This blog post and the “Deep Dive” and “Critique ” podcasts, created by NotebookLM, are based on “Emergence of an oceanic CO2 uptake hole under global warming” by Huiji Lee et al. (2025).

Deep Dive Podcast “North Atlantic Carbon Sink Reverses Near-Term” powered by NotebookLM:

Two hosts provide a critical analysis and constructive feedback to help readers to better understand the study in this NotebookLM-powered session: “CO2 Sink Hole Context and Framing”

Introduction: Our Ocean Ally Is Sending a Warning

The global ocean is a crucial ally in the fight against climate change. For decades, it has acted as a massive buffer, absorbing approximately 30% of all human-caused carbon dioxide emissions and slowing the pace of global warming.

What if a key part of this system, known for being one of the most efficient CO2 sponges on the planet, was about to reverse course?

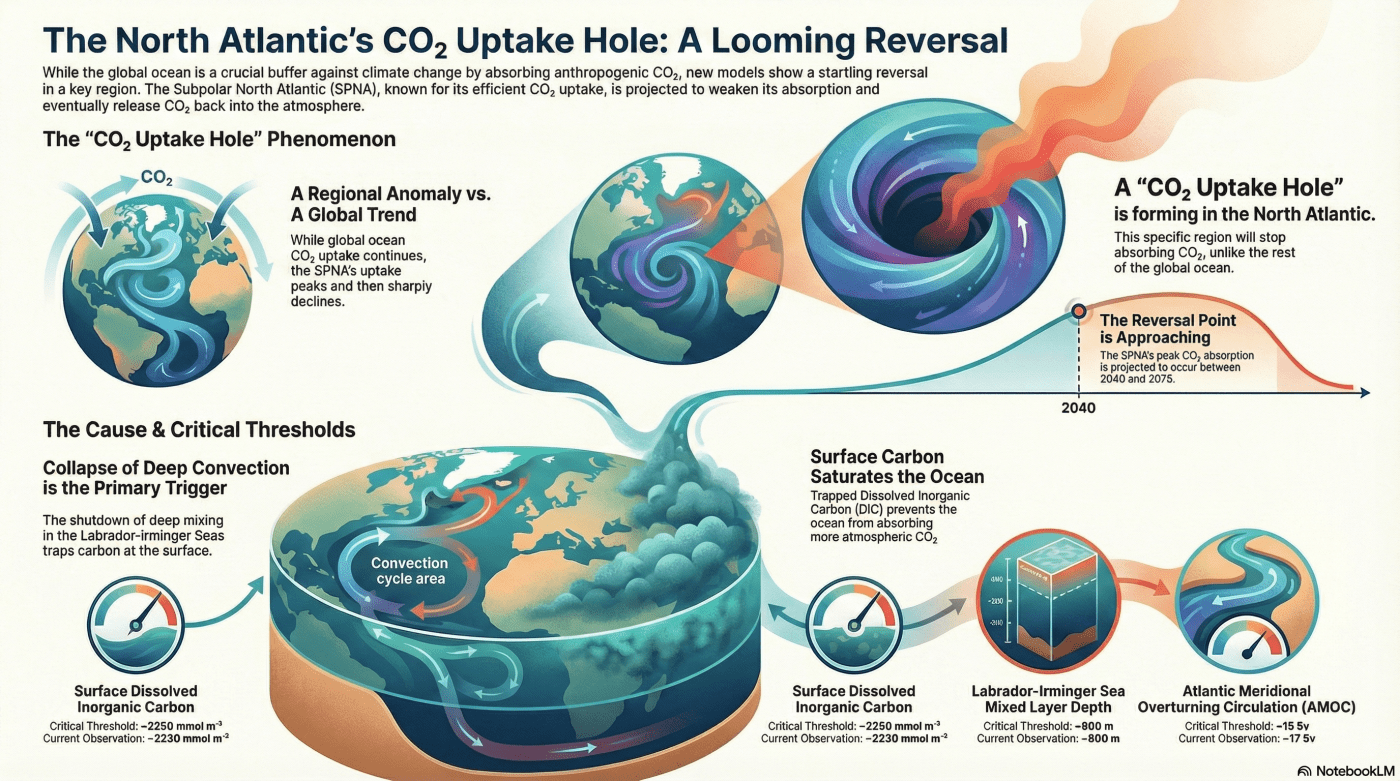

A startling new study published in Nature Communications by Dr. Huiji Lee and a team of researchers reveals a new phenomenon in the Subpolar North Atlantic. Computer models project a dramatic weakening—and eventual reversal—of the region’s ability to absorb carbon. The scientists have named it the “CO2 uptake hole.” This article will break down the most important takeaways from their discovery, a phenomenon they found not only in their own simulations but also confirmed across a suite of the world’s leading climate models (the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6).

1. The Shocking Reversal: A CO2 Sink Is Shutting Down

A powerhouse CO2 sink is predicted to stop absorbing carbon.

The Subpolar North Atlantic (SPNA) is disproportionately important to the global carbon cycle. While it covers only 15% of the world’s ocean area, it holds over 23% of the oceanic anthropogenic CO2, making it a highly effective carbon sink.

The study’s core finding is that this is set to change dramatically. Climate models predict that the SPNA will soon experience a pronounced weakening of its CO2 uptake. In this reversal, the concentration of CO2 in the ocean’s surface water begins to rise faster than the global average. Essentially, the ocean’s surface becomes so saturated with carbon that it loses its ability to draw more down from the atmosphere, much like a full sponge can’t absorb more water.

The researchers named this the “CO2 uptake hole,” drawing a direct analogy to the “North Atlantic warming hole”—a known phenomenon where this same ocean region has been cooling while the rest of the globe warms. Both “holes” represent unusual and counterintuitive regional responses to global climate change.

“Although the ocean usually plays an important role as a reservoir for absorbing anthropogenic CO2, the Subpolar North Atlantic weakens the ability to sequester CO2 much faster than other regions.”

2. The Real Culprit: It’s Not Just the AMOC

The cause is a collapse of local “deep convection.”

Discussions about major changes in the North Atlantic often focus on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the famous ocean “conveyor belt.” While a long-term weakening of the AMOC is a known factor that can reduce CO2 uptake, this study identifies a more direct and faster-acting culprit.

The research pinpoints the collapse of local deep convection in the Labrador and Irminger Seas as the primary trigger. In simple terms, this is a shutdown of the deep mixing of ocean water that characterizes the region. The study explains that this is ultimately linked to a weakening of the Subpolar Gyre (SPG) under global warming, which suppresses the deep mixing process. Normally, this vigorous mixing pulls carbon from the surface and sequesters it in the deep ocean.

When this deep mixing stops, Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC) builds up with alarming speed—what the researchers describe as “explosively”—in the upper 200 meters of the ocean. The surface water becomes saturated with carbon, physically preventing it from absorbing any more CO2 from the atmosphere. This surface-level saturation is the direct mechanism that creates the CO2 uptake hole.

3. An Alarming Timeline: This Could Happen Sooner Than We Think

The shift could begin within the next two decades.

The collapse of local deep convection is projected to happen on a much shorter time scale than the permanent, century-spanning collapse of the AMOC that is often discussed.

The study projects when CO2 absorption in the SPNA will hit its peak and then begin to sharply decline. According to the models, this critical shift is not a distant threat. Under the highest emission scenario (ER1.5), the models project that CO2 absorption will hit its peak and then begin to decline around the year 2040. The timing shifts under lower emissions:

- Under an intermediate scenario (ER1.0), this occurs around 2053.

- Under a lower scenario (ER0.5), it occurs around 2075.

This is not a far-off problem for future generations. The process represents a fundamental shift in the Earth’s carbon-regulating machinery, and it is projected to begin within the lifetime of many people alive today.

4. Measurable Warnings: Scientists Have Identified Tipping Points

There are clear thresholds we can monitor.

The study found that the system doesn’t just decline gradually—it can change abruptly once certain tipping points are crossed. By identifying these thresholds, the researchers have essentially outlined an early warning system. These are measurable metrics scientists can track to see how close we are to this critical shift.

The researchers identified three key indicators that signal the emergence of the CO2 uptake hole. When these thresholds are crossed, the reversal becomes much more likely.

- AMOC Strength: The larger circulation weakens to a strength of around 15 Sverdrups (Sv).

- Local Ocean Mixing: The Mixed Layer Depth in the Labrador-Irminger Seas—a measure of deep convection—shallows to about 200 meters, signaling a shutdown.

- Surface Carbon Concentration: The concentration of surface Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC) reaches a threshold of around 2200–2250 mmol m–3.

The study cautions that because these thresholds appear consistently across different models and emission scenarios, the emergence of the CO2 uptake hole “may be unavoidable.”

Conclusion: A Double-Edged Sword for the Future

The study’s findings deliver a stark warning: the Subpolar North Atlantic, one of our planet’s most vital carbon sinks, is projected to flip and potentially become a carbon source due to a rapid collapse in local deep ocean mixing.

Yet, the researchers point to a final, unexpected twist—what they call a “double-edged effect.” While the CO2 uptake hole is an alarming development for the natural carbon cycle, the very mechanism that causes it (the trapping of substances at the surface) could make the region more effective for certain human-led carbon dioxide removal strategies. For example, strategies like Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement (OAE)—a method that involves adding alkaline substances to seawater to boost its natural ability to lock away CO2—could be more efficient there, as the added alkalinity would remain concentrated at the surface instead of being lost to the deep ocean.

As we uncover these complex and unexpected feedback loops in our climate system, how must we adapt our strategies for mitigation and intervention in a world of growing uncertainty?

The infographic was generated by Notebook LM.

Lee, H., Noh, K.-M., Oh, J.-H., Park, S.-W., Shin, Y. & Kug, J.-S. Emergence of an oceanic CO2 uptake hole under global warming. Nature Communications 16, 3199 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57724-7

In this study, initial CO2 uptake rate is set to 0. But, the current estimate is -0.3 ~ -0.6 PgC/y of CO2 uptake in the NATL. Assuming a 1/3 of this happens in SPNA, the initial CO2 uptake rate should be about -0.1 ~ -0.2 PgC/y. So, it is unlikely that the actual outgassing occurs in this century.

@jaimepalter.bsky.social posted:

Something important to note: authors design their own (very high) Emissions Rates to explore this phenomenon. One rate mimics RCP8.5, which is widely considered to represent an unrealistic return to coal burning. They then multiply this rate by 1.5 (!) and 0.5. Even the 0.5 rate is worse than “current policy.” Nothing wrong with hitting the simulation with a big hammer to see what is possible, but the results should probably be interpreted through a lens of what’s possible, not likely.