This blog post and the “Deep Dive” podcast, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Direct human health risks of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide.” by Jacobson et al. (2019), “Fossil fuel combustion is driving indoor CO2 toward levels harmful to human cognition” by Karnauskas & Schapiro (2020), and “Is CO2 an indoor pollutant? Direct effects of low-to-moderate CO2 concentrations on human decision-making performance” by Satish et al. (2012).

We’ve all been there: sitting in a crowded meeting room or a packed classroom, a wave of drowsiness washes over you. Your focus drifts, your thoughts become sluggish, and the air feels thick and stale. We typically blame this on fatigue or boredom, but what if something else is at play? What if the very carbon dioxide (CO2) we exhale with every breath is not just making the air feel stale, but is actively impairing our cognitive abilities and potentially our long-term health?

For decades, we’ve operated under one set of assumptions about indoor air quality. Now, a growing body of scientific research is challenging those long-held beliefs, revealing startling connections between the CO2 levels in our homes, offices, and schools, and our brain function. This article untangles the evidence, revealing a disturbing story in three parts: how science pinpointed CO2 as a direct neurotoxin, how our modern indoor lives create an unprecedented exposure, , and how shockingly common these toxic environments have become.

1. The Real Culprit: CO2 Isn’t Just a Red Flag for Bad Air, It’s the Problem Itself

For years, scientists and building engineers treated carbon dioxide as a harmless “proxy” for bad air. The thinking was that high CO2 levels were simply a rough indicator that ventilation was poor, allowing other, more noxious pollutants to build up. The CO2 itself was considered benign at the concentrations typically found indoors.

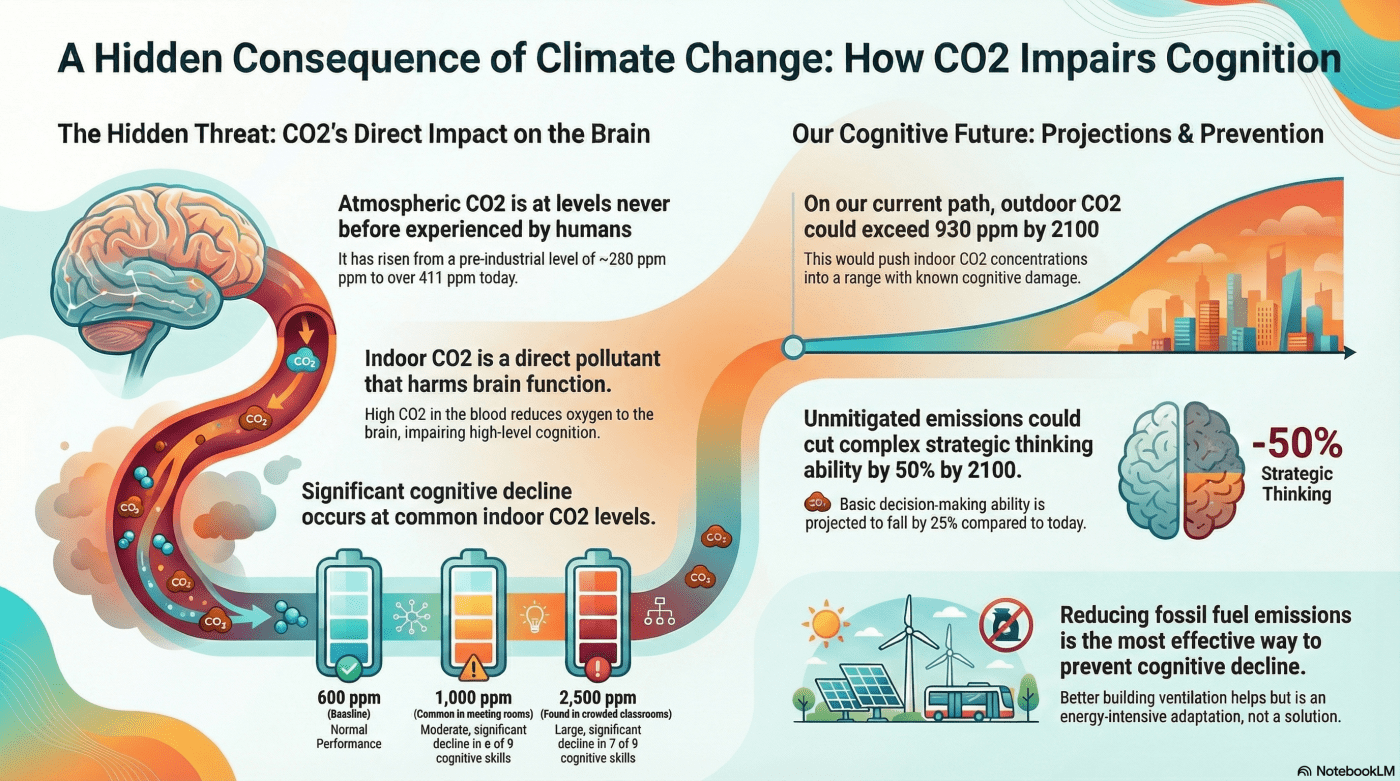

A meticulously controlled 2012 study by Usha Satish and her colleagues directly challenged this assumption. Researchers created an office-like chamber and exposed participants to various CO2 levels while keeping all other factors, including ventilation rates, constant. By injecting pure CO2, they isolated it as the sole variable. Participants were exposed to three concentrations:

- 600 ppm (a baseline representing very clean indoor air)

- 1,000 ppm (a level commonly found in well-occupied rooms)

- 2,500 ppm (a high level found in crowded, poorly ventilated spaces)

The results were striking. Compared to the 600 ppm baseline, participants’ cognitive performance changed significantly:

- At 1,000 ppm, they showed moderate but statistically significant decreases in performance on six out of nine decision-making tests.

- At 2,500 ppm, they showed large, statistically significant reductions on seven of the nine tests (impairing everything from basic initiative to complex strategy). On some metrics, their performance dropped to levels described as “marginal or dysfunctional.”

This finding is a paradigm shift. It demonstrates that CO2 is not just an innocent bystander signaling the presence of other pollutants; it is a direct indoor pollutant in its own right, with measurable effects on high-level cognitive function.

These findings provide initial evidence for considering CO2 as an indoor pollutant, not just a proxy for other pollutants that directly affect people.

2. An Unprecedented Experiment: We’re Chronically Exposed to CO2 Levels Never Before Experienced by Humans

To understand the significance of modern indoor CO2 levels, we have to look back at our evolutionary history. For about 1 million years, during the entire evolution of Homo sapiens, atmospheric CO2 levels fluctuated within a narrow band of 180 to 280 parts per million (ppm). Our biology is finely tuned to this prehistoric atmosphere.

Contrast that with today. Due to industrialization, outdoor atmospheric CO2 now exceeds 400 ppm—a level “never experienced by Homo sapiens.” But the real change has occurred indoors, where modern humans spend the vast majority of their time. In Europe, for example, people now spend over 90% of their lives inside buildings and vehicles.

Indoor CO2 concentrations are always higher than outdoor levels due to human respiration. Typical indoor values range from:

- 600-800 ppm in well-ventilated offices and homes.

- Up to 4,000 ppm or higher in crowded, poorly ventilated environments like classrooms, meeting rooms, and cars.

When you synthesize these facts, an alarming picture emerges: for the first time in human history, our species is chronically exposed to carbon dioxide levels that are two, three, ten, or even fifteen times higher than the atmosphere in which our brains and bodies evolved. We are running a global, unprecedented experiment on the human brain, subjecting it to an atmosphere for which it was not designed—an atmosphere that, as the research in the previous section shows, directly impairs its function.

3. “Bad Air” Has a Number—And It’s Shockingly Common

The study on decision-making identified a clear threshold where our brains begin to suffer: 1,000 ppm. At this level, cognitive function was already significantly diminished. The alarming reality is that we routinely spend time in environments where CO2 levels far exceed this critical tipping point.

Consider these real-world examples documented in scientific surveys:

- Schools: In surveys of elementary school classrooms in California and Texas, average CO2 concentrations were greater than 1,000 ppm. A “substantial proportion exceeded 2,000 ppm,” and an astonishing 21% of Texas classrooms saw peak CO2 concentrations over 3,000 ppm.

- Meeting Rooms: In a study of office meeting rooms, where important decisions are often made, CO2 levels were found to reach up to 1,900 ppm during meetings.

- Vehicles: Modern cars are increasingly airtight. Based on ventilation data from a small study, researchers estimated that a car with just one occupant could see CO2 concentrations climb as high as 3,700 ppm above outdoor levels, with that number increasing with more passengers.

The very environments we have built to foster learning and critical thinking are often delivering an atmospheric composition that is not only historically unprecedented but is actively undermining those cognitive goals.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Air We Breathe

The evidence is mounting that the carbon dioxide in our stuffy rooms is far from harmless. Emerging science shows it directly impacts our ability to think clearly at levels we encounter every day. This challenge is compounded by the modern push for energy efficiency, which has led to more airtight, sealed buildings that often sacrifice ventilation. This is no longer an abstract question, but an urgent consideration for public health, urban planning, and the fundamental design of the spaces where we spend our lives. As we engineer our environments to be more efficient, are we inadvertently designing a future where we are less healthy and less intelligent? And what must we do to ensure our “fresh air” is truly fresh?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Jacobson, T.A., Kler, J.S., Hernke, M.T. et al. Direct human health risks of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nat Sustain 2, 691–701 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0323-1

Karnauskas, K. B., Miller, S. L., & Schapiro, A. C. (2020). Fossil fuel combustion is driving indoor CO2 toward levels harmful to human cognition. GeoHealth, 4, e2019GH000237. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GH000237

Satish, U., M. J. Mendell, K. Shekhar, T. Hotchi, D. Sullivan, S. Streufert, & W. J. Fisk. (2012). Is CO2 an indoor pollutant? Direct effects of low-to-moderate CO2 concentrations on human decision-making performance. Environmental health perspectives 120, no. 12, 1671.