more moisture to the tropics. Simultaneously, this atmospheric reshuffling weakens the mid-latitude storm tracks that typically bring moisture to regions like the La Plata Basin, contributing to the drier conditions there.

3.0 Takeaway 2: Extreme Weather Is Being Flipped on Its Head

Extreme Weather Gets Rewired.

These large-scale shifts in temperature and rainfall have dramatic and opposing consequences for extreme weather events across the continent. To understand these impacts, the study focused on two key regions that serve as case studies for these contrasting futures: the vast La Plata Basin (LPB), a region critical for hydroelectric power and agriculture, and Northeast Brazil (NEB), an area often grappling with severe drought.

3.1 A Tale of Two Extremes: Heat Waves and Cold Spells

Heat Waves and Cold Spells: A Story of Opposites.

This continental split—warming and drying in the south, cooling and wetting in the north—directly rewires the nature of extreme weather.

In the La Plata Basin (LPB), a region that includes parts of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, a weakened AMOC leads to a future with more punishing heat.

- Summer heat waves are projected to become more frequent, more intense, and longer-lasting.

- Winter cold spells, paradoxically, become more frequent but less intense and shorter.

In stark contrast, Northeast Brazil (NEB) experiences a more complex set of changes.

- The study’s high-level summaries point to an increase in the frequency and intensity of heatwaves. However, the detailed model results for the most severe AMOC slowdown scenario show the opposite: heat waves becoming less frequent and less intense, highlighting the complexities of modeling these large-scale shifts.

- Winter cold spells are projected to become less frequent but more intense, with uncertain effects on how long they last.

3.2 A Drastic Shift in Rainfall

Too Much Rain, or Not Enough.

The changes in extreme rainfall are just as polarized. The study analyzed the intensity of extreme precipitation events (EPEs) in the two regions and found a clear dividing line.

In the La Plata Basin, which is already prone to significant rainfall, extreme precipitation events are projected to weaken and become less intense.

Meanwhile, in Northeast Brazil, a region often grappling with drought, extreme precipitation events are projected to intensify.

4.0 Takeaway 3: A Complicated Counterweight to Global Warming

Amplifying and Offsetting Global Warming at the Same Time.

Perhaps the most crucial takeaway is that the effects of a weakening AMOC do not happen in a vacuum. They will be laid on top of the broader background trend of global warming, creating a complex and sometimes contradictory picture.

In some cases, the AMOC’s effects will amplify the impacts of global warming. For example, in the La Plata Basin, where climate change is already projected to increase heat waves, the AMOC slowdown will make them even more frequent and intense. In other cases, the AMOC’s effects may counteract or offset the impacts of global warming. The projected cooling and increased rainfall in tropical regions like Northeast Brazil could partially buffer that area from the worst of the rising global temperatures.

As the study’s authors note, this complex interaction highlights a critical point:

Some climate impacts of a weakened AMOC in South America may amplify the effects of global warming, while others could counteract them.

5.0 Conclusion: Preparing for a More Complex Climate

The slowdown of the AMOC adds a significant layer of complexity to our climate future, serving as a powerful reminder that global warming is not a monolithic event. The simple narrative of a uniformly warmer world is obsolete. This research reveals a future where one nation’s flood may be directly linked to its neighbor’s heatwave, driven by the subtle slowing of an ocean current thousands of miles away.

This research underscores the urgent need to improve our climate models and deepen our understanding of these massive Earth systems. As the planet’s systems continue to shift in unpredictable ways, we are left with a critical question: how can we refine our predictions to prepare for a future that is not just warmer, but wildly different from region to region?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Meccia, V. L., & Blázquez, J. (2025). Impacts of a reduced AMOC on the South America mean climate and extremes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 130, e2025JD044103. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025JD044103